Wynton Marsalis: Reclaiming the Jazz Tradition

Since his emergence as a leader in 1982, trumpeter Wynton Marsalis has been widely considered to have the most promise of any jazz musician of his generation. But in the tenth year of his solo career, as he approaches the age of 30, it is perhaps time to stop talking about Marsalis’s potential and start talking about his very real accomplishments.

In a sense, those accomplishments have not been neglected thus far. After all, Marsalis did win Grammys five years in a row for his jazz records (plus another three Grammys for his classical recordings) and was named Jazz Musician of the Year by the downbeat magazine Readers Poll for five consecutive years during the 1980s.

He has released a series of albums that have been critically and commercially well-received, and he has toured internationally.

A the same time, however, Marsalis has been a figure of controversy for his musical approach and his outspoken views, and in the interview he granted Goldmine recently, while discussing his career to date, he often found reason to dispute critical remarks made about his work and his approach to jazz.

It may be best, before delving into that discussion and those disputations, therefore, to try to briefly summarize Marsalis’s attitude toward jazz history, since it is one that, even now, does not necessarily conform to the majority opinion; and since it shapes much of the approach he has taken to his work.

Unlike those who wou see jazz history as a series of vaguely related but essentially discontinuous phases – New Orleans style, ragtime, swing, bebop, cool jazz, free jazz and fusion – Marsalis sees it as an evolving, consistent whole at least up to a certain point. That is, he believes that the melding of jazz with electric instruments and rock and funk styles to create fusion, a process that took place in the late ’60s and continues to these day, results in a music that not only is not very good, but that is not jazz at all.

As such, he perceives the era in which he grew up as a kind of dark ages in jazz history, a period when its thread was in danger of being lost, and he sees it as his mission to restore that continuity. In the course of the interview, this writer noted that Marsalis was making his career sound like “a reclamation project,” and he readily agreed with that description.

Marsalis has been enormously influential in propounding his views, not only onstage and in interviews, but also in his frequent visits to high schools and colleges around the country. But, of course, not everyone agrees with his position, and even among those who do, few go into the more technical aspects of the highly academic approach the trumpeter takes. In short, he has often felt misunderstood, and that comes across in his remarks below.

For this reason, it’s perhaps best to begin with a disclaimer Marsalis made late in the interview about what he thought of the press coverage he has received. “I don’t really have a problem with it,” he said. “I’m just commenting on it from my perspective. It’s not like I feel that I’ve been slighted, because I’ve been the most fortunate person in terms of the publicity that I’ve gotten. You go to figure the really great musicians, I go back and read what they were writing about them, the people who really could play. What they have done [to] me is not that bad.” As we shall see, however, Marsalis does not think it’s good either.

Wynton Marsalis was born in New Orleans on October 18, 1961, the second son of jazz pianist and educator Ellis Marsalis. He was given a trumpet from Al Hirt, but didn’t really begin to work on the instrument until he began studying classical music at 12. Prior to that time, he emphasized, it wasn’t possible for him to be exposed to jazz in the way the earlier musicians were.

“For musicians in our generation,” he said, “for us [as] we grew up, we didn’t play the blues and that all kind of stuff. We played funk and pop music. There’s a long distance between that and playing jazz. I mean long. And it takes a very conscientious desire to study and constantly work to learn how to swing. These things are learned things. It’s not natural to pick a trumpet and sound like Louis Armstrong. He learned how to play like King Oliver. My father knows thousands of standards songs. That’s what they played when he was growing up. He made love to women with that song, he met my mother when those songs were playing. We were listening to the Isley Brothers”.

Once Marsalis did begin to study, however, it wasn’t long before he began to gain notice in New Orleans as an up-and-coming jazz trumpet player. As related in the article on Lionel Hampton in this issue of Goldmine, he was drafted into playing with the veteran leader for a brief period in his teens only failing to go out on the road with him because of his youth. Marsalis chuckled at the memory. “I was playing with him on my prom night”, he said.

During his school years, Marsalis played first trumpet in the New Orleans Civic Orchestra. In 1979, when he was 17, Marsalis was admitted to the summer program at Tanglewood’s Berkshire Music Center, even tough its usual age requirement was 18. At 18, Marsalis entered the Juilliard music school in New York and he also found employment playing in the pit orchestra for the Broadways show Sweeeney Todd and with the Brooklyn Philharmonia.

