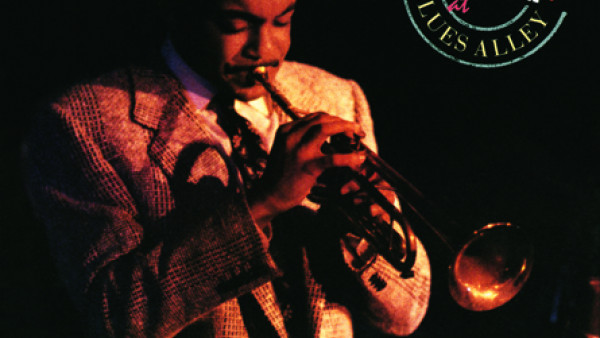

Live at Blues Alley

Great jazz music can claim any space, but the nightclub remains its signature setting, the place where musicians and audience most seek communion in the spirit of swing. Here is music from nights when the spirit was so strong it threatened to swing everybody right out of the building. As a great quartet — Wynton, pianist Marcus Roberts, drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts and bassist Robert Hurst — rip into Charlie Parker’s “Au Privave,” Ray Noble’s “Cherokee,” and accent a cross section of Wynton’s own tunes including “Knozz-Moe-King,” “Skain’s Domain,” “Delfeayo’s Dilemma,” and “Much Later.”

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Quartet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | June 21st, 1988 |

| Recording Date | December 19-20, 1986 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | 487323 2 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download, LP |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| CD 1 | ||

| Knozz-Moe-King | Play | |

| Just Friends | Play | |

| Knozz-Moe-King (interlude) | Play | |

| Juan | Play | |

| Cherokee | Play | |

| Delfeayo’s Dilemma | Play | |

| Chambers of Tain | Play | |

| Juan (E. Mustaad) | Play | |

| CD 2 | ||

| Au Privave | Play | |

| Knozz-Moe-King | Play | |

| Do You Know What It Means To Miss New Orleans? | Play | |

| Juan (Skip Mustaad) | Play | |

| Autumn Leaves | Play | |

| Knozz-Moe-King | Play | |

| Skain’s Domain | Play | |

| Much Later | Play | |

Liner Notes

In December 1986, when Wynton Marsalis arrived in Washington, D.C. for his seventh engagement as a bandleader at Blues Alley, he was 25 years old and already what Duke Ellington termed “a decorated hero and a symbol of glamour.” Marsalis had won many jazz polls and was frequently the recipient of awards both significant and trivial. But, more important than anything else, he had humbly become accustomed to experiencing that most precious of all awards–the feeling of pure affection that comes from the most serious and inspiring listeners. His attire, or battle dress, was that of the radiant prince whose image symbolizes the very elegance of the culture arched in the position of its greatest potency. He was prepared for the ritual of immediacy that is jazz performance, in the sort of form that posed provocative suggestions about the future of his instrument and the future of jazz music itself. Wynton Marsalis was ready to meditate in red, perfectly fuse contemplation and flame, and his band was realizing fresh approaches to collective jazz rhythm with the audacious accuracy of innovation.

Though Marsalis is from New Orleans, his princely aesthetic eminence was welcomed like a local hero. That was more than a little correct: in our world, where meaning and emotion are brought so close by technology–arriving by book, recording, film, television and radio broadcast–those who meet the needs and satisfy the appetites of the soul are local heroes. It doesn’t matter where they actually come from–what race, sex or religion they might be or adhere to–they must speak to the perpetually local concerns of the inner life, if they are to be received as Wynton Marsalis and his musicians were when they went to work in the wonderful city of Washington, D.C.

In the partially lit confines of Blues Alley, the Marsalis band entered, as do all jazz musicians, the world vernacular American myth. But vernacular or not, the myth they addressed had the same components once described by Richard Wagner: “Myth is the primitive and anonymous poetry of the people, and throughout history we find it being returned to and ceaselessly recast by the great poets of cultivated epochs. In myth, in fact, human relationships strip themselves almost entirely of their conventional form which is intelligible only to abstract reason; instead they show the truly human and eternally comprehensible element of life, and they show it in that concrete form, a form exclusive of all imitation, which confers upon all true myths that individual character which is recognizable at the very first glance.” What is so easily recognizable here, and that which is so happily responded to by the audience, is how well the music is held together by the symbolic truth of the myth of jazz. This idiomatic myth is enunciated through the elements so exclusive of imitation–blues and swing. Blues: intimate and spiritual experience–joyous, bittersweet, or longing–ennobled through the poetic grandeur of down-home timbre and intensity. Swing: democratic mobility made transcendent through the supple manipulation of the syncopated. So in the ritual of immediacy and exchange that takes place in a jazz club between the musicians themselves and their listeners, the Blues Alley audience came expecting to hear music, as Art Blakey says, wash away the dust of everyday life.

