Levee Low Moan (Soul Gestures In Southern Blue, Vol. 3)

The album is part of Marsalis’ three-album Blues Cycle, Soul Gestures in Southern Blue. The Blues Cycle is a unique suite that explores the moods, colors, harmonies, and rhythms of the blues sound. “Levee Low Moan” is a tribute to the singing horns tradition within jazz music.

What we hear in Levee Low Moan is the concluding breakdown of the blues beat. That beat, as Wynton Marsalis knows so well, is a mood, a feeling, a condition of the spirit, an affirmation of the variety and the community the finest art speaks of with unflinching consistency. Through those cold brass-bodied wind instruments, through those drum heads, cymbals, bass strings, piano keys, hammers, and strings, the cane reeds and so on, comes the warmth that gives another set of examples to what Ellington meant when he wrote in A Drum Is A Woman: “the pretty part is in the heart, the beat’s in the feet.”

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Sextet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | July 30th, 1991 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | CK 47975 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download, LP |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Levee Low Moan | 11:14 | Play |

| Jig’s Jig | 8:49 | Play |

| So This Is Jazz Huh? | 7:02 | Play |

| In The House Of Williams | 10:05 | Play |

| Superb Starling | 11:38 | Play |

Liner Notes

Now and again, jazz is given fresh distinction by the reassertion of the timeless fidelity of the essentials, the basics, the bone and marrow of the music’s soul. Wynton Marsalis’ three album Blues Cycle, Soul Gestures in Southern Blue, is such a moment. Nothing of this size has ever been done with the blues sound before. Fully aware of the limitless variety possible within the big feeling of the blues, Marsalis has organized each album as a decidedly unique suite in itself, but one that is best appreciated as part of an overall statement exploring the moods, the colors, the harmonies, and the rhythms of the form that has had the largest influence on American music. The result is a Blues Cycle made formidable by the vital quality that soothes as it grooves, that elevates as it gets down, that sometimes achieves mystical radiance as it sops the spiritual indigo from the gutbucket, that brings sophisticated insight to its sensuality, and utilizes its dance beats with a down-home hothouse honor. Doubtless this is contemporary blues at its most exquisite, a statement of epic feeling for those who would like to know what artistic time it is in jazz and American music at large. Each of the three albums chime out this hour of our time so clearly that Soul Gestures in Southern Blue allows us to hear anew the charismatic rules of rhythm and tune.

LEVEE LOW MOAN

There is a long tradition within jazz of what were once known as “singing horns,” the use of instruments to emulate the sound of song as it rises up against the sky, the sun, the moon, and the night; or as it whispers those delicate testimonials to erotic yearning; or as it shouts out the affirmation of the flesh and the soul in a world as molten with transcendence as its treacherous with destruction; or as it laughs and chuckles into the sometimes funky breath of fate when not at the foolishness of mortal obsessions; or as it makes audible the combination of the moan and the sigh that cannot be repressed when the evident mysteries of beauty and human feeling are too obvious to ignore. From such a tradition comes Levee Low Moan; every composition is some sort of song balanced atop the dancing pulsation of a groove. Here is blues song instrumentally executed with the lucidity that comes of soul, command, and inspiration. Though initially intended as the second volume of his previous album The Majesty Of The Blues, and recorded during the same period, it works much more effectively as the concluding third of the Wynton Marsalis Blues Cycle.

As a unit of music, Levee Low Moan fulfills its position in the Blues Cycle perfectly; its sextet instrumentation provides quintet albums while maintaining the elaboration and recapitulation of fundamental gutbucket feeling that makes the overall effect of Soul Gestures in the Southern Blue so unprecedented. Where the styles heard from Elvin Jones, Joe Henderson, Robert Leslie Hurst, and Jeff “Tain” Watts on Thick In The South were very different from those Todd Williams, Reginald Veal, and Herlin Riley brought to Uptown Ruler, the addition of Wes Anderson’s alto saxophone and the focus of the compositions on this recording add up to the last part of a musical monument, one that has the organic power of statues after Praxiteles brought the accuracy of swing to Greek sculpture by breaking down the human form’s dimensions so that he could give the feeling of flesh and personality to stone.

