Movement and Music, Both Jazz and Both Live

Just as jazz music comes in many sonic varieties, so jazz dancing can assume many shapes in space. That became clear on Wednesday night in “Jazz in Motion,” a Jazz at Lincoln Center presentation with works by four choreographers, three of them offering premieres.

The scores for all but one dance were by Wynton Marsalis, the music director of the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra. And it was exhilarating to hear live jazz while watching live jazz dancing.

Peter Martins, ballet master in chief of the New York City Ballet, was represented by two works for dancers of his company. At the start of “The Wind Up,” a premiere, Charles McPherson stood alone onstage playing alto saxophone. Moments later, Amar Ramasar entered casually, hands in pockets. But the music’s vitality prompted him to rock from side to side, take a few tentative steps and then burst into energetic scurrying, pausing occasionally to watch Mr. McPherson play.

Mr. Martins was also choreographically represented by “ ‘D’ in the Key of ‘F’ – Now the Blues,” a pas de deux of 1993 with classically based but often languidly romantic steps for Nikolaj Hübbe and Wendy Whelan.

The orchestra was onstage for “Spaces,” Savion Glover’s premiere, which he danced on a platform with a microphone beneath it. Tapping in complex rhythms, he created sonic contrasts by occasionally scraping a heel across the floor.

There were pleasant comic touches, like an imitation of a woodpecker and a goofy sequence of skids and slides. And there were jaunty little ensembles for Mr. Glover, Ben Hosig, April Cook, Cartier Williams and Marshall Davis.

Elizabeth Streb’s “Gauntlet,” the evening’s most elaborate premiere, was the only work with music by a composer other than Mr. Marsalis. Joe Chambers’s score was played by his combo, Joe Chambers and Nommo, and it was full of fascinating layers of drumming, whistling and chiming. But because Ms. Streb deliberately avoids trying to harmonize dancing with music in her productions, the score was simply a background.

The production, designed by Michael Casselli, was dominated by a tall structure from which two concrete blocks swung like pendulums. Members of Ms. Streb’s company, Streb, kept acrobatically dodging these blocks. Although dancers sometimes ran smack into each other, these collisions were deliberate. Fortunately, no one ran into the cement blocks.

Choreographically, “Gauntlet” resembled many of the strenuous pieces Ms. Streb has devised over the years. What made it unusual were video images of the work projected on a backdrop. Because the camera viewed the dancers from above, the production’s shifting perspectives made “Gauntlet” an ever-changing theatrical kaleidoscope.

The program demonstrated that the new Rose Theater in the Time Warner Center is a good space for looking as well as listening. The stage is big. The auditorium resembles a small opera house. But from a dancegoer’s point of view, its shape may be one of its few drawbacks, because the rows of balcony seats that curve forward in a horseshoe shape may have limited visibility when they near the proscenium.

Another awkward touch is the placement of a lighting-control panel near the center of the orchestra seats. Its buttons sometimes flickered during the performance, which may have distracted people seated near it.

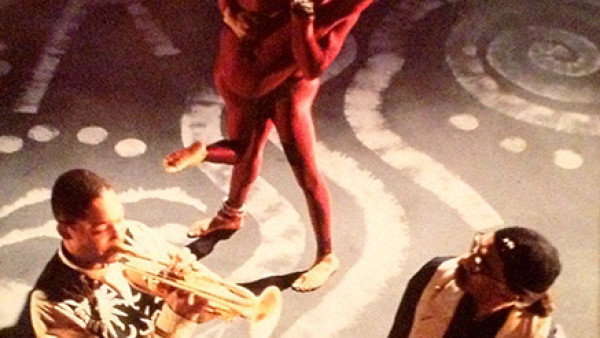

The most musically sophisticated choreography came in excerpts from two works by Garth Fagan, performed by his Garth Fagan Dance. There were two scenes from “Griot New York” (1991). “Bayou Baroque” found groups of unhurried dancers taking their own good time while Mr. Marsalis’s music pushed steadily ahead. “Spring Yaounde” was a duet in which Nicolette Depass and Norwood Pennewell were sometimes so closely entwined that they resembled a single organism.

The other was episodes from “Trips and Trysts” (2000), which had many quirky choreographic changes, as when big leaps to blares of brass came to sudden stops. At one moment parading dancers continued to parade when the orchestra had stopped. But the sounds of their feet and snapping fingers revealed that the spirit of jazz still lived among them.

by Jack Anderson

Source: New York Times