They got what they were listening for, arriving in the finery that gives a quality of special glamour to the evening, with the women and the men decked out more often than not and ready to bring that extra element of feeling only the best audiences offer. Wesley “Skip” Norris, who was himself impressively decked out on a nightly basis, remembers the engagement quite well. Skip is a Motor City resident and a collector who drives to Washington every December for Wynton Marsalis’ annual engagement at Blues Alley. Of this particular set of performances, Skip says, “I believe that this will go down in history as a high point in Wynton’s early career. He came prepared to let the work of the wood-shed show itself to the extent that no one would have any doubt whatsoever what the deal was. I will never forget how Wynton and his boys played during that run. The music swooped, it swung, it was funky, it was gritty, it did everything in terms of feeling that Ellington and those cats started. I maintain that if I don’t come out of a club literally sweating, then I don’t think enough business was taken care of. On this gig, the perspiration was heavy.”

During the sound check, bassist Bob Hurst referred to the need to “submit to the altar of swing,” which suggests the ceremonial intensity demanded of the phenomenon of swing itself. Marsalis understands that quality in terms of his own development as a player, a development that was initially inspired by the world of the jazz nightclub. “The thing that made me want to be a jazz musician is when I used to go to hear my father and James Black play at Lu and Charlie’s on Rampart Street. I was attracted to everything that went on in a club, even though I didn’t really listen to the music. I liked the environment, the stories people would tell and the little different human intrigues that would be going on. But what made Lu and Charlie’s so fascinating was that it took musicians and put them with listeners and the two made a special feeling together. It was very different from hearing my father and other musicians rehearse. There was something ceremonial about it and when the musicians and the people connected, a very special quality took over the room. It had the intensity of a New Orleans parade compressed into one room. Even then, not knowing much about music, I was aware of the fact that I wanted to be a jazz musician. I wanted to get as close to that feeling as I could. I wanted to create that feeling someday if I could, and I never lost that desire.”

The panorama of passion that Marsalis brings to this recording is superior to that contained in any of his previous work, revealing the development heard only in the art of those who have little time for gloating over past successes to the point of self-congratulatory stagnation. Marsalis is a mercilessly self-critical musician whose playing always contains the quality of talent and desire that makes superb work inevitable. Nietzsche could easily have been writing of the latest shining trumpet light from the Crescent City when he described the qualities of the true philosopher in Beyond Good and Evil, observing that for “every elevated world, a person has to be bred, and often bred as much by his own ambition as by circumstances: each of his virtues must have been individually acquired, tended, inherited, incorporated, and not only the bold, easy, delicate course and cadence of his thoughts, but above all the readiness for great responsibilities …”

No young musician has shown more readiness for great responsibilities than Wynton Marsalis. His dedication to the art of jazz is audible in his growing mastery of the language, his deepening sensibility, and the grasp of the contributions not only of giants such as Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Fats Navarro, Clifford Brown and Freddie Hubbard, but of players less celebrated such as Don Cherry (whom he refers to on Au Privave) and Harry “Sweets” Edison (who is joyously saluted on Autumn Leaves, Skain’s Domain and at one place or another on most of the blues performances).

“From listening to the recordings of Clifford Brown, Miles and Coltrane, and from going to hear my father play, I wanted to learn how to play my instrument and swing. I was so obsessed with getting to the feeling of swing that I didn’t miss one day of at least four hours practice from the age of twelve to nineteen. I would play in any band–concert band, orchestra, jazz band, funk band, wedding band, parade band–just for the joy of learning music and my instrument. New Orleans afforded me the opportunity to experience thousands of hours of music in rehearsals and performance. Thinking back, I recall that the hard work could be lonely and painful, but there is a deep exhilaration that you experience from doing the work. There is another exhilaration beyond that, which is when you have accomplished something. That exhilaration is the same as swing itself. It’s the joy of coming through something, the happiness of getting past a limitation in objective terms, which is what a groove is. The trumpet itself doesn’t care who plays it, or if it gets played at all. It’s a cold instrument that never gives in easily. You have to make it warm. You have to coax everything out of it that you get. That’s what you hear when the masters play it.”