What we hear in Levee Low Moan is the concluding breakdown of the blues beat. That beat, as Wynton Marsalis knows so well, is a mood, a feeling, a condition of the spirit, an affirmation of the variety and the community the finest art speaks of with unflinching consistency. Through those cold brass-bodied wind instruments, through those drum heads, cymbals, bass strings, piano keys, hammers, and strings, the cane reeds and so on, comes the warmth that gives another set of examples to what Ellington meant when he wrote in A Drum Is A Woman: “the pretty part is in the heart, the beat’s in the feet.” For each of these melodies, there is a particular groove, some variation on the dance rhythms that have always been tango-close to swing. But because the beats are not static, the swing is as much a response to the variations as it is a steady pulsation of community.

Marsalis used these grooves as he has others, for the express purpose of avoiding the monotony that can set in when bands lock into the same beat for every piece. This is not to say that there have not been truly great bands that almost exclusively played fast, medium, and slow versions of straight 4/4 but that Marsalis is also after the largest array of unpretentious musical devices he can make use of, that he can tailor for specific expressive purposes. “From listening to Duke Ellington,” he says, “I began to think about how music could sound if you didn’t avoid making every detail specific – the melody, the harmony, the voicing, the tempo, the groove. He also made me realize that a groove is as important a part of composition as anything else. Because we are so often unconsciously influenced by the practices of European music, we sometimes forget how much happened when the drums and the rhythm section developed in American music. A whole other are of musical elements was introduced that even the greatest European composers such as Bach, Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Wagner, and so on didn’t really think about. In their music the beat was in the phrasing of the ideas; there wasn’t a separate orchestral unit that addressed the form, the harmony, the tempo, and the various levels of the beat spontaneously. So it seems to me that if one is truly interested in jazz composition as defined by its greatest exponent, Duke Ellington, then one will look into the musical potential that is waiting right there for you in those grooves. Now I study grooves as much as I do anything else.”

Marsalis is absolutely correct. The rhythm section constitutes an ensemble-within-an-ensemble. It is a self orchestrating unit that is allowed the freedom to use the chords, the tempo, and the beat in response to what is going on as the group improvisation unfolds. Great rhythm sections know how to give each featured player the version of the basic material that will best suit his or her taste — and that will most inspire, support, and sympathetically challenge the musician in the limelight. But it is that limelight itself which has had a detrimental effect on the quality of jazz listening. When one pays attention to, say, the horn player, and perceives the rhythm section only vaguely, as no more than a background holding the tempo, much is missed. And since Levee Low Moan so clearly benefits from the marvelous rhythm section of Marcus Roberts, Reginald Veal, and Herlin Riley, it would do all concerned some good if close attention is given to what they do with each of these compositions – how they interact with each other and with each of the horns.

Herlin Riley is perhaps the finest drummer to arrive in jazz from New Orleans since the innovative Edward Blackwell and the lesser known James Black. As this recording shows, he is already a master of sustaining and varying the components of grooves, of using his set for many different colors and effects, and of adjusting to the most subtle changes with unobtrusive immediacy. Listen to how differently he plays on the first three selections, getting timbres out of his instrumentation that would make the uninitiated think he had switched drum sets from one piece to the next. As with all great drummers he can, as is so easily observed on “Jig’s Jig,” maintain a dialogue with the featured player that inspires that player’s direction in rhythm and phrasing. Another of his gifts is the ability to relax into each groove so that it has its own character and allows the featured player to move through his improvisations easefully. That relaxation brings a rhythmic confidence to the sound of Levee Low Moan as an entire effort and reminds us of how close in achievement what Herlin Riley does here is to Vernell Fournier’s classic work with Ahmad Jamal and Israel Crosby.

Throughout, Reginald Veal proves himself capable of doing the same things with his instrument that Riley does with his. He fits into each piece perfectly and exploits the colors of his bass with the sense of timbral possibility that Mingus was perhaps the first to bring to fruition. Veal is aware of how many different ways a plucked note can sound and how differently a note comes in the ear when the string is allowed to buzz against the fingerboard. His tone is extremely dark, and he has a talent for creating bass parts so organic that they change the entire ensemble sound as he decides how to play them and where to put his decisions for maximum effect. The vocal-percussive style he is developing is especially evident on the concluding ensemble choruses of the title track, while his skill at pivoting off every element in the improvising environment is equally easy to make sense of on “Jig’s Jig,” just as his gift for lyrical accompaniment rises forward with clarity throughout. “So This Is Jazz, Huh?” Whatever the future of jazz bass might be, there is no doubt that Reginald Veal will have a starring role in the development of its story.

