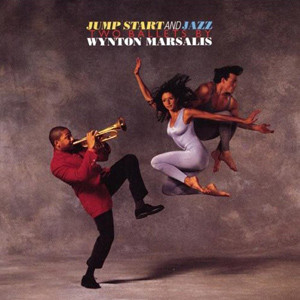

Jump Start and Jazz - Two Ballets by Wynton Marsalis

Several years before Wynton Marsalis wrote his Pulitzer Prize winning “Blood On The Fields,” he was commissioned by the New York City Ballet to write the scores for two original ballets, “Jump Start-The Mastery of Melancholy” and “Jazz: 6 1/2 Syncopated Movements.” These two works were choreographed by Peter Martins and Twyla Tharp, respectively, and their performances met with considerable critical acclaim. On this recording, the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, under the direction of Robert Sadin, performs both compositions with the composer present on trumpet.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Multiple Ensembles |

|---|---|

| Release Date | September 2nd, 1997 |

| Recording Date | January 23, 1993; August 17-18, 1995 |

| Record Label | Sony Classical |

| Catalogue Number | SK 62998 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Jazz: 6 1/2 Syncopated Movements | ||

| Jubilo (The Scent of Democracy) | 4:44 | Play |

| Tick-Tock (Nightfalls on Toyland) | 4:16 | Play |

| Trail of Tears (Across Death Ground) | 7:10 | Play |

| Express Crossing (Astride Iron Horses) | 5:12 | Play |

| “D” in the Key of “F” (Now the Blues) | 5:16 | Play |

| Ragtime | 5:01 | Play |

| Fiddle Bow Real | 2:37 | Play |

| Jump Start - The Mastery of Melancholy | ||

| Boogie Woogie Stomp | 4:13 | Play |

| The Dance | 3:38 | Play |

| Slow Drag | 4:36 | Play |

| Habanera | 2:57 | Play |

| March | 2:51 | Play |

| Gagaku | 3:31 | Play |

| The Spellcaster | 4:51 | Play |

| Bebop | 3:15 | Play |

| Root Groove | 3:51 | Play |

| Jump | 4:23 | Play |

Liner Notes

This splendid music has a dual nature. Jazz and Jump Start are accompaniments, works for hire, tailored not to their composer’s fancy but to the needs of choreographers. Yet they stand magnificently on their own. There’s nothing remarkable about this. One could say the same of Firebird, Appalachian Spring, or The Nutcracker. What is remarkable is the learning curve these two pieces reveal, the rapidity and ease with which their author is shaping himself into a fascinating, perhaps major, American composer: a creator uniquely capable of merging the supple and life-giving groove of jazz with classical music’s formal rigors.

Six years ago, Wynton Marsalis was a celebrated trumpeter and an ambitious but largely untested composer; he had written a few extended works, but only for his own small group. Eager to tackle bigger ensembles, he approached New York City Ballet director Peter Martins about collaborating. In mid-1992, Martins asked Marsalis for a piece that would explore broadly American themes. A few months later, the composer delivered a tape. Martins was dismayed.

“It was completely different from what I expected,” the choreographer says. “I expected a very traditional, conventional view of jazz. What I got was much more, how shall I say, adventurous. I was extremely upset. I remember saying to Wynton, ‘Let’s put this off.’ I was buying time, I had no idea what to do with this music. Then I realized, little by little, that what I had was a terrific, very unusual, very innovative score. And I thought, ‘This is a real challenge, I’m going to have to measure up here.’ I must tell you, this was a remarkable experience for me. This was one of the greatest experiences of my choreographic life. That’s why I’m doing it again”–Martins has commissioned Marsalis’s first piece for symphony orchestra, to be performed in 1999.

Jazz may be Marsalis’s best composition yet–his tightest, at least, his best-built. It rockets seamlessly from start to finish. If its momentum puts one in mind of Petrouchka, that’s no surprise; Wynton played Stravinsky’s great ballet in more than his share of youth orchestras, and composer and choreographer discussed Stravinsky often in their initial talks.