Marsalis is now much more of a master of the instrument than he has ever been, which means that the instrument itself has been extended. The kind of bravura power heard on these two records has little contemporary parallel, if any. There are passages in Skain’s Domain, Chambers of Tain, Knozz-Moe-King and Delfeayo’s Dilemma when Marsalis rises to an intensity similar to that of John Coltrane, where virtuosity, passion and conceptual brilliance make for an aesthetic triangle of intimidating proportions. With the opening track, Marsalis demotes the avant-garde trumpeters one and all, playing with such force and bold fluidity that one wonders what the course of jazz would have been had he arrived twenty years earlier. But he is also able to croon up lucid plumes of melodic invention on Just Friends and Do You Know What I Means To Miss New Orleans that are startling in the maturity of their tenderness and nostalgic sorrow. Then there is example after example of his rhythmic powers, the first fresh conception of trumpet phrasing we have heard in two decades at least. He is, doubtless, the most important young musician in jazz.

His musicians are also remarkable. Marcus Roberts, who was born August 7, 1963 in Jacksonville, Florida, has won jazz piano competitions since 1982, the most recent being the Thelonious Monk in Washington, D.C. in 1987. Roberts is already in front of all the players of his generation, primarily because of his soul ratio and the impressive intelligence that gives form to his improvisations. His twenty choruses on the first version of Juan make clear the number of laps between Roberts and the rest of the pack. The shape of the whole improvisation is held together by melodic, rhythmic and harmonic motifs that are so well controlled and so effortlessly given to idiomatic emotion that his artistic ambition is well displayed. “Melodically,” he says, “I am trying to deal with a certain type of architecture in which the melodic material is not random. I want to choose themes and sub-themes that are developed throughout, from the first note to the last. I learned the importance of this from Monk. What I love about Monk is the lack of speculation in his playing. Every note reflects absolute consciousness. Monk’s music can be appreciated by a person at any level of awareness. That’s how vast his musical universe is. It swings, it’s organized, it’s logical, the blues is totally explored, the orchestral side of the piano is used with profound understanding. Plus, he and Duke Ellington knew the pedals and knew how to get the piano to resonate the way they wanted.

“Melodically, I want the rhythm of each thematic statement to contain swing so that every part of the statement is not only related by theme and harmony but by swing. The playing of McCoy Tyner with Coltrane is important here because he understood individual timbre and combined the ringing and the percussive perfectly. He also knew the role of the piano in relation to the rhythm section. His chords were multi-dimensional in that they would hook up with Coltrane, with Jimmy Garrison, and would complement the sound of Elvin Jones was playing. Rhythmically, I’m working on complete independence of each finger so that I can have rhythmic, metric and thematic counterpoints functioning at the level of absolute swing.” To understand what he means, listen to the way he and Jeff Watts play together on Delfeayo’s Dilemma, or his own playing on track after track–the way he constantly invents spontaneous arrangements that become parts within the entire sound, pivoting from intriguing harmonies to rhythmic and metric superimpositions to blues shouts that bore holes in the molecules of the air.

Robert Leslie Hurst III was born in Detroit on October 4, 1964. He began playing the bass at nine and met trumpeter Marcus Belgrave in his junior year in high school. Belgrave inspired him to become musically serious and Hurst credits him with providing the impetus for most young musicians in Detroit: “He’s always trying to help out the young musicians. Besides being one of the best trumpet players out there, he’s extremely important to the development of serious younger players.” Hurst studied and played with David Baker at Indiana University and is quick to point out how the strong musical foundation Baker provides is applicable across styles. In 1985, Hurst joined the Marsalis band and left in 1987. His contribution to the sound of the ensemble was remarkable. Hurst played lines that kept time or that existed as parts unto themselves, propelling the ensemble through their swing and phrasing. Listen to the way he plays in the out-of-tempo section of Just Friends, where the melodic weight of his notes lift the instrument into the foreground but maintain the registral power so singular to the bass.

