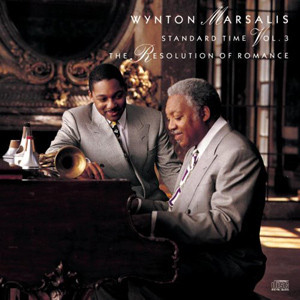

Standard Time, Vol. 3 - The Resolution of Romance

Accompanied by Reginald Veal on bass and Herlin Riley on drums, Wynton joins one of jazz’s finest pianists, his father, Ellis Marsalis, on this album of ballads and blues. Selections include “My Romance,” “Where or When,” and “Skylark,” and three smoking originals “In the Court of King Oliver,” “Bona and Paul,” and “The Seductress” – which promise to become standards in their own right. Dedicated to matriarch Dolores Marsalis, the entire session sings with solos and group playing that respond to, and extend, the lyricism of jazz’s great instrumentalists, from Louis Armstrong to Johnny Hodges to Miles Davis and John Coltrane, and its signature singers, from Bessie Smith on through to Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughn, and Ella Fitzgerald.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Quartet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | May 15th, 1990 |

| Record Label | CBS |

| Catalogue Number | 466871 2 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download, LP |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| In The Court of King Oliver | 4:31 | Play |

| Never Let Me Go | 1:46 | Play |

| Street Of Dreams | 4:07 | Play |

| Where Or When | 2:51 | Play |

| Bona And Paul | 1:46 | Play |

| The Seductress | 2:56 | Play |

| A Sleepin’ Bee | 3:16 | Play |

| Big Butter And Egg Man | 4:45 | Play |

| The Very Thought Of You | 5:37 | Play |

| I Cover The Waterfront | 4:53 | Play |

| How Are Things In Glocca Morra? | 2:58 | Play |

| My Romance | 1:50 | Play |

| Everything Happens To Me | 5:05 | Play |

| Flamingo | 3:21 | Play |

| You’re My Everything | 3:25 | Play |

| Skylark | 2:56 | Play |

| It’s Easy To Remember | 4:07 | Play |

| Taking A Chance On Love | 3:50 | Play |

| I Gotta A Right To Sing The Blues | 5:00 | Play |

| In The Wee Small Hours Of The Morning | 1:57 | Play |

| It’s Too Late Now | 2:55 | Play |

Liner Notes

This album is another sort of victory for Wynton Marsalis. In tone, in phrasing, in the dreams and recollections of the face-to-face forces that provide the details of the heart’s diary, Marsalis has arrived of the heart’s diary, Marsalis has arrived at a new level of lyrical authority and sensual clarity. The relaxed beauty of this recording separates it from all of his previous efforts and documents the development that has come of a long march toward expressive purity a march that has cost much time and has demanded much patience in the face of slowly decreasing disappointments. There is no other way to attain the intimate command heard here, a craft as important to the meaning of romance in literal terms as it is to the artistry, so glowingly audible on this recording. And though Marsalis has recorded a number of impressive ballads under his own name as bandleader before, he has never previously been able to deliver the wisdom of tenderness and the delights of romantic love with such ease. Here he stands up to the challenges set by the grand masters of the jazz idiom, those who have brought to the popular song the proper injections of serious romance, of rhythm, of blues, of the slow dance closeness when the band is ready to leave and the place is about to close. Wynton Marsalis joins those jazz musicians who have crooned the popular song down from the balcony of sheet music, swept it off the Broadway stage, snipped it free of the sentimental bonds that have denied the love song that intimacy jazz so clearly weaves with the swells of adult expectations and memories.