Marcus Roberts is again documented showing the Secretariat relationship he has to other young piano players. What sends him so far ahead of the pack is his sensitivity to every aspect of music and every role that a jazz pianist is required to fill if the music is to move toward the winner’s circle reserved for those who best understand and execute their part of the collective discipline that so defines jazz. Roberts has the same humility before the groove that Wynton Kelly had. It was Kelly who said he was most interested in getting to the swing, and that once he got there, he didn’t care if he “soloed.” Roberts plays with that same kind of ensemble attention and concern. He knows how and when to work on an improvised arrangement beneath the featured player, how and when to engage in a dialogue with that player, how and when to submerge himself into the chords and their colors so successfully that the piano seems to disappear into the overall timbre of the music. And in his features, as one can observe on “So This Is Jazz, Huh?” his command of the keyboard’s pigments is sometimes breathtakingly precise. But it is all in the interest of “the bittersweet song of spiritual concerns.” That level of soul and rhythm is so obvious in the title track’s piano feature that those who would argue against his preeminence have perhaps not listened closely enough to what Roberts is laying down out here. If not, when they do hear him, they will know what all of the young musicians who have truly addressed his achievement already acknowledge: He might still be developing, but Marcus Roberts has entered into the timeless relationship with soul that all great musicians have in common.

Todd Williams and Wes Anderson have important things in common, however differently they might play their saxophones. Each has worked at getting the sort of tone that allows a personalization of the singing horn tradition. Both are already able to play blues with the kind of authority one feels shocked by as the notes of their features on the title track continue to move out of the bells of their saxophones. Each is capable of stepping into the dance groove of “Jig’s Jig” and throwing down some rump-oriented indigo grit. Both also possess lyrical inclinations that seem to make simple the passover from the bondage of the mind to the promised land of the unfettered melodic passage. They are perfect foils for one another, and when they are asked to do battle on the field of crooning, as they must on “Superb Staling,” one might be reminded of how rich a tradition of elevating debate we have, both in this country and in the line that leads back to Africa on one hand and to the Roman senate on another. With those two saxophones, Williams and Anderson fulfill a structure conceived for development by improvised dialogue, at once in the tradition of Coltrane’s and Adderley’s exchanges on “Two Bass Hit” but also reflective of the best that has happened in the nearly 35 years since. At every turn throughout the album, each man sings out his individual idea of his horn’s tradition with integrity, rhythm, and spirit. Few stand with or near them at the forefront of contemporary saxophone playing by the young and serious.

Before concluding with some remarks about the leader himself, here are his words describing each of the compositions his musicians play on this last third of Soul Gestures In Southern Blue: “Levee Low Moan” – the sound of a fog horn in the distance on the Mississippi. Or perhaps the cry of a forlorn lover overcome in a moment of private anguish. Or both of those and the sound of a couple slowly swinging, rising softly above the counterpoint of the river’s to and fro.

“Jig’s Jig” – a picture in tone of what a child sees when he or she looks into a kaleidoscope for the first time. Because this is blues music, we must give the name a danceable groove. Thus, “Jig’s Jig.”

“So This Is Jazz, Huh?” – what is asked by those who don’t know. But once they find out, well, they never forget.

“In The House Of Williams” – fried chicken, barbequed ribs, collard greens, black-eyed peas, cornbread, various sweet rolls, macaroni and cheese, potato salad, not to mention that sweet potato pie – all lovingly prepared with the greatest culinary expertise. Truly an epicurean delight. This is how we eat in St. Louis when we go to the Williams household and are privileged to put our feet under a table graced by food given the touch and care of Todd’s mother.

“Superb Staling” – a bird of magnificent plumage and two distinctly different personalities. One is friendly and inviting, the other fierce and inhospitable. Both, however, love to sing and swing the blues …in any key.

