He trumpets mature jazz

For Marsalis, jazz means the mainstream from the early New Orleans and big-band sound to ’40s bebop and the variations on bop that came in the ’50s. He has paved the way for the re-emergence of mainstream in jazz records.

Wynton Marsalis wasn’t actually born wearing a banker’s suit, a tightly knotted tie and a solemn, knowing expression on his face. Sure, for the past decade the 30-year-old trumpet player has led a resurgence of serious, “mature” traditional jazz and has taken every opportunity off the bandstand to preach about its importance.

But he had another life when he was growing up back in New Orleans. He knew about jazz, but what he did was play in a funk band, with brother Branford. He got down! Punched out honking notes over that percolating rhythm. Knew it was music designed “to get some teen-agers to go to bed with each other” and didn’t mind a bit.

“From the age of 12 to 16, that’s all I played,” he said by telephone from Shreveport, LA., where he was performing on a tour that will bring him to a sold-out concert at 8 Monday night at the Grand Opera House in Wilmington. “It’s not like I stayed home abhorring it. I liked it. I was a teen-ager, too.”

But here’s the important part for jazz fans: Marsalis heard a lot of jazz through his father, Ellis, an important music teacher who also performed. It just didn’t dawn on Wynton that he might trade chugga-chugga-chugga for bebop harmonics and improvisational solos.

“That was my father. You don’t really connect to your father at that age,” said a laughing Marsalis, who started the interview sounding sleepy but quickly warmed up to the subject. “I knew what he played and liked it, but it didn’t connect with what we were doing.”.

He also knew about classical music and played a fair amount as a teen-ager. By the time he moved to New York and entered the Juilliard School in 1979 to study it, enough jazz had sunk in that he was moved one night to sit in with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

Soon, he was a Messenger himself (kind of prophetic, huh?); not long after that he formed his own band. In 1984 he won a Grammy for his second jazz album and for a classical album as well. For Marsalis, jazz means the mainstream from early New Orleans and the big-band sound to the bebop of the ’40s and the variations on bop that followed in the ’50s. He and dozens of other young jazz musicians for whom Marsalis has paved the way have re-established the importance of the mainstream in the jazz recording industry.

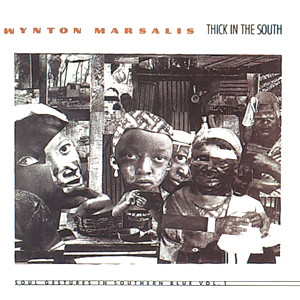

Pretty conservative, say his critics. What is he, some kind of 60-year-old in a 30-year-old’s body? Why isn’t he playing that catchy, trendy, best-selling pop-jazz fusion favored by the likes of David Benoit and David Sanborn? Marsalis doesn’t want to hear it. “Everybody knows it’s more conservative to go with what’s hot,” he said. “If you want to be conservative, do what everybody else is doing. If everybody put on a blue wig and you do the same, that’s not outrageous.” Marsalis put on a “blues” wig with his new recording, an outstanding three-disc set (sold separately) called “Soul Gestures in Southern Blue” (This recording might be as close to Marsalis as you’ll get this week if you don’t already have tickets for Monday night).

All the music is based on the blues, but don’t expect Muddy Waters or Blind Lemon Jefferson. The blues form is used subtly, as a springboard. “Blues music is the basis of jazz,” Marsalis said. “It’s a system of harmony, a way to organize the notes and the tone. It contains a lot of melodic material that can be used. It encompasses a lot of the percussive aspects of jazz music”.

You’ll hear bits of everybody from Jelly Roll Morton to Charlie Parker and John Coltrane on the trilogy. The rhythms vary, though a kind of loping, insouciant beat often dominates. The playing is sensual, lyrical, sometimes a bit edgy, with a few of the growls and squawks that jazzmen can’t resist, but not many. Elvin Jones, who used to play drums with Coltrane, and veteran bop sax man Joe Henderson play on the first disc. Young Marsalis regulars play on all three including several who will be with him at the Grand.

Another sound that slips into “Soul Gestures in Southern Blue” is Duke Ellington’s. In fact, Marsalis believes Ellington is the most important jazz musician. One reason: “His conception was comprehensive. “He wrote music for the concert hall, the dance hall, the church. He wrote music for the bedroom; he wrote music for shows; he wrote music for two or three movies. And all his music was so great.” On top of that, “He could play piano, and he kept his band on the road for 50 years.”

Would Marsalis consider forming a big band like Ellington’s? “I’ve thought about it, but my writing has to come a long way.” He already waited years before recording another kind of music he loves the standards found on two volumes of “Standard Time,” the first released last year and the second this year. “To play those kind of songs was really a step up for me. The people who wrote those tunes Rodgers and Hart, Harold Arlen, Irving Berlin and Hoagy Carmichael, to name a few come from a tradition of Brahms and Schubert, and that adds a certain level of harmony and melody.”

Their greatness, Marsalis said, also lies in their intention “to shape an American idea with their music. They aren’t just great because they’re old.” For all his praise of older composers and jazzmen – and for all of its reciprocation – some jazz veterans sniff that Marsalis hasn’t paid his dues. Didn’t schlep around in sleazy clubs for a hundred years before he found fame. More exasperation. “A lot of times older musicians don’t know what we had to do.”

For today’s young musician, the problem has been “isolation.” “When the older musicians came up, there were a lot of people to play with. For me, there were maybe two other people I met before I was 20 who wanted to play serious jazz. The problem is that there aren’t enough jobs for younger musicians to learn on. That’s why I always support younger musicians.”

But aren’t a lot of post-Marsalis jazz players recording now Marcus Roberts, Marlon Jordan, Roy Hargrove and Antonio Hart, to name a few? “Just going into the studio doesn’t get it,” Marsalis said. “They don’t know what they need as a context to develop themselves in.” But it can be done, even in isolation. Even if you’ve spent your formative years churning out that burning funk.

by Gary Mullinax

Source: The News Journal Wilmington