Wynton Marsalis, Immersed in the Deep Blues

Some 100 years after its development, the blues and its distinctly American tonality still roll on. The impact has been astounding: a humble 12-bar, 3-chord repeating cycle, made popular by the repressed black minority, has given definition to some of the most important musical developments of the 20th century. With its endless decline and regeneration and its unsettled harmonic pulling and pushing — Europe and Africa in contention — the blues seems to sum up a tumultuous century. It even defines by its absence: popular music without the blues impulse or tonality sounds archaic and limited in expression.

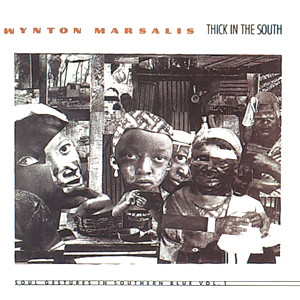

Few jazz musicians have had the audacity or the commercial freedom to tackle the subject as thoroughly as the trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. Mr. Marsalis has just released a three-CD series called “Soul Gestures in Southern Blue,” which is jazz’s largest concept album ever. It is also brilliant music. Other jazz composers have tackled the blues form or mood at LP length — Duke Ellington in “Ellington Indigos” and “Blues in Orbit,” Charles Mingus in “Blues and Roots,” Jackie McLean in “Bluesnik,” Miles Davis in “Kind of Blue” and John Coltrane in “Coltrane Plays the Blues” — but none have had the liberty to put out a nearly three-hour project.

Typically, Mr. Marsalis brings an ideological perspective to the project. “Soul Gestures,” like his previous albums of standards, is meant to recapture the blues foundation of jazz. This is a three-CD set with an argument: in the face of a jazz heterodoxy that allows for improvisation without knowledge of the blues, Mr. Marsalis is saying that without the blues, jazz does not exist.

Each of the three albums takes on a different aspect of the music, and Mr. Marsalis wrote the individual songs as parts of an album-length suite. The first volume, “Thick in the South” (Columbia 47975; CD and cassette), concentrates on the harmonic possibilities of the blues. The second album, “Uptown Ruler” (Columbia 47976; CD and cassette), uses blues ideas within other forms, working more with the blues mood. And the third volume, “Levee Low Moan” (Columbia 47977; CD and cassette), explores the different rhythms generated by the blues.

“Thick in the South” features a quintet with Mr. Marsalis on trumpet, Joe Henderson on saxophone, Marcus Roberts on piano, Bob Hurst on bass and either Jeff Watts or Elvin Jones on drums. “Uptown Ruler” and “Levee Low Moan” spotlight Todd Williams on saxophone, Mr. Roberts on piano, Reginald Veal on bass and Herlin Riley on drums, with the addition of Wessell Anderson on saxophone for “Levee Low Moan.”

Taken together the albums make a case for detailed composition. Where much of small-group mainstream jazz defines its emotional content by just tempo and harmony, leaving the improvisers room to interpret, Mr. Marsalis has kept the composer’s authority throughout his pieces. He has ordered the musical workings of each piece so that the compositions always retain their individual moods.

On a tune like “Elveen,” from “Thick in the South,” Mr. Marsalis has altered the blues harmony and given specific chord voicings and rhythmic figures to the band, drenching the piece in a feeling of suspense. Mr. Marsalis has a painterly vision of the music and uses these continuing controls to dictate the tone and mood. Which doesn’t mean that improvisation has no part: there is plenty of fertile playing, but it is challenged by the constraints of the pieces. This is music that makes standard mainstream compositional techniques seem primitive.

Taken together the albums make a case for detailed composition. Where much of small-group mainstream jazz defines its emotional content by just tempo and harmony, leaving the improvisers room to interpret, Mr. Marsalis has kept the composer’s authority throughout his pieces. He has ordered the musical workings of each piece so that the compositions always retain their individual moods.

On a tune like “Elveen,” from “Thick in the South,” Mr. Marsalis has altered the blues harmony and given specific chord voicings and rhythmic figures to the band, drenching the piece in a feeling of suspense. Mr. Marsalis has a painterly vision of the music and uses these continuing controls to dictate the tone and mood. Which doesn’t mean that improvisation has no part: there is plenty of fertile playing, but it is challenged by the constraints of the pieces. This is music that makes standard mainstream compositional techniques seem primitive.

Mr. Marsalis has shot past the modal masters of the 1960’s, the be-bop masters of the 1940’s and 50’s and landed in the swing era of the 30’s. Or, more specifically, in a province of his own making, where he has borrowed swing-era esthetics and merged them with much of jazz history. The music merges New Orleans and Ellingtonian harmonies with a rhythm section that often owes its oceanic swing to John Coltrane’s 1960’s group. It recaptures a specifically American virtuosity that had almost been lost.

The liner notes seem to indicate that the albums capture the entire range of blues expression, but they really do not. These are late-night blues, scathingly introspective and utterly modern; what he is playing is rarely euphoric or joyous. These blues reach an explosive intensity, but they do it every way except through explosions. They draw on jazz movements and milestones: there are references all through each album to New Orleans music, to modalism, to the Miles Davis-Wayne Shorter pairings, to “Coltrane Plays the Blues,” to Ellington and more. Yet these references are often elliptical. The recordings document a time when Mr. Marsalis went from being a promising student to a master, not only of music but also of the larger implications of his art.

by Peter Watrous

Source: New York Times