Besides Marsalis’ own development, the force of heart and the rhythmic finesse heard in the lyricism of this recording are due to the presence of his father, Ellis, at the piano. “I always wanted to do an album with him, but I never felt prepared because I didn’t play well enough on changes and have a sound good enough to pay the kind of homage to my father that I really felt. Just having the opportunity to listen to his sound for all of those years when I was growing up was a tremendous inspiration for me and for my brothers, all of us. The greatest influence on me was seeing his dedication to music during the many times when he wasn’t playing gigs that much. Even without any work and no money coming in from music, he had such true love for the music that he didn’t let anything shake his confidence in the power that comes from really working on your sound and not trying to avoid any of the things you have to know if you’re truly going to be a jazz musician. The kind of belief he had in music would make you realize that you can only go forward by facing the obligation of mastering the weight of what the titans of the idiom have laid down.”

That understanding is part of what makes Wynton Marsalis not a conservative, but a radical. As he points out, “If I was a conservative, I would go along with trends, which is what you do if you’re conventional today. If you play jazz, you put yourself outside of that and you also put a lot of challenges on yourself – if you really want to play. Your horn will always tell you what you still have to work on. It becomes very clear to all concerned what the real deal is. There is so much music out there to deal with that you sometimes can’t believe it. It doesn’t matter what instrument you play either. There are so many forms and so many styles and colors to come to terms with. The demands are almost intimidating. But if you humble yourself before all of that music, things will slowly come together.”

That humbling, that willingness to put in the time to truly learn what jazz is and how it works, that desire to achieve a functional aesthetic understanding of the sweep of the art is heard now in what Marsalis brings to his horn, just as it is heard in nightclub and concert performance with his working band, which is now perhaps the best in jazz. What Marsalis is doing is expanding our expectations of a jazz musician’s authority, something that has not functioned in this art since the Ellington band and the best of Mingus. Where jazz musicians have traditionally only been able to play the styles they grew up on, Marsalis is now saying, through his horn and with his band, that a true jazz musician should be able to play every style with imaginative authority.

“My ambition is to consolidate all aspects of the tradition so that I can really express what it means to be a jazz musician. I want to play jazz, not a specific style. I want to be somebody who plays the music, not just bebop or swing or New Orleans music. And the only way to get to a certain level of quality or timelessness is to make sure that everything you do illuminates the fundamental propositions of the art form. On this record, I’m dealing with all of the mutes, looking at all of those colors, and I’m thinking about all of the styles of trumpet from King Oliver through the swing era and Clark Terry, who was one of my first influences. But I’m not dealing with parody.

“I’m trying to deal with all of the stuff I hard standing up next to musicians like teddy Riley, who is the master of New Orleans trumpet; standing next to Doc Cheatham and Sweets Edison and Clark Terry. Musicians like that he something you really need to know. I know I need to know it.

They are dealing with nuance, form, and clarity of projection on the highest artistic levels. What these men are addressing is the subtlety and the scope, colors and techniques the jazz tradition has given to the language of brass. They have been part of the expansion of the expressive qualities of the trumpet in American music. When you hear musicians like that play, you understand how the singing tradition from blues influenced instrumentalists to create a vocabulary that could stand up next to the emotional clarity of those singers. It’s the kind of thing people like King Oliver passed on to Louis Armstrong and Rex Stewart passed on to Clark Terry.”

It is that grasp of the weights and subtleties of the jazz tradition that gives Marsalis such imposing presence in our time. In musical terms, he is a renaissance man in more ways than one. Not only is he in pursuit of a scope of musical understanding that has little precedent, he is also at the forefront of a movement of young musicians who understand the difference between aesthetic skills and the rhetoric of purported innovation. Marsalis and these other young musicians arrived at a time when the music was in great trouble, having sunk down into a dark age of ineptitude, pretension, and commercialism. Knowledge of real jazz seemed to be slipping away. But now things are quite clear and the ranks of serious young jazz musicians keep growing.

“I made this album because I’m still working on growth in the arenas where things have been made obvious, in terms of artistic intent and achievement. One of the elements of jazz music is the standard song. To deal with the moods and the colors, the harmonies and the motion of the tunes is something that can’t be dismissed. There is a lot of maturity in these songs from a compositional standpoint. The people who used to write popular songs really understood music. When you try to play these songs you find that out. I heard my father playing these songs in clubs so beautifully. What I love about his style is that he’s got a serious touch and he’s always listening and always trying to make everybody in the band sound better, which is the best way to play. You improvise for the greater good, not just to show off something you practiced and are so proud of that you’ll play it at everybody else’s expense. Not my daddy. The feeling in his playing comes through as just what it is: deep interest and concern for things human and musical.”