“I want,” says Hurst, “to extend on the bass harmonically what was developed by Ron Carter and Paul Chambers. The thing that I’m really trying to shoot for is the rhythmic continuum of a walking bass line and use motifs that move through the form and the harmony but not always in a symmetrical way. I would like to avoid the expectations of phrasing when I can do that without sounding contrived and without losing the swing. I want to phrase quarter notes freely so that they can retain their rhythmic value but imply other meters or phrasing groups. To do this, I might play something a beat late or a beat ahead. So I’m improvising within the rhythmic aspects of the harmony. I met Jeff Watts in 1979 and we played in an after-hours joint in Pittsburgh, and I could tell that he was thinking about that then. From talking with him, I realized that he wanted to get away from obvious rhythms within the form while still playing the form of tune.

“One of the things that I learned from Ron Carter is that he really understood the architecture of the tune. He mastered the pace. When he decided to walk or play a pedal or stay in two or use the consonant or dissonant pedal idea, it gave the bass a much more powerful position in the form. The bass in his and in Mingus’ work before that, they both heard the rhythm section as an integral part of the sound instead of a pedestal for the horns to stand on. Mingus broke all of the confines of the way bass players functioned. He played five and six and seven note groupings. That’s a real high level, which I want to work toward. For now, I try to play more like a saxophonist or a piano player would. Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, melodies like Lester Young would play, Monk and Bud Powell.” All of those aspects of music are already present in Hurst’s style, especially the sense of using the bass as more than a carrier of simple harmony notes. Throughout, Hurst not only creates harmonic shocks through surprising selections of tones, but he also plays and reiterates themes, building upon what has been played around him and sometimes compressing those ideas for the purposes of giving greater form to the group improvisation when he reintroduces them in telling places.

In a master class at Cal Arts, Max roach recently told the assembled students and instructors that he finds Jeff Watts the most exciting of the younger drummers, primarily because of the way he is finding fresh combinations through his independent coordination. That is easily understood if one listens to Watts’ introduction and his six-and-a-half minute feature on Chambers of Tain. The conglomeration of ringing cymbals and complex rhythmic figures actually avoids any single conception of meter or time. What Watts achieves is a powerful, tremulous drone of rhythm that goes in so many directions at once that the listener experiences something akin to pulsive stillness. It is a perfect assimilation of what one hears in African percussion ensembles except that the cymbals themselves and the underlying strain of swing make the whole effort Afro-American. Watts is also quite provocative in his metric flexibility, pulling contrapuntal meters into parts played by one or two limbs while maintaining a steady four/four on the ride cymbal. It is quite doubtful that there is a more swinging player of the brushes in his generation.

Watts was born on January 20, 1960 in Pittsburgh. He began playing around the age of ten, moving from snare drum to drum set at fifteen, studying percussion in high school and for two years at Duquesne University (orchestra, wind ensemble, brass ensemble, percussion ensemble and jazz ensemble). He then went to Berklee in Boston and met many of the musicians who have since made names for themselves–Branford Marsalis, Smitty Smith, Wallace Roney, Greg Osby, Cindy Blackman, Donald Harrison and so on. He joined Wynton Marsalis in 1982 and left the band in 1988.

Of his conception, Watts says, “My favorite drummers are Jo Jones, Kenny Clarke, Roy Haynes, Ed Blackwell, Max roach, Elvin Jones, Art Blakey, Philly Joe Jones, Billy Higgins and Tony Williams, but what I want to do is use ideas about rhythm that are combinations of thematic devices I heard Monk deal with in displacing rhythm. The other things are composite rhythms, meaning whatever somebody played rhythmically, I would try to play everything except what they played. I try to hear what they play and use whatever is left, so as to come close to playing a spontaneous arrangement. During Marcus’ solo on the first Knozz-Moe-King, for instance, he sets up a theme and I play off the idea a beat later. I’m also interested in what I call pure polyrhythms, setting up and implying more than one tempo at the same time, which can result in each rhythm providing an entirely different kind of counterpoint than what we are used to hearing.

“One of the things I’m most interested in at this time, and you can hear it on the long drum solo, is working on a way to get an asymmetrical effect that is an extension of syncopation itself. The main point is to exploit the whole idea of a drum solo, to take advantage of the fact that you’re playing by yourself. Too many drum solos are just displays of velocity and technique, neither of which is essential to the drums. Other instruments can play fast and display technique, but the polyrhythmic possibilities of the drums are unique. That’s what I’m trying to deal with.”

