A Luxuriance of Twyla Tharp

Rather than pay tribute to dead choreographers and composers, import guest stars or rush patrons to a dinner where the flower arrangements are as important as the program, American Ballet Theater opted for a change of pace on the gala scene. Having taken a five-year sabbatical from the company, Twyla Tharp returned in style on Monday night.

Premieres are not new to dance-world benefits. But it is hardly your usual money-raiser when a single choreographer presents three new works, and especially when that choreographer is Ms. Tharp. The entire evening at the Metropolitan Opera House had an extravagantly creative air. One never knows what Ms. Tharp will come up with; here again, her originality emerged in her unexpected choice of movement and music, even tone.

“How Near Heaven,” the program’s centerpiece, which received its New York premiere, is the major ballet of the three and is set to Benjamin Britten’s well known Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge. It is a ballet of sweep and mystery, overcoming its occasional clutter through its very daring. It will be seen throughout the season.

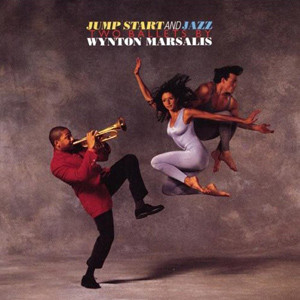

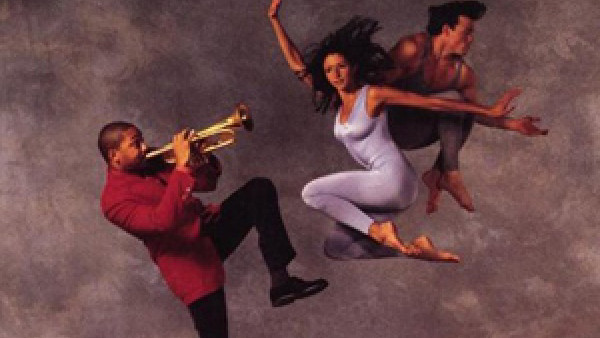

The two world premieres were created as novelties for the gala, with future performances possible in other seasons. Wynton Marsalis and his orchestra were on hand to play the superb score he composed for “Jump Start.” This exuberant piece for dancers in jazz shoes has changed titles (previously called “On the Wing’ ) and has definite possibilities. The opener was “Americans We,” a minor work set to Stephen Foster and other 19th-century American composers; it revs up the audience with its unashamed exploitation of ballet bravura, but eventually drowns in a swamp of sentimentality.

At its best, “Americans We” has the charm of a family photo album; its abstract images echo with joys and sorrows, parade-ground displays, picnics and battlefield tributes. But the ballet’s scrapbook structure also plays to Ms. Tharp’s recent tendency to throw chunks of choreography onstage that shift so sharply in mood that both sum and parts end up as incoherence.

Continue reading the main story

“Americans We” suggests an exercise in mixed metaphors about style and substance. The first group of principals, two couples and a trio, are given classical choreography and the women, in toe shoes, are in Santo Loquasto’s modernized tulle tutus. Suddenly, they become dream figures contrasted with mortals who square dance and wear street dress, led by Michael Owen, a preacher who has escaped from Americana ballets of the 1940’s. Like the protagonist of Jerome Robbins’s “Ives, Songs,” he walks through history and grieves over men who march and die. In this case the war is probably the Civil War, given the 19th-century music (Foster’s “Glendy Burk.)”

This shift between dream and reality is startling but not convincing. And the addition of Susan Jaffe, in white tutu as a cutesy Romantic sylph, is extraneous. To match this fairy godmother, there is Johan Renvall, a ballet godfather who blows away the audience with his brilliant turns and leaps to rousing music that includes marches by Henry Fillmore, a Sousa contemporary.

One might accuse Ms. Tharp of using ballet tricks for their own sake, but they also suggest patriotic fervor, especially when Jennifer Tipton uses red, white and blue in her lighting with the artistry of a color-field painter.

The ensembles and the male choreography show Ms. Tharp at her most inventive. There is a mind-boggling instant when Keith Roberts flies into the air like a piece of twisted metal, his legs crossing over each other in a jete en tournant. Parrish Maynard, a human jumping bean, matches him in energy, when he is not helping Mr. Roberts toss Amanda McKerrow around. Julie Kent and Robert Hill, Christine Dunham and Charles Askegard were given more ordinary choreography.

The score, arranged by Donald Hunsberger, included Paganini’s “Moto Perpetuo,“in a tour-de-force performance by the cornetists Frederick Marcellus and John Hagstrom. David Ripley sang Foster with style.

“Jump Start” also has a suite form and Mr. Marsalis’s sophisticated symphonic treatment of popular music jumps deliberately from genre to genre. Ms. Tharp takes up the challenge, infusing the choreography with the slides and spirals of her own energy-filled idiom.

If the work winds up like one of Ms. Tharp’s teen-age prom pieces, her perspective here is more distant, less literal. “West Side Story” is revisited by finger-snapping figures, virtual cutouts of jitterbuggers. The Latin number starts with Sandra Brown and Martha Butler in a skirt-swishing passage and ends with the ever amazing Mr. Roberts and Shawn Black in a bouncy tango. Mr. Roberts, all high energy, doubles as mock runway model along the way and Isaac Mizrahi’s resort-style costumes are eye-catching. Kathleen Moore, in fact, wears a white bathing suit for her sexy duet with Guillaume Graffin and is also the streetcorner tease with Andrei Dokukin, Mr. Graffin and Griff Braun. Gil Boggs is especially astonishing in his virtuosity.

“How Near Heaven” derives its title from a letter written by Emily Dickinson, an American poet not immune to the works of the English Metaphysical school. Whatever literary subtext Ms. Tharp had in mind, she has constructed a stunning formal work that plays upon the duality of two ballerinas. Ms. Moore and Ms. Jaffe dance with unusual power and are constrasted with a couple who, unusually, have a supporting role.

Cynthia Harvey and Mr. Askegard, as that ideal pair, have ugly aqua costumes by Gianni Versace that match his tacky white bra-topped gowns for the women’s ensemble. By contrast, his gowns for the two ballerinas allow for the astounding ample force in Ms. Tharp’s use of the classical vocabulary here. The Met is too big a house to catch much of the detail that was apparent at the Kennedy Center two months ago: in any case, this is a ballet whose richness will reveal itself fully upon repeated viewings.

by Anna Kisselgoff

Source: The New York Times