Marsalis’s Wit and Anger Evoke Visions of America

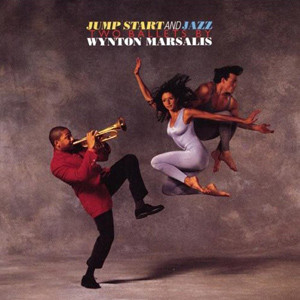

“Jazz (Six Syncopated Movements)” is, true to the New York City Ballet’s habit, a new work for the company that is named after its score. The music is by Wynton Marsalis, one of contemporary jazz’s most popular musicians, and it was written for Peter Martins, one of today’s most prominent neo-classical choreographers.

The premiere of “Jazz,” which the City Ballet presented on Thursday night at the New York State Theater was eagerly awaited for several reasons, not the least of which is the fabulous commissioned score that Mr. Marsalis composed for Garth Fagan’s 1991 modern-dance success, “Griot New York.”

Mr. Marsalis has delivered again, and it would be nice to report that Mr. Martins has matched him, but he has done so only fitfully. In its grand design, this collaboration had rich possibilities, making for a portait of America in the way that Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition” distills the spirit and history of Russia.

Both choreographer and composer here have avoided the literal while drawing from vernacular and historical references in music and dance. But unfortunately each has — as one might say, if this were the 1960’s rather than the 1990’s — gone on to do his own thing.

Mr. Marsalis, knowing how to draw the fine line between pastiche and genuine homage to a musical and social heritage, has produced a composition that is witty or angry, depending on his purpose.

The harshest sound comes in the third section, “Trail of Tears — Across Death Ground,” which evokes the forced removal of the Cherokee Indians from Georgia to Oklahoma in 1838 by the United States Army in a march that left at least 4,000 dead. Essentially a dirge that harks back to the steady beat of a New Orleans jazz funeral, the music becomes something new with the mocking (and thus all the more shocking) laughter that emerges from the muted trumpets in the pit. The score is downright terrific, producing vivid images with sophistication.

Mr. Martins is all sophistication with only sporadic vividness. Unaccountably, his choreography is step-poor for the ensembles, with his movement invention surfacing only in the duets, trios and quartets, which are more illustrative than abstract.

The ballet’s choreographic knockout, therefore, becomes the sexy duet, alternately limp and angular, in Mr. Marsalis’s middle blues section, and that success owes much to sensational performances by Nikolaj Hubbe and Wendy Whelan. There is also a playful rightness to the elbow-swinging syncopated male trio — Arch Higgins, Tom Gold, Alexander Ritter — that backs up Yvonne Borree when the strains of “Three Blind Mice” are heard in a cleverly spliced-in musical fantasy, “Tick Tock — Night Fall on Toyland.”

Choreographically, there is also something to look at in the entwined duets that Heather Watts has with Jock Soto or Albert Evans before she consoles them both and they lift her offstage in a cruciform pose in the “Trail of Tears” section.

Two groups of silhouetted men in ranger hats shove Mr. Evans and Mr. Soto onstage to dance out their ordeal. Each is a favorite Martins dancer, but the fact that Mr. Evans is black and that Mr. Soto is an American Indian is a less than subtle underscoring of a point about persecuted populations. Moreover, the use of implied Christian imagery with Miss Watts as both Virgin Mary and Christ only muddles the historical reference. For all their political correctness, the dance images are simplistic.

Elsewhere, Mr. Martins has mainly fallen back on the standard formulas of his neo-classical style. But when he offers neat symmetrical units in his opening ensemble and finale, the feeling is that the music’s American flavor is is being ignored.

Inspired by Sousa’s music, the first section, “Jubilo — The Scent of Democracy” serves more to introduce the entire cast than to waft in the spirit of the parade ground. After “Tick Tock” and “Trail of Tears,” Mr. Marsalis and Mr. Martins effectively evoke the role of the railroad (mobility, expansion) in America in “Express Crossing — Astride Iron Horses.” A passage for Nilas Martins and Melinda Roy is underchoreographed, and Mr. Martins complements the choo-choo sound of Mr. Marsalis’s music with two chugging lines of dancers. Robert Sadin, a guest conductor, led the Marsalis band in the pit.

The blues duet “ ‘D’ in the Key of ‘F,’ “ followed, with Mr. Hubbe slinking with muscular machismo toward an independent, arm-swinging Miss Whelan, who collapsed in his arms. Somehow both wound up on their knees in an acrobatic embrace. “Ragtime-Syncopated With Style” served as the full-cast finale, played to the hilt by the Marsalis band.

The evening, which also featured superb performances by Darci Kistler and Ben Huys in George Balanchine’s “Swan Lake” and the entire cast in his “Violin Concerto” (led by Lourdes Lopez, Nilas Martins, Ms. Whelan, Mr. Soto) was nonetheless a milestone. It was a worthwhile first collaboration between the artistic directors of two Lincoln Center resident companies, Jazz at Lincoln Center and the City Ballet.

By ANNA KISSELGOFF

Source: New York Times