The five-part suite of variations on Chambers of Tain and Watts’ bold approaches, in too many instances to even point out, justify Max Roach’s excitement over his style. We should expect nothing but the best from this surpassingly inventive young drummer.

As a swan song to one of the best bands of the decade, this record should uplift listeners and inspire musicians. Though there are occasional rough moments of the sort one always hears when performances are recorded in clubs, those moments are more than made up for by the phenomenal complexity of the group interplay. Just the different lanes of rhythm they use on Cherokee, where the African approach of rhythm is appropriated for the style of jazz instead of imitated, prove the originality of the ensemble improvising in this band. Many bands indicated this kind of playing, but the control of the forms, the hell-for-leather abandon, and the will to the spiritual powers of swing give a glistening joy to this music, the kind of joy that has always made international the charismatic buoyance of the human heart.

– Stanley Crouch

Credits

DISC 1

1. Knozz-Moe-King

(Wynton Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

2. Just Friends

(John Klenner / Sam M. Lewis) SBK Robbins Music

3. Knozz-Moe-King (Interlude)

(Wynton Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

4. Juan

(Marcus Roberts / Jeff “Tain” Watts)

5. Cherokee

(Ray Noble) Shapiro, Bernstein & Co. Inc.

6. Delfeayo’s Dilemma

(Wynton Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

7. Chambers of Tain

(Kenny Kirkland) kenny Kirkland Music

8. Juan (E Mustaad)

(Marcus Roberts / Jeff “Tain” Watts) Pending

Disc 2

1. Au Privave

(Charlie Parker) Atlantic Music

2. Knozz-Moe-King (Interlude)

(Wynton Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

3. Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans?

(Louis Alter / Eddie DeLange) Shapiro, Bernstein & Co. Inc./Louie Alter Music Publishing

4. Juan (Skip Mustaad)

(Marcus Roberts / Jeff “Tain” Watts) Pending

5. Autumn Leaves

(Joseph Kosma / Johnny Mercer / Jacques Prévert) MOrley Music Co./S.D.R.M.

6. Knozz-Moe-King (Interlude)

(Wynton Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

7. Skain’s Domain

(Wynton Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

8. Much Later

(Wynton Marsalis) Skayne’s Music

BIEM/STEMRA

Producer: Steve Epstein

Executive Producer: George Butler

Chief Engineer: Tim Geelan

Assistant Engineers: Phil Gitomer, J.B. Matteotti

Technical Supervisor: Hank Altman

Mixing Engineer: Tim Geelan except on “Do You Know What It Means To Miss New Orleans”

Mixing Engineer: Delfeayo Marsalis

Special Editor: Jason Marsalis

Facilities provided by Remote Recording Services, Inc.

Transportation by Michael Hill.

Recorded digitally “live” onto the SONY PCM 3324 Digital Tape Recorder.

Monitor Loudspeakers: B&W 801

Post-Production Facilities:

CBS Recording Studios

49 East 52 Street

New York, NY

Performance Dates: Friday, 19 December and Saturday, 20 December 1986

Band Members:

Wynton Marsalis, Trumpet

Marcus Roberts, Piano

Robert Leslie Hurst III, Bass

Jeff “Tain” Watts, Drums

I would like to thank Jason Marsalis, Delfeayo Marsalis, Billy Banks, Mike Hill, Diana Kaiser, Colleen Evans, everyone at Blues Alley, DJ, Randi and everyone at APA.

Booking Agency:

Agency For The Performing Arts

9000 Sunset Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA 90069

213-273-0744

Agency For The Performing Arts

888 Seventh Avenue

New York, NY 10106

212-582-1500

Exclusive Personal and Financial Management:

A.M.G. International

Edward C. Arrendell II

Vernon H. Hammond II

PO. Box 55398

Washington, D.C. 20011

Special Thanks to the Vista International in Washington, D.C.

Art Director: Jo DiDonato

Cover Photography: Caroline Greyshock

Personnel

- Jeff “Tain” Watts – drums

- Bob Hurst – bass

- Marcus Roberts – piano

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Just Friends - Wynton Marsalis Quintet in New Zealand 1988

-

Videos

Videos

Juan - Wynton Marsalis Quintet (1987)

-

News

News

The 10 Best Wynton Marsalis Albums

-

Wynton's Blog

Wynton's Blog

I always remembered any club that had the courage to hire me when I first started

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis: Reclaiming the Jazz Tradition

-

News

News

Sallying through the Alley with Marsalis