In the summer of 1980 Marsalis accepted an offer from veteran jazz drummer Art Blakey to join his group, The Jazz Messengers, a band that served as school for promising young musicians. He gained great recognition with Blakey, and made a number of recordings under various titles and by various labels over the years, among them Live at Montreux and NorthSea (Timeless), Recorded Live at Bubba’s (Who’s Who), _The All American Hero (Toledo), Wynton Marsalis’ First Recordings (Kingdom Jazz), Wynton (Who’s Who In Jazz), Album of The Year (Timeless, also Impulse!), Straight Ahead (Concord), Keystone 3 and The Young Lyons (Elektra).

Despite of the praise he earned for his work with Blakey at the time, Marsalis in later years disparaged the state of his talent at the time. “I was just playing scales in whatever key my tune was in,” he told Stanley Crouch in a November 1987 interview in Downbeat. “That was enough to be considered musical in my era.”

Asked in 1991 if he still felt he was “just playing scales” with Blakey, Marsalis replied, “Yeah I think that and also the sound on recordings is not very good. The quality of sound really made a tragic decline in the 1970s. As far as what I was playing, it was not really informed with enough of the history. But coming out the generation that I come out of, it was in dialogue with that. So, it depends on what context it’s viewed in. If it’s divorced from the times, then it’s bad, but if it’s viewed in the context of what was going on, it’s good.”

In the summer of 1981, took a leave of absence from Blakey to go out on tour with Herbie Hancock. Hancock the jazz pianist who first gained wide recognition with Miles Davis, had later recreated a group with a similar sound to the Davis quintet of the ’60s – Davis on trumpet, Wayne Shorter on saxophone, Hancock on piano, Ron Carter on Bass and Tony Williams on drums – merely substituting Freddie Hubbard for Davis and calling the result V.S.O.P (“Very Special One-Time Performance”). Now, Hancock recruited Carter and Williams and added the 19-years-old Marsalis, for a tour as the Herbie Hancock Quartet.

Tnis only increased Marsalis’s exposure, as did the subsequent album Herbie Hancock Quartet (Columbia), and helped lead to a solo contract with Columbia as well as another album, Fathers And Sons, on which Marsalis was joined by his older brother Branford, his father, and members of Chico Freeman’s family.

Thus, before reaching the age of 20, Marsalis was embarked upon a career as a solo artist. Since critics such as Gary Giddins (as recently as the March 29, 1991, issue of Entertainment Weekly) have speculated on the possible negative impact of his “being a bandleader since practically the beginning of his career,” it seemed appropriate to ask Marsalis about taking on such a responsibility and how he decided he was ready.

“That’s a hard transition,” he said of the move from band member to bandleader. “For me, it wasn’t so much a matter of being ready. It was that I had something to do, and I was sent to do that. That’s what Art Blakey prepared me to do, and the scene was much different at that time than it had been in the past. So, it required that I step up and do things that perhaps at an earlier time I would not have had to do, because I had to articulate a conception for my generation, and I could only do that under the banner of my own conception.”

So, in a sense, Marsalis felt he had a responsibility that was beyond merely the furthering of his career, but was also, he said, “in terms of articulating what we were going to do in terms of addressing jazz music because then – if you remember then-the question was, were people even playing jazz? Because everybody was pretty much playing this instrumental pop music they were calling jazz. So, for me, at that time, I had to articulate a vision of what it would be for my generation.” Although Columbia Records is seen a’s championing the approach Marsalis took, to the point of being accused of hype, Marsalis said he did not receive initial support from the label in the direction he wanted to go.

“They didn’t want me to record jazz, of course,” he said. “They wanted pop music, like everything else. I was fortunate to have the publicist I had, Marilyn Laverty. She sold my record, pretty much. The record company wasn’t enthused about it. They wanted me to be the answer to Tom Browne. [Author’s note: Tom Browne is a jazz trumpeter who scored the Top 5 Soul hits “Funkin’ For Jamaica (N.Y.)” and “Thighs High (Grip Your Hips-And Move”) in 1980-81. There are many things that are said now that are not true about jazz. ‘We wanted jazz.’ They didn’t, and I had to fight every step of the way for the “first five or six years of my career with them. I was fortunate that I had tremendous support from the jazz critics. And from the fans. And the musicians.

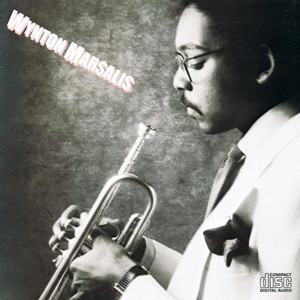

Marsalis’s debut album, Wynton Marsalis, was released in January 1982. The album was produced by Hancock, and some of its tracks had been recorded in Japan with the Hancock Quartet, while others featured members of the new quintet Marsalis was putting together, a band that featured his brother Branford on saxophone, Kenny Kirkland on piano, Jeff Watts on drums and Clarence Seay or Charles Fambrough on bass.