The first movement, “Jubilo,” explodes at the listener, lurching and careening; its’ easy to see how Martins was overwhelmed. Structured like a classic Sousa march, “Jubilo” is crammed with historical, real-world references. On top, the jaunty piccolo evokes the spirit of ’76; in the middle, trumpets and saxophones honk out a funky march in the open, folk harmonies–fourths, fifths, and octaves–of an Emancipation-era black band. These two parts (plus the crisply rolling snare drum) “tie together the notion of freedom, American-style,” says Wynton. “After generations of hardship, suddenly a people can smell freedom. It’s like a bloodhound who’s been on the trail forever and suddenly he picks up the scent. That’s why ‘Jubilo’ is subtitled ‘The Scent of Democracy.’” On the bottom, meanwhile, bass and bass clarinet root things still deeper in the American soil with an old-time fiddle breakdown.

Pieces of this bass line reappear in various slowed-down, sped-up, reversed guises through Jazz: in the flute part in “Tick-Tock,” in the trumpet-piccolo counterpoint halfway through “Express Crossing,” or spread across all the voices in “Fiddle Bow Real.” To these ears, this is the most impressive thing about Jazz: the sly, ultra-economical way Marsalis generates a wealth of material from a few core themes.

The rest of Jazz is less compressed than “Jubilo” but just as striking. “Tick-Tock,” with its coda of sleek, upwardly flowing saxophones, is a quick side-trip away from Americana into the fairy-tale fortunes of a prince, a princess, a troop of soldiers, and an evil, chuckling troll (Wynton’s trumpet, of course). “Trail of Tears” is a gloss on the infamous forced march of the Cherokees. The troll reappears, sniggering at the Indians’ plight. “That’s the irony of tragedy,” says Wynton: “Someone’s not just exploiting you, he’s enjoying it.” Look out–it’s the barrelling transatlantic train of “Express Crossing,” wiping clean the red man’s tracks. “D in the Key of F” is a lovers’ interlude, a sophisticated big-city romance, followed by the celebratory bounce of “Ragtime.” When Jazz premiered in January 1993, Martins hadn’t had time to choreograph Wynton’s finale, “Fiddle Bow Real,” which fleetingly revisits “Jubilo.” So here, for the first time, is the score in its entirety: six-and-a-half syncopated movements. “That was the original title,” says Wynton. “Six-and-a-half, that’s a more syncopated number than six.”

Is Jazz jazz? “That’s a good question,” the composer says. “Even though it has very little improvisation, I’d have to say it’s jazz. It uses the language of jazz and the rhythm section is improvising. That last thing is crucial. You can take away improvisation and something can still be jazz, as long as the rhythm section, especially the drums, is improvising. You’ve got to free the drums if you want that swing, that bodily groove.”

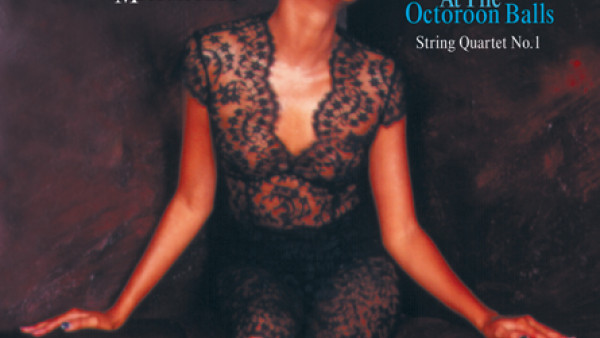

Jump Start has a stronger jazz identity than Jazz, but it’s less of a suitelike whole–choreographer Twyla Tharp asked Marsalis for a string of self-contained pieces, each built around a different dance rhythm, and that’s exactly what she got. Tharp, the most extravagantly gifted American dancemaker of the last quarter-century, commissioned Marsalis’ score in 1994; the ballet premiered the following spring at New York City’s Metropolitan Opera. From the start, this was a lighter, less momentous affair than Jazz.