Given the quality of the playing done by his musicians and by himself, Marsalis should be very proud of this recording. It sounds like such a culmination, at least for now, of what he has been working on since his first album’s “Twilight.” The big difference is that he now possesses a much more formidable understanding of what is to be done with his talent. He plays through each of these pieces with the emotional variety that allows the individual performance to avoid repetition of feeling, technique, and rhythm. The direct but mysterious nature of his work on the title track stands up well when played in the wake of Muddy Waters, as does the writing itself. On “Jig’s Jig,” he brings off what a number of musicians who would address contemporary dance oriented beats fail to do. Marsalis maintains the groove but doesn’t lose the inspired bite that is so often sacrificed for a handful of clichés. “So This Is Jazz, Huh?” is the third track that supplies evidence of his position as a superior inventor of melody. And so he goes, ever moving further into the fundamentals that are so mightily addressed not only in this last third of the Blues Cycle, but throughout the entire collection. Wynton Marsalis’ wings fit him well, and wherever he chooses to fly, the music of jazz will go with him. Soul Gestures In Southern Blue is sufficient proof of that.

–Stanley Crouch

Credits

Art Direction – Josephine Didonato

Artwork – Romare Bearden

Bass – Reginald Veal

Drums – Herlin Riley

Engineer [Additional Mixing] – Mark Wilder

Engineer [BMG] – Dennis Ferrante

Engineer [Chief] – Tim Geelan

Executive-Producer – Dr. George Butler*

Photography By – Frank Stewart (2)

Piano – Marcus Roberts

Producer – Steve Epstein

Saxophone – Todd Williams, Todd Williams, Wessell Anderson

Trumpet – Wynton Marsalis

Written-By – Todd Williams (tracks: 4), Wynton Marsalis

Recorded digitally onto the Sony PCM 3324 Digital Recorder at BMG Studios, New York.

Mixed onto the Sony PCM 1630 2 Track Digital System at Sony Music Studio Operations, New York.

Mastered at Europadisk, Ltd., New York.

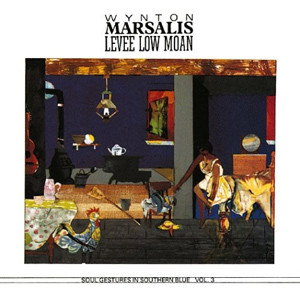

Cover artwork:

Romare Bearden. The Evening Guitar. 1987

Watercolor and collage, 20 × 24 inches.

Estate of Romare Bearden, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York, NY.

Exclusive Personal and Financial Management:

AMG International, P.O. Box 55398, Washington, DC 20011,

Edward C. Arrendell, II/Vernon H. Hammond, III, Partners.

CMU P 99 appears on the clear part of the matrix CD ring.

Copyright © – Sony Music Entertainment Inc.

Phonographic Copyright (p) – Sony Music Entertainment Inc.

Manufactured By – Columbia Records, Inc.

Mastered At – Europadisk

Mixed At – Sony Music Studio Operations

Recorded At – BMG Studios, NY

Pressed By – Columbia Records Pressing Plant, Pitman

Personnel

- Todd Williams – tenor sax, soprano sax

- Marcus Roberts – piano

- Herlin Riley – drums, tambourine

- Reginald Veal – bass

- Wess “Warmdaddy” Anderson – alto sax, sopranino sax

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Jig’s Jig - Wynton Marsalis Sextet at Jazz in Marciac 2015

-

Videos

Videos

Superb Starling - Wynton Marsalis Septet at Dizzy’s Club 2013

-

Videos

Videos

Jig’s Jig - Wynton Marsalis Septet at Dizzy’s Club 2013

-

Videos

Videos

Superb Starling - Wynton Marsalis Septet at Jazz in Marciac 2008

-

Videos

Videos

Superb Starling (rehearsal) - Wynton Marsalis Septet at Jazz in Marciac 2008

-

Videos

Videos

Wynton Marsalis Quintet in Andorra (1988)

-

Photo Galleries

Photo Galleries

Wynton Marsalis Septet at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola (day #4)

-

Photo Galleries

Photo Galleries

Wynton Marsalis Septet at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola (day #3)