The album was a commercial success, even breaking into the pop charts in March, where it peaked at #165 during a five-week run. Perhaps predictably, given its youth, his appearance (Marsalis adopted the suit-and-tie image common to jazz musicians until the mid-1960s) and his traditional, acoustic approach to jazz, he was frequently compared to jazz musicians of the ’50s and ’60s. Even as late as 1991, Gary Giddins, in talking about Marsalis at the start of his career, spoke of “the ghostly influence of Miles Davis, wiih whom Marsalis was endlessly compared in the ’80s, not without justification.”

Marsalis himself rejects such comparisons, not surprisingly. As to his ability to emerge from his influences into his own voice, he said, “The question of individuality and originality and greatness is, how many personalities can you absorb and still be yourself? Great artists like Beethoven, Bach, Picasso, Duke Ellington, they proved that over and over again. How many styles can you absorb and still be yourself? And in terms of our music, I felt that it always sounded like it. A lot of things were written or said, but I don’t think the music really bears that out.”

Some said, for example, that Marsalis, was trying to recreate previous styles. whereas he felt he was trying to reclaim a tradition. “Erroneously, those who have written about it said we are trying to recreate the past, which is not what we’re trying to do, because that’s impossible,” he said. “What we’re trying to do is address the sophistication of the past. And the fac1 that we always have sounded like ourselves, that’s undeniable. Even the first record, I know that it’s me playing. It doesn’t sound like anybody else. I wish it did sound like somebody else a lot of times!

“One thing I’d like to say about the opinions, I don’t really mind that, it doesn’t disturb me. I think that it’s good to have a dialogue about what you’re doing, and it can’t all be positive, and it’s necessary to have those who will critique something and say that it’s something or something else. The only tragedy with jazz criticism a lot of times is that it’s not based on any real understanding of the criteria of jazz, like what makes a jazz performance successful. It’s generally-based on social science surveys or some other cliched way of thinking. But I really don’t have a problem with criticism at all. I think it’s healthy for stuff to be criticized.”

Marsalis was asked to describe his own intentions on his debut album. “I had a concept, and I was just trying to present it,” he said. “I had one tune that was a blues, another that was rhythm changes using a call-and-response between me and my brother. On the blues tune, it had a groove on it and some interludes and modulations in a different key. I had another song that went in a different time, it had a contrapuntal type of call-and-response with the horns. Another song that was a standard and some other songs that were originals. So, J was trying to address a comprehensive, a wide range of music inside of the jazz tradition. And I also wanted to declare definitely that I was going to play jazz.”

The declaration was certainly understood, as Marsalis won the first of his five downbeat awards for Jazz Musician of the Year at the end of 1982 and was nominated for a Grammy for title Wynton Marsalis LP in early 1983.

This was only a curtain raiser on the recognition Marsalis received in June 1983 with the simultaneous releases of his first classical album, Hummel/Haydn/L. Mozart Trumpet Concertos and his second jazz album, Think Of One…

The classical album entered the classical charts in August, spending four weeks at #1. Think Of One… , meanwhile, hit #2 on the jazz chart and got to # 102 in the pop chart. At the Grammy award ceremonies in early 1984, Marsalis became the first artist to win back-to-back awards in the jazz and classical categories.

The trumpeter downplays the broad success that resulted. “You never know why something is recognized or not recognized, and that’s not really a barometer of the success of any of the albums, to me,” he said. “The success of the album is just in the documentation of the ideas. If that’s done, and it’s an accurate documentation, then I feel that it’s successful. All of the albums are like that”.

And what was Think Of One. .. intended to document? I was just trying to extend some of the things I was working on on the first album,” Marsalis said. “Some originals, I have a blues on it again and another concept type tune featuring a lot of group interplay. Another song called ‘The Bell Ringer’ that uses a groove and a standard on it called ‘My Ideal’. A tune written by (bassist) Ray Drummond, ‘What Is Happening Here (Now)?’ with some chord changes on it and ‘Think Of One,’ an arrangement of a Monk song using stop time. I was trying to feature mainly a group concept more than a solo album.

“Most of my albums have a real conception for the band and a concept for the album, and I’m most excited about a group conception and a total musical conception. So, I’m always trying to document a wide range of feelings in jazz and moods and different tempos and also create music that allows the guys in my band to have room to play and really express their personalities.”