“I wanted a piece d’occasion to celebrate my thirty years as a choreographer,” Tharp says. “Wynton and I had a couple of talk sessions about the spirit of the thing, which was essentially not to be too lugubrious, not too ‘serious.’ One of the key phrases here, as I recall, was ‘mastery of melancholy’: that we wouldn’t seep into that arena, we wouldn’t go there, and everything would be very much onward and upward.”

The piece jump-starts, as it were, with “Boogie Woogie Stomp,” an infectious thirteen-bar blues with the horns playing dissonant-sounding fourths (not the sort of harmony one usually hears in boogie-woogie music). Wynton composed “The Dance” with Matisse’s pastoral masterpiece “The Dance” in mind. “Slow Drag” is pure Jelly Roll Morton. “It’s got that comic-sad quality you get in a burlesque club,” says Wynton. “It’s the said part of a certain type of tawdry sexuality.”

“Gagaku” is based on the ancient Japanese musical genre of the same name. “I like that music,” Wynton says; “that music has blues in it. I tried to get the brass harmonies to sound like a sho, a Japanese mouth organ.” “Root Groove” is the only programmatic piece in Jump Start. Its sad-sack trombone is a kid who wants to join a playground game, but the other kids/horns tauntingly refuse to let him in. “Jump,” the finale, got a surprise soloist when 81-year-old trumpet star Harry “Sweets” Edison stopped by the studio long enough to kick the music into fifth gear. And Jump Start rocks home, all red-hot horns and pounding backbeat, very much onward and upward.

Wynton Marsalis is clearly fascinated by dance: counting these two, he has now written five ballet and modern-dance scores. Why does so independent a soul willingly subjugate his ego to a bigger cause, harness himself to a collaborator? “Because,” he says, “it gives me a chance to learn something different. If I want to play solos, I can go play a gig. Together, music and dance create something that’s different from either one. It’s better, it’s more, it’s richer. Their audience gets a chance to hear us, our audience gets a chance to see them. The functional aspect of music is real important. Music shouldn’t always be presented on its own. It should lend itself to all types of occasions. It should be part of the landscape.”

Jazz and dance–social dance, that is–were once inseparable, a unity Wynton sorely misses. Indeed, it’s as if he longs so strongly to reunite jazz with its dance-music origins that, lacking the opportunity to play balls, socials and Saturday-night functions, he’s taking the only option available: playing music for choreographed dance. “I would love to play for social dancers,” he says with heat. “Boy, I would love for that to happen.” Until it does, we’ll have to let professional dancers have the pleasure. The substantial pleasure.

“When you have a great musician in your studio,” says Tharp, “and you’re dancing to his music, that’s all you can ask for. That is ultimately what resonates for me, looking back on this experience. Wynton is music. It flows through him. To have that in the same room is a blessing.”

–Tony Scherman

Credits

Jazz: 6 1/2 Syncopated Movements

Wynton Marsalis, Marcus Printup (trumpets)

Ronald Westray (trombone), Wycliffe Gordon (trombone)

Todd Williams (tenor and soprano saxophone)

Wessell Anderson (alto saxophone).

Victor Goines (tenor and soprano saxophone),

Kent Jordan (piccolo, flute)

Eric Reed (piano)

Reginald Veal (bass)

Herlin Riley (drums)

Robert Sadin (conductor)

Jump Start – The Mastery of Melancholy

Wynton Marsalis (conductor, trumpet on “Be Bop”)

Ryan Kisor, Marcus Printup (trumpets)

Wessell Anderson (alto and sopranino saxophone)

Victor Goines (tenor and soprano saxophone)

Ted Nash (tenor and soprano saxophone)

Gideon Feldstein (baritone saxophone and bass clarinet)

Wycliffe Gordon (trombone), Ronald Westray (trombone)

