Wynton Marsalis, the sage of jazz

As Jazz at Lincoln Center moves into its new digs _ three theaters in the Time Warner Center on Columbus Circle _ Wynton Marsalis, its trumpet-playing star and artistic director, is behaving in an increasingly statesmanlike manner.

Sixteen years ago, when he fought for the organization to be taken seriously, his forceful pronouncements about the jazz tradition nearly split its fan base in half. Some sided with his view that jazz had lost its core identity, diluted by rock, funk, electronics and abstraction, and that it needed stern corrective measures before it could grow. Others saw Marsalis as a purist scold who wished to write all the innovations since the mid 1960s out of jazz’s official history.

Now, with Jazz at Lincoln Center the most powerful nonprofit jazz institution in the world, with a responsibility to its donors for the $128-million it took to build the halls, Marsalis’ declarations, and his answers to criticism, have become temperate and more like coalition-building.

“John Lewis said that even to complain about what somebody has done to you is a form of egotism,” Marsalis said recently in an interview in Manhattan, referring to the pianist of the Modern Jazz Quartet, one of many jazz heroes _ Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey, Elvin Jones _ who have counseled him since he was a teenager.

Marsalis started playing gigs when he was 12 and says he has never lost faith in himself. “Not only have I never lost it,” he said, “it has never been shaken.”

These days Marsalis, 43, enjoys a kind of attention that has little precedent in jazz, and so does Jazz at Lincoln Center. It has 3,500 subscriptions, which are expected to bring in $1.5-million this season. During Marsalis’ stewardship, the institution has gone beyond its initial goals _ creating a canon for jazz history and giving the genre more dignity _ to make it as respected by the public as classical music is. Now the arts complex appears to be more focused on expanding jazz into other disciplines _ dance, opera, drama _ and exposing jazz to the world through its educational resources.

As a musician, an ideologue and an arts administrator, Marsalis has created jobs and an official spot for jazz in New York where there was none, with the cooperation of the city, which gave $30-million to the new complex.

He also may be the most recognizable jazz musician in the street, the only one to win a Pulitzer Prize, in 1997, and one of the few who can easily sell out a midsize theater in this country and abroad.

Yet, as Marsalis has flourished in the realm of plush-theater culture, luxury-goods sponsorships, official ceremonies, television specials and books of reminiscence and advice, his ground-level influence as a bandleader in the jazz scene has declined.

His transformation is akin to that of a stunningly talented ballplayer who takes a job in the team’s front office. Musicians do not talk about his work nearly as much as they did 20 years ago. The question of whether Marsalis has been good for jazz has become an institutional one more than an aesthetic one.

“Jazz is not merely music,” is how he put it in a recent statement drafted for the opening of the new halls. “Jazz is America _ relationships, communication and negotiations.” When he pops up as a sideman, he becomes news on the grapevine. In many ways he has become an entity above and around the daily jazz world, yet not quite in it: “a bookkeeper, keeping the history present,” as trumpeter Leron Thomas put it.

Marsalis is competitively interested in setting an example and plays constantly. He performed so much over the summer, at festival dates in Europe and Canada and after-concert jam sessions at hotels, that his lip became inflamed. He canceled a performance in June at the Montreal Jazz Festival, minutes before it started. “I never had physical problems with my chops before,” he said. “And I never canceled a gig before.” His doctor told him to take a month’s rest from the horn.

He had enough to keep him busy: composing a commissioned piece, Suite for Human Nature, with a libretto by lyricist Diane Charlotte Lampert, for December; rehearsing with the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra; finishing a new book; and editing two new records. “With my life in general, I just keep going,” he said.

He moved to New York in 1979 to enter Juilliard after graduating from high school and was immediately recognized around the jazz scene as a virtuoso.

“I can’t think of any other musician at all who had that kind of buzz when he came to town,” said trumpeter Steven Bernstein, who arrived in New York the same week.