Along with Marsalis himself, Branford Marsalis was gaining recognition through the group’s recordings and performances, and the older brother launched his own solo career, while still, for the moment, playing in the quintet, with his LP Scenes In The City in the spring of 1984. (Miles Davis, in his autobiography, notes that he tried to hire Branford, who had played on his Decoy album, for his own band during this period.)

On May 30 and 31, 1984, Wynton Marsalis recorded his third jazz album, Hot House Flowers, at RCA Studio A in New York, using his quintet (the always-changing bass chair being occupied for the occasion by Ron Carter) and string arrangements and featuring such standards as “Stardust” and “When You Wish Upon A Star.” When the result was released in September, along with a second classical album, Wynton Marsalis Plays Handel. Purcell, Torelli, Fasch, Molter, Marsalis was on his way to adding two more Grammys to his collection. (There had also been a classical trio album, Haydn: Three Favorite Concertos, recorded with Yo-Yo Ma and Cho-Jiang Lin, released in May 1984). Hot House Flowers spent 21 weeks on top of the jazz chart and broke into the Top 100, reaching #90. The classical album hit #4 on the classical chart.

Heard today, Hot House Flowers, with its familiar material, sounds like a precursor to the three Standard Time albums Marsalis made from 1986 to 1990_“Rigbt,” he said. “For me, the question, then, in the early ’80s, was to deal with the whole transition from pop levels of emotion to adult levels of emotion and jazz emotion, which is very different, and it’s always been a struggle to address that, coming from my generation.”

Did he mean, he was asked, that he was trying to recruit people to his musical approach? “No,” he said, “I’m just trying to come up with a documentation of some music that will stand up against the history of the music. Because I was raised in a time which was a down period in terms of our musical culture, it means that I have to work harder to address basic and fundamental elements. Things that perhaps could have been taken for granted, when the popular music was written by people like Gershwin and Cole Porter, I couldn’t take for granted. So, there was a lot of intellectual work that had to be done.”

The Marsalis Quintet (with regular bassist Charnett Moffett on most tracks) returned to the studio in January 1985 to cut Black Codes (From The Underground), which was released the following September, resulting in another appearance in the pop chart (# 118), and two more Grammy awards.

“The group had developed more,” Marsalis noted, “and a lot of the songs used the same themes, and then I was trying to write more like a suite, using different conceptions and different grooves, and addressing the sophistication of different moods and using the whole album like a form, also constantly addressing the romantic aspects of the music and trying to develop (a) certain understanding of the sensuality of the music without sinking down into cliched ways of doing things. And also playing in different keys and the same aspects of the music, call-and-response and group interplay, using groove, playing blues, like the song ‘Black Codes’ is a big extended blues.”

Once again, Marsalis felt compelled to talk about the lack of understanding of his work in the press at the time of the album’s release. “In terms of what I’m dealing with, of a real level of improvisational complexity, (of) course, it hasn’t been analyzed or dealt with or discussed seriously,” he said. “I think that’s one thing all of my music has in common. I’ve never really seen any serious discussion of it on anything but the most trivial level. Most of the analysis of it is never really accurate. I don’t think there’s any attempt to analyze it or deal with it, really.”

His interviewer pointed out that, at least in the broader parts of the mass media, an analysis like the one he sought might be considered too technical for a general readership. He disagreed. “I don’t mean necessarily technically,” he said. “I mean just a description of what the music actually is in terms of the type of call-and-response we’re trying to play, in terms of the different moods, the tune-set-up, how the tunes come out of the fusion era and they try to address jazz music. There’s never any serious discussion of it. Like, let’s say, a song like ‘Black Codes (From The Underground).’ You wouldn’t have to have a technical understanding of music.

The main theme, the bass theme, comes from a tune by the Meters called ‘Hey Pocky Way,’ and it uses a New Orleans type of groove, and this is before I had (New Orleans natives) Herlin (Riley) and Reginald (Veal) in the band. Then we go to a certain type of swing that’s an extended blues form. Then it goes back to the New Orleans groove that has a soprano solo on it. Then it modulates in another key.

“But, you know,” Marsalis continued, “the music is just never addressed seriously. It’s always just some cryptic reference to somebody else’s music: ‘Oh, this is like Mingus,’ or ‘this is like Miles,’ or ‘this is like ‘Trane,’ you know what I mean? Just some real strange – it just always amazes me that my music is never addressed as what it is. It’s generally just reduced to being like something else, and when the articles on me are written, it’s generally just some discussion about whether I fired my brother or not, or what happened with me and Miles.