It was from his father that Marsalis first heard the importance of addressing the standard repertoire, which binds together the finest jazz musicians, from Armstrong to Coltrane. Marsalis recalls his father telling him, “Son, you can’t avoid these standard songs. You’ve got to learn to play on changes.” Of course, changes are not all the standard songs are about, however important their harmonies might be. They are also about singing, about giving vent to those revelations, about what Ellington called “The world’s greatest duet” a man and a woman going steady.” Those revelations stretch from joy to heartbreak, and the lyrical impulse jazz has always drawn from the purity of the blues brings a disposition that often reshapes and increases the human value of songs that are already attractive in form and content.

One way that quality is added to the romantic song by relaxing into the mood that demands control of tone, where shading and texture are as important as the notes themselves. “When you are playing soft,” says Marsalis, “there are an infinite number of subtleties that you can discover the same way you do when any activity is approached softly and slowly. That’s what I call the resolution of romance. A lot of people hear the word resolution and they think of something overt or harsh, but there is a sort of soft resolve that we all know has true power. In musical terms, you hear this whenever Ben Webster plays a ballad, or Johnny Hodges or Louis Armstrong, or Bird, or Trane, Billie Holiday, Nat Cole, the jazz miles Davis. All of these people affirm the force available to the musician who is willing to deal with nuance on the level that it becomes available when you play softly and slowly.”

Wynton Marsalis is now getting with that force of nuance of a scale of expressive depth and musical certainty that even further distinguishes what is surely one of the most impressive talents of our age. Listen to “never Let Me Go,” “Where Or When,” or “How Are Things in Glocca Morra?” as but three examples of the invincible evidence that rises into the air from this recording. Clearly, few in the entire history of jazz have had tones equal to his, and listening to the open horn performances clarifies his link to Clifford Brown, the dominant influence of jazz trumpet playing of the last three decades. Then there are all of the colors he achieves with the various mutes – the straight: “In The Court Of King Oliver”; the bucket: “I Cover The Waterfront” and “Flamingo”; the hat: “Taking A Chance On Love”; the cup: “Big Butter and Egg Man”; harmon: “Bona And Paul.” Or witness the startling performance with the plunger of “The Seductress.” For swing and rhythmic complexity, the work with the cresting notes and displacements of “I Gotta Right To Sing The Blues” would perhaps make Armstrong himself proud. The melodic and smooth invention of “You’re My Everything” that Marsalis leans into the atmosphere, is but part of an overall group swing most will admire. The other songs hold the line, allowing us varied entries into lyricism.

An aspect of that variety results from the color this recording achieves by using all of the key signatures except D flat. This is not a display, but it is the attitude Marsalis got from his father, who used to always tell him when the trumpeter would ask what key something was in, “Son, there are no keys. There’s only they key of music.” In other word, music is the goal and keys should never block the professional from making an artistic statement.

For those who wonder what the Ellis Marsalis story is, go to “Street Of Dreams”: control of inflection, rhythm, harmony, melodic development, and swing will be evident. There are other features, solo performances by the patriarch and many examples of exceptional accompanying skills.

Reginald Veal and Herlin Riley perform, as they always do, superbly and with insights into the tasks of the bass and the drums that have made them one of the superior combinations of the day. In all, Wynton Marsalis has done notable work for the blushing and broiling heart at the center of all romantic notions. By doing so, he further establishes not only the grandeur of a singing tradition of instrumental interpretation but his own indelible place in it.

–Stanley Crouch

Credits

1. In the Court of King Oliver

(Wynton Marsalis) – Skaynes Music

2. Never Let Me Go

(Ray Evans / Jay Livingston) Famous Music Corp.