Kent Jordan (piccolo, flute)

Eric Reed (piano)

Ben Wolfe (bass)

Herlin Riley (drums)

Branford Marsalis (soprano saxophone on “Root Groove”)

Harry “Sweets” Edison (trumpet solo on “Jump”)

For “Jazz: 6 1/2 Syncopated Movements”

Producer: Delfeayo Marsalis

Recording/Mix Engineer: Patrick Smith

Assistants: Les Stephenson, Malcolm Little

Technicians: Bill Allen, Minor Little

Recorded analogue 24-Track using Dolby SR – ADD

Piano From Steinway & Sons

Mix Studio: Signet Sound, Los Angeles

Assistants: Drew Webster, Brian Dixon

Mastering: Digital Domain, New Orleans

Editing: Jalmoose

Recorded January 23, 1993, New York City

This was the absolute final recording session ever in the legendary RCA Studio A. The building was sold to the Irs and

vacated shortly after this session. Its presence is sorely missed in the New York acoustic community.

For “Jump Start – The Mastery Of Melancholy”

Producer: Delfeayo Marsalis

Recording/Mix Engineer: Patrick Smith

Assistant: Paul Wertheimer

Technicians: Norm “Buy A Vowel” Dlugatch, Dominic Gonzales

Additional recording: Rob Paustian at TMF Studios

Music Copyist: Ron Carbo

Research Engineer: Willie Jones

Recorded at Paramount Stage M, Los Angeles, August 17-18, 1995

Recorded Digitally (Sony PCM 3348) DDD

Piano From David Abel

Mix Studio: Signet Sound, Los Angeles

Assistants: Drew Webster, Brian Dixon

Mastering: Digital Domain, New Orleans

Editing: Jalmoose

Marcus Printup appears courtesy of Blue Note Records

Wessell Anderson appears courtesy of Atlantic Records

Eric Reed appears courtesy of Impulse! Records

Branford Marsalis appears courtesy of Columbia Records

SK 62998

Art Direction: Allen Weinberg/Josephine DiDonato

Cover Design: Josephine DiDonato

Cover Photos: Lois Greenfield

Exclusive personal and financial management for Wynton Marsalis:

The Management Ark

Santa Fe, NM • Princeton, NJ

Edward C. Arrendeil II • Vernon H. Hammond III

FOR THIS RECORDING 20-BIT TECHNOLOGY WAS USED TO MAXIMIZE SOUND QUALITY. SBM

Personnel

- Marcus Printup – trumpet

- Wycliffe Gordon – trombone

- Ron Westray – trombone

- Todd Williams – tenor sax, soprano sax

- Wess “Warmdaddy” Anderson – alto sax, sopranino sax

- Victor Goines – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet, bass clarinet

- Kent Jordan – flute

- Eric Reed – piano

- Reginald Veal – bass

- Herlin Riley – drums, tambourine

- Robert Sadin – conductor

- Ryan Kisor – trumpet

- Ted Nash – alto sax, soprano sax, clarinet, flute, piccolo

- Gideon Feldstein – baritone sax, bass clarinet

- Ben Wolfe – bass

- Branford Marsalis – tenor sax, soprano sax

- Harry “Sweets” Edison – trumpet

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Accent on the Offbeat - Wynton Marsalis Ensemble featuring the New York City Ballet

-

Videos

Videos

Wynton talking with choreographer Peter Martins about his ballet “Jazz” - Charlie Rose Show

-

Wynton's Blog

Wynton's Blog

In 1992, I wrote a ballet for the fantastic New York City Ballet. One movement had to be a train

-

Wynton's Blog

Wynton's Blog

Creole Contradanzas and Habanera

-

News

News

Jump (full score + parts) is now available

-

News

News

Jazz In Motion: World Premieres by Wynton Marsalis

-

News

News

A Luxuriance of Twyla Tharp

-

News

News

Marsalis’s Wit and Anger Evoke Visions of America