“Now it’s about young musicians that I’ve recruited to play, and even that, now, sometimes that gets reduced to imagery. Like this thing about the image of me being in records. It wasn’t an image that forced me to get up at seven and eight o’clock in the morning all them mornings to go to them high schools all over the country for all those years. It’s always an attempt to reduce whatever the achievement is to some formula.”

At the risk of raising Marsalis’s ire, it can be pointed out that, during the ’80s, he sometimes reacted to the comparisons between himself and Miles Davis, and to the differences in current musical style between the two, by saying things that Davis, at least, interpreted as criticisms. In his autobiography, Davis blames Columbia Records’ attentions to Marsalis as one of the reasons he left the label in 1985, and he describes an incident in 1986 at a concert, during which Marsalis turned up onstage unexpectedly and was not at all welcomed by Davis.

Perhaps more serious to the progress of Marsalis’s career was the departure of bis brother Branford and pianist Kenny Kirkland in 1985, when the two joined a band put together by the rock star Sting. When asked about the positive aspects of shifting personnel in a band to get a fresh approach, Marsalis pointedly replied, “I didn’t want the personnel to change. The guys in the band left to go play with Sting. So, I had to get other members, and then (pianist) Marcus Roberts came into the band and my brother wasn’t playing with us.”

Marsalis had also added bassist Robert Hurst, resulting in a quartet with himself, drummer Watts and Roberts that recorded his next jazz album, J. Mood, in December 1985, released in September 1986. (Another classical album, Tomasi/Jolivet: Trumpet Concertos, was released in January 1986).

Since Marsalis had previously noted that he wrote with specific musicians in mind, he was asked whether the change in his band resulted in a fundamental change in his musical approach. “Oh, yeah, definitely,” he ,said. “You can tell, there’s a big difference in the sound of ihat record.”

Asked to describe J Mood, he replied, “It’s a blues, the title track, too. A slow blues, a minor blues, and it uses the same elements we had been using since the first album, go modulating into different times, using the call-and-response, the group interplay. Now it’s even more developed and refined. Trying to address different moods and grooves, like in tunes like ‘Melodique’ and ‘After’ and ‘Presence That Lament Brings’ and playing with the time a lot and playing original compositions that have challenging chord changes, like the song that Donald Brown wrote, ‘Insane Asylum’, and the song I wrote called ‘Skain’s Domain’ that uses a lot of different time signatures, and the type of complex harmonic language and melodic language we had been working out.

“[Much] Later’ is also a blues in which we deal with the group call-and-response, and then also trying to address swing and further our understanding of the music. Also we’ve been trying all along to get better sound on the records. So, that record, we made kind of a leap forward, but still we were struggling with the actual sound on the album.”

Marsalis had turned to digital recording for Hot House Flowers, and continued to refine his recording techniques since. He was asked what made J Mood a special development in this regard. “A lot of it was the way we used the technology, and also the way we were playing ourselves,” he said. “Since we grew up always playing on monitors and everything real loud, it was very hard for us to develop sounds and learn how to play softly so it would record well, but with a a lot of intensity so it would still have the power.”

The power was felt by record buyers, who pushed J Mood into the pop charts and the Top 1O of the jazz charts, by the readers of downbeat, who awarded Marsalis his fifth straight Jazz Musician of the Year award at the end of 1986, and by the Grammy voters, who gave Marsalis his seventh Grammy for the album in February 1987.

By’ then, Marsalis had finished recording three new albums. His next classical release, Carnaval was released the month of the Grammy ceremony. His next jazz album, Marsalis Standard Time, Volume 1, had been recorded in sessions in May and September 1986, but was not released until August 1987. (It would be the first of three volumes in Marsalis’s series of resettings of well-known compositions.)

“They all had very different conceptions,” he says of the Standard Time albums. “The first one was dealing with a lot of metric modulations and time changes and still trying to develop the whole adult conception of romance, and playing in different tempos and times, just really learning how to deal with that harmonic vocabulary. Once again, the sophistication of that had largely been lost on our generation in terms of applying the blues and the harmonic knowledge to that material.

In December 1986, the Marsalis Quartet had recorded a live double album at the Blues Alley Club in Washington, D.C., though its release was held back for a year and a half. “I had always regretted that I didn’t get a good live recording of the band that I had with Branford and Kenny and Charnett and Jeff,” Marsalis noted, “because we used to play a lot better live than we played on the record. We used to play with a lot of energy. So then the quartet recorded a live record, – and that record, we were trying to really play with a lot of meters and time changes and stuff that we were doing at that time, and that recording is shaped more like a suite, too, because it has a lot of interludes and stuff in it.”

“Knozz-Moe-King”, the lead-off track from Think of One… , serves as a touchstone throughout the recording. “Right,” said Marsalis. for the basis of the improvisation, and that [album], it’s more documentation.”