3. Street of Dreams

(Sam M. Lewis / Victor Young) EMI Miller Catalog

4. Where or When*

(Lorenz Hart / Richard Rodgers) Chappell & Co.

5. Bona and Paul

(Wynton Marsalis) – Skaynes Music

6. The Seductress

(Wynton Marsalis) – Skaynes Music

7. A Sleepin’ Bee

(Harold Arlen / Truman Capote) Harvin Music Co.

8. Big Butter and Egg Man

(Louis Armstrong / Percy Venable) MCA Music Pub.

9. The Very Thought of You

(Ray Noble) WB Music Corp.

10. I Cover the Waterfront

(Johnny Green / Edward Heyman) WB Music Corp.

11. How Are Things in Glocca Morra?

(E.Y. “Yip” Harburg / Burton Lane) Chappell & Co.

12. My Romance

(Lorenz Hart / Richard Rodgers) T.B. Harms

13. Everything Happens to Me

(Tom Adair / Matt Dennis) Dorsey Bros. Music

14. Flamingo

(Edmund Anderson / Ted Grouya) Tempo Music

15. You’re My Everything

(Mort Dixon / Harry Warren / Joe Young) WB Music Corp./Warock Corp.

16. Skylark

(Hoagy Carmichael / Johnny Mercer) Frank Music Co./Twentieth Century fox Muscic

17. It’s Easy to Remember

(Lorenz Hart / Richard Rodgers) Famous Music Corp.

18. Taking a Chance on Love

(Vernon Duke / Ted Fetter / John Latouche) EMI Miller Catalog

19. I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues

Harold Arlen / Ted Koehler) WB Music Corp./Pending

20. In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning

(Bob Hilliard / David Mann) Better Half Music/Rytvoc Inc.

21. It’s Too Late Now

(Burton Lane / Alan Jay Lerner) Pending

*Recorded with one stereo microphone

Wynton Marsalis, Trumpet & Vocal

Ellis Marsalis, Piano

Reginald Veal, Bass

Herlin Riley, Drums

Producer: Delfeayo Marsalis

Executive Producer: George Butler

Recorded and Mixed by Patrick Smith using the Acoustisonic Process E

Extended Mixes: Tim Geelan

Additional Engineering: Peter Doell

Assistant Engineer: Sandy Palmer

Mixed at Marathon Studios, CBS Records Studios and New Age Sight & Sound

Mastered at Europa Disc, New York City

Edited by Meean-Cheem Ustoo

To obtain more wood sound from the bass this was recorded without usage of the “dreaded” bass direct

Piano provided by Steinway

Exclusive Personal and Financial Management:

AMG International, PO. Box 55398, Washington, DC 20011

Edward C. Arrendell II, Vernon H. Hammond III, Partners

Booking Agency:

Agency for the Performing Arts

888 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY

10106, (212) 582-1500

Agency for the Performing Arts

9000 Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90069, (213) 273-0744

Special Thanks to Steve Epstein and Tim Geelan

Photography: Ken Nahoum

Art Direction: Josephine DiDonato

We would like to dedicate this recording to Dolores who held it all together. We love you very much.

-Wynton and Ellis

Personnel

- Reginald Veal – bass

- Ellis Marsalis – piano

- Herlin Riley – drums, tambourine

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

The Very Thought of You - Wynton Marsalis Quintet at Jazz in Marciac 2016

-

Videos

Videos

Everything Happens To Me - Wynton Marsalis Quintet at Jazz in Marciac 2013

-

Videos

Videos

In The Court of King Oliver - Wynton Marsalis Septet in Warsaw (1994)

-

Videos

Videos

The Very Thought of You - Wynton Marsalis Septet in Seoul, South Korea

-

Videos

Videos

Wynton and Ellis Marsalis talking about their album: Standard Time Vol.3

-

Videos

Videos

The Very Thought of You - Wynton Marsalis Septet in Berlin (1989)

-

News

News

He trumpets mature jazz

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis: Reclaiming the Jazz Tradition