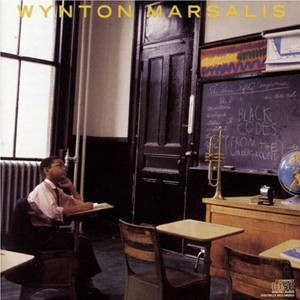

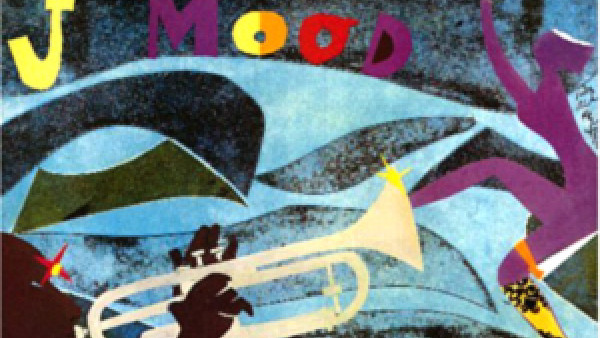

The buzz about Marsalis’ virtuosity continued for nearly a decade: through his tenure with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, the establishment of his own quartet, his output on Columbia Records and albums such as Black Codes From the Underground and J Mood, which jazz musicians paid close attention to in the mid 1980s.

By 1988, his role in jazz began to change, as did his music. It was the year he helped formulate a series of concerts at Lincoln Center, then called “Classical Jazz.” In his own work he reached back further, to the blues and Duke Ellington and the New Orleans ritual of the funeral parade, to create longer and more complex forms. He began playing more slowly, and his pronouncements about jazz and culture became broader and more trenchant. He was raising the stakes.

That year he also wrote an article for the New York Times headlined “What Jazz Is _ and Isn’t.” Marsalis argued for a hierarchy of talent. He held that critics and audiences had adopted a destructive openness that had led to a fundamental misunderstanding of jazz. He named rock, new-age music, pop and “third-stream” fusions of jazz and classical as weakening agents. “There may be much that is good in all of them,” Marsalis wrote, “but they aren’t jazz.” He contended that nothing new would be created without a knowledge of what was old.

His pronouncements engendered a bitter debate about his intentions: Did Marsalis want to help the music or own it? Did he sufficiently respect the last 40 years of jazz?

Today, Marsalis rarely issues outright challenges, and the concert programming of Jazz at Lincoln Center, the most controversial part of an organization that does many things, has broadened. He has explored the music of Cuba, Brazil and Argentina, presenting programs that venture far from American swing roots. In 2002 and 2004, he presented concerts dealing with two important jazz figures of the last 40 years that many resented him for overlooking: Charles Mingus and Ornette Coleman.

Lately, he talks and writes about how great swaths of music in the world are closely related, through drones, repetition and groups of meter. “I wouldn’t say that he’s mellowing,” says Andre Menard, the artistic director of the Montreal Jazz Festival. “But his hard shell of traditionalism has kind of broken open.”

Marsalis’ music has grown in scale and ambition over the past decade. Blood on the Fields, the 1997 Pulitzer-winning oratorio, was a three-hour work on slavery; All Rise, from 1999, for jazz band, orchestra and choir, reflected on the end of the millennium. Both projects were commissioned by Lincoln Center, but he is driven by his own discipline.

Though plenty of people in jazz begrudge Marsalis his success, a few think he has not played to his own strengths as a musician. In 1979, when Marsalis was 17, Gunther Schuller, the composer and historian of classical music and jazz, accepted Marsalis for the summer program at Tanglewood and remained a friend and mentor for years after. “There is no better trumpet player on the face of this earth,” Schuller said. “This guy is beyond belief, what he can do both in classical music and in jazz, technically. But in general I think that Wynton has not grown, has not developed to the extent that I thought he would, in terms of inventiveness and originality as a player and as a composer.”

“Ten years ago,” Schuller continued, “I told him, “You know, Wynton, one of these days you’ve got to take the trumpet out of your mouth. Go somewhere and think. You’re on a merry-go-round of incredible success and financial well-being, but one of these days you should think of your long-range development.’ “

Marsalis does not see it that way. Asked if he was shortchanging his ability to do his own thing, he reacted strongly. “This is my own thing,” he said. “I could play solos all night if I wanted to, and I like playing fourth trumpet in a big band, too.”

Then his answer broadened: “There’s no part of the music or what we do that’s not my thing. If it’s just sitting in the trumpet section, if it’s soloing, if it’s education, if it’s teaching a private lesson or talking to a kid whose parents have waited with him after a gig, if it’s playing Happy Birthday on the phone for an 8-year old. It’s all a part of my thing.”

By Ben Ratliff

Source: Tampa Bay Times