The 1987 release of Marsalis Standard Time, Volume I and Carnaval resulted in more popular successes for Marsalis and more Grammy nominations. In February 1988, he won his eighth Grammy for “Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Group,” his fifth straight jazz Grammy. Marsalis was unable to be on hand on Grammy night, but sent the following message: “My tour of Australia prevented me from accepting this award in person. This is particularly special. Receiving eight consecutive awards in five years is an affirmation to me, and hopefully a signal to others that both NARAS (the National Academy of Recording Ans and Sciences, which awards the Grammys) and my peers have a sincere appreciation of quality in American music, and that it is not necessary to use gutter language, sexual innuendoes, and other trendy gimmicks designed to exploit the immaturity of adolescents to be a successful recording artist. It is with great pride that I accept this Grammy award.”

The controversy over pop music lyrics had begun a few years earlier and would reach something of a peak a couple of years later (when Marsalis’s views would be detailed by his manager, Edward C. Arrendell II, in an editorial in Billboard magazine), but his salvo at the Grammys seemed particularly heartfelt, especially coming from a musician who spends so much time visiting schools. He was asked to elaborate on his views.

“For me, it’s not the lyrics, it’s the music,” he said. “Music is more powerful than lyrics, and when you study music from all over the world, there are many thousands of grooves. I can’t understand why every song has to have something slapping down on two and four on it. That’s what I’m averse to. I mean, why is that necessary, for every song to be the same beat? The lyrics, that’s whatever it is, if you have that beat going on, it really doesn’t make a difference what you talk about because the beat is what the issue is with the music.”

Yet Marsalis’s Grammy remarks referred specifically to language. Was he suggesting that records be stickered or that other restrictive legislation be enacted? “I don’t think there’s nothing you really can do about it, to be honest about it with you,” be replied, “and my personal opinion about those people is they shouldn’t be stopped from doing it, if that’s what they want to do. It’s just we should try to educate our young people so that these are not viewed as cultural achievements.

“See, I don’t have a problem with any of them people. If they want to curse and talk about dicks and pussies on albums: man, that’s their business. But don’t come to me with this and tell me that this is a statement of how people feel in the ghetto and all this other shit that they’re talking about. That’s just bullshit, basically. Or ‘it’s indicative of the black lifestyle,’ and all these other negative terms. Why does it have to be that? Why can’t it just be some people talking about dicks and pussies? I mean, people have been talking about that for centuries.

“All I’m saying is, view it for what it is, and once that’s done, it’s demystified,” he continued. “Then it’s not considered an achievement. Like, to grab your dick on television, I can’t understand why that’s such a big deal, or why a person 21 years old or 19 feels they have to do [that] to express sexual freedom. Why can’t that freedom lie expressed in the ability to come up with something that’s ascending, that addresses something of real true romantic substance and value? Freedom is an ascending proposition. Whenever you learn something, you’re trying to be free.”

Marsalis was asked about his personal observation of students’ expression of freedom through vulgar language. “They believe in that ‘cause that’s all they’ve grown up with,” he said. “They don’t know anything different from that,” and they truly, whole-heartedly believe in it. Whatever’s in the media, generally students will believe in. High school students, mainly. Whatever they see on MTV or whatever is written in these little magazines they read, because there’s not enough defense for them instilled by adults to at least give them an alternative.

“But when you give kids an alternative, generally they’ll choose the alternative. It’s like giving somebody the choice between a Rolls Royce or a Vega. They ain’t gonna take the Vega. Now, if you give them the choice between walking or the Vega, they’ll take that Vega any day of the week!

“It’s a long battle, but it will be won by people who believe in things that are ascendant. I firmly believe in things that are ascendant. I firmly believe that, because that’s just the nature of humankind. People always will choose what they know to be best. The question is, how can you get knowledge of the best out to the most people?”

At the time of his Grammy triumph in 1988, CBS released Marsalis’s next classical album, Baroque Music For Trumpets, which, except for a compilation, Portrait Of Wynton Marsalis, released the following September, is his most recent classical release. It spent 22 weeks on top of the classical charts, starting in April.

The Live At Blues Alley album finally came out in June 1988, the same month that Marsalis made two appearances at New York’s NC Jazz Festival, once as part of an all-star tribute to Louis Armstrong, and again with his group, in which Reginald Veal (bass) and Herlin Riley (drums) now made up the rhythm section, and which was now augmented by saxophonist Todd Williams. By September, when he played a week at New York’s Village Vanguard, Marsalis had brought the group up to sextet strength, adding another saxophonist, Wess Anderson.

In late October, the sextet, along with several added musicians, recorded music that would appear on an album called The Majesty Of The Blues in June 1989. The album was an ambitious one, mixing an unusually large number of horns, as its personnel implies, and featuring extended compositions, among them “The New Orleans Function,” which took up the entire second side of the record and featured a “Sermon,” “Premature Autopsies,” written by Stanley Crouch (who has contributed liner notes to all of Marsalis’s jazz albums).

+

The LP represented a strikingly different musical approach, and, if released material means anything, seemed to mark the first time the trumpeter had been in a recording studio in two years. But that wasn’t true. Why did The Majesty Of The Blues sound so different?

“Well, that’s because there are three records in between that that didn’t come out, and they’re coming out this July,” Marsalis said. “They’re going to be put out all at one time. The first is entitled Thick In The South and that was recorded in ’87, and it’s when I started to really concentrate on playing blues all the time, and all of those tunes are blueses, and it has Joe Henderson and Elvin Jones on it. Elvin is on two tunes.

“Then there’s another one called Uptown Ruler, and that’s actually the first record that leads to The Majesty Of The Blues. That’s when I first got Herlin Riley in the band, he and Reginald Veal. Now that made a big difference in the band in terms of the type of music and the style and the sound that we were playing, whereas, when The Majesty Of The Blues came out, most of what was written about it said, ‘Oh, he’s doing something really different, going back to New Orleans.’

“But the whole band was different. Now I had Todd Williams, who is a very serious young musician and exerted a positive influence on the band. Reginald Veal is on the bass and he’s from New Orleans, and Herlin Riley, who is also from New Orleans, is on the drums, and they both play with a totally different approach than Jeff Watts and Bob Hurst were playing with. So, the music had to change because the musicians were totally different. The only musician that was still with us was Marcus [Roberts].

“So the Uptown Ruler album, that’s the first album that’a kind of like The Majesty Of The Blues because it deals not just with the four-four, like swing groove, and it deals with a certain organic relationship in terms of the groove, the bass and the drums, and Uptown Ruler is in the form of a suite. The songs are somewhat related, and it has a different mood to it. The third record is entitled Levee Low Moan, and that record actually was recorded at the same time that Majesty Of The Blues was recorded, and The Majesty Of The Blues actually was supposed to be two records.

“But since the double record from Blues Alley bad just come out, CBS didn’t want to release two double records in a row ‘cause they said that they don’t sell. But I wanted tu put two records out, and I had already skipped over two records, Thick In The South and Uptown Ruler, which weren’t going to come out. So then I said, ok, just put The Majesty Of The Blues out, that one record. So, see, had both of the records come out, then that sermon in ‘The New Orleans Function,’ it wouldn’t have seemed as much as – ‘cause it’s not supposed to be a half of one record, it’s supposed to be a fourth of two records.”

Marsalis was asked about how he went about recruiting the new members for the band in 1988. “I was fortunate to get Wess Anderson in the band,” he said, “and a lot of times it was a matter of me waiting for musicians in my generation to play with that I really thought would want to deal with my music a certain way. It’s been hard. I had to wait for a lot of guys since they were in high school, like Todd. I knew him when he was 16, so I had to wait four or live years. He’s 20 on Uptown Ruler and Wess, yeah, I had to wait for the cat…

It was pointed out that Marsalis had talked about every album from this period except the one that actually did come out at the time. What had he intended with The Majesty Of The Blues? “The conception on The Majesty Of The Blues was from the most futuristic conception to the earliest, which is the song ‘The Majesty Of The Blues,’” he said. “There’s nothing in jazz that sounds anything like that. So I put that out, that’s the first song on that album, and then ‘The New Orleans Function,’ that goes back to the beginnings of music. So it was just a statement of continuity, which was missed.

“The whole thing that was commented on was, ‘playing New Orleans music.’ Now every time I play a show, they say, ‘He plays New Orleans music.’ I don’t think they’re really doing it to mess with me. I don’t feel like it’s a negative thing. It’s just, I don’t understand why it’s just difficult, I guess, to comment on the full range of what we’re trying to present, instead of just jumping on this one thing.”

In November 1998 Marsalis’s first film scoring assignment. the “Wright Brothers At Kitty Hawk” segment of the animated miniseries _This Is America, Charlie Brown!, was broadcast on CBS-TV. The following June, Marsalis continued his association with Charles Schultz’s comic characters, hosting a “Coolin’ It With Snoopy” matinee concert at Town Hall in New York as pan of the JVC Jazz Festival.

As part of Marsalis’s commitment to youth and education, the show was aimed at a young audience and featured 13-year-old saxophonist Amani A.W. Murray. Marsalis had also become the artistic director of Classical Jazz at Lincoln Center, and planned various programs for it, among them a three night Christmas series beginning December 20, 1989, and ending with a live national television broadcast from Alice Tully Hall over PBS. His band was now an expanded unit, adding a third saxophonist, Joe Temperley, clarinetist Alvin Batiste and trombonist Wycliff Gordon. (The previous September, Marsalis had released his own seasonal album, Crescent City Christmas Card).

Marsalis maintained his usual busy schedule in 1990, including his annual stop at the JVC Jazz Festival in June, when he appeared on a bill with Pearl Bailey in what turned out to be the singer’s last major appearance. The same month, Marsalis released his tenth Columbia jazz album, Standard Time Vol. 3 – The Resolution Of Romance, which featured a quartet of himself, his father on piano, and the rhythm section of Veal and Riley. (Note that the release of Vol. 3 preceded the release of Vol. 2).

“Three was just with my father,” Marsalis said, “and we were just mainly trying lo play ballads and just play pretty melodies, more than the group improvisation. We were featuring just the color and the timbre and the sound of different songs. We played in all the keys, and I was using a lot of different mutes, and also just to get a good documentation of my father’s sound and the type of touch he’s playing and Reginald Veal and Herlin Riley from New Orleans.”

November 1990 saw the release of Tune In Tomorrow …, Marsalis’s first soundtrack to be issued. The recording afforded Marsalis the opportunity to feature his larger unit, plus added guest musicians, including vocalists Johnny Adams and Shirley Horn. Different composers respond positively or negatively to the special pressures of soundtrack work, so Marsalis was asked how he found the experience.

“I enjoyed it, I liked it,” he said. “Well, I like pulling music in any context. I also have two other soundtrack albums, too, that are in the can, the one for Charlie Brown, and another one for a TV show called Shannon’s Deal.’ I really liked doing Tune In Tomorrow … ‘cause it had an orchestral score, too, that segued in and out of the jazz score. but it wasn’t in the final movie like the way it was written.

“Plus it gave me a chance to deal more with Duke Ellington’s music. A lot of the stuff off that soundtrack is based on themes and stuff that I heard on ‘The New Orleans Suite’, a composition by Duke, and, you know, whenever you get a chance to address something great in the music, it’s always fun.”

By December 1990, Marsalis was touring with a sextet. He opened the new year with a week-long stand at the Blue Note in New York. In March, Columbia released Standard Time Vol. 2 – Intimacy Calling, a record of 11 standards and one Marsalis original recorded from September 1987 to August 1990. “On the second one, we were just playing traditional standards.” Marsalis said. ‘There was really no concept behind it. It’s one of the few records I’ve done where I just put together a lot of different songs and moods. The band was different on that one, and we’re still dealing with the same type of group interplay, trying to play with more sophistication and more -just address the language of jazz. And also the language, the vocabulary of things that we had been working on since we started playing in the early ’80s, like our type of group interaction, our type of dealing with the blues, our type of approach to the time and the harmony.”

In May 1991, Marsalis toured in Japan and Mexico, and at the time of his Goldmine interview, was preparing 10 hit the U.S. jazz festival circuit for the summer and to record a new album in July. Over the nearly 10 years of his solo career, Marsalis has had a powerful effect on the way jazz is seen, both in terms of its anistic direction and its position as a part of American and world culture. He may not have brought the world around to his way of thinking entirely, but it’s not too much to say that he has helped to set the terms of discussion, helped to write the agenda.

He has also exerted a strong influence on other young musicians and on record companies which are newly willing 10 sign traditional jazz-leaning newcomers. One need only look over a crop that includes Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison, Marlon Jordan, Roy Hargrove, Joey DeFrancesco, the Harper Brothers, Harry Connick. Jr., Christopher Hollyday and a host of others – all young, all conservatively dressed, all interested in playing traditional acoustic jazz – to see that Marsalis, who 10 years ago stood alone in his approach – isn’t alone anymore. As such, he must be counted, if for no other reason, the major jazz figure of the ’80s, and still reigning at the start of the ’90s.

Of course, he doesn’t see himself as part of, or even the leader of, any kind of movement. Just ask. “I don’t like that at all “ he said. “This whole thing about a movement and all this shit. Ain’t no movement, it’s just individual musicians who want to play. All of the guys are trying to do something totally different, and they’re all on different levels of seriousness about music.”

by William Ruhlmann

Source: Goldmine