Out of the Comfort Zone, On to New Adventures

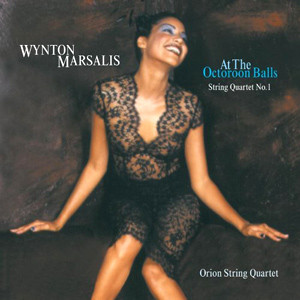

TODAY IN ALICE TULLY Hall, Wynton Marsalis faces one of his toughest challenges yet. And for a while at least, the magnetic jazz and classical trumpeter won’t even be allowed to pick up his horn. He’ll have to sit in the audience with everybody else and face the music, as the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center presents the premiere of his new work for string quartet, “(At the) Octoroon Ball.”

By tackling the venerable quartet genre, Mr. Marsalis, who is the artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, joins the long line of composers who have dared to match wits with the likes of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Bartok and Shostakovich. By inviting him to do so, the Chamber Music Society continues its 25-year tradition of commissioning works from leading composers of all stripes, from Barber to Boulez and beyond, while also browsing through the inexhaustible riches of three centuries’ worth of chamber music.

As it begins its second quarter-century, the society can claim a central role in transforming the landscape of music performance in this country. At the time of its first concert, in September 1969, it represented a novel idea: a “repertory company” of music, in which a core of artist-members could form a wide variety of ensembles for strings, winds or piano, sometimes adding guest artists to extend its repertory even further.

Chamber music presentation on this scale had never been tried in New York or any other American city. There were, of course, plenty of duo concerts, invariably billed as solo recitals, as if the hard-working pianist weren’t there. But what else? Occasionally the “only New York appearance” of a well-known string quartet or piano trio; presentations to small audiences of connoisseurs in neighborhood halls; concerts in the music schools. That was about it.

But the country was on the verge of a boom in chamber music performance. “We were curious,” said the artist manager John Gingrich, whose firm handles a dozen or so chamber ensembles. “We hadn’t heard this music. We had had a long run of the star recitalists, and we had enjoyed a glory period with the orchestra. Then the LP record spread out the whole chamber-music realm for us. I could say to a concert presenter: ‘You know that Tchaikovsky ballet score that you like? Well, wait till you hear his First Quartet.’ “

DURING THE 1970’S AND 80’s, hundreds of touring ensembles like the ones Mr. Gingrich represents sprang up and crisscrossed the nation, delighting audiences in every town or hamlet that could pay their bus fare. And in cities like Chicago, Minneapolis, Houston and Pasadena, Calif., flexible assemblages of players stayed home and emulated the Lincoln Center group, building relationships with their local audiences.

By 1977, chamber music — ensemble music with one player to a part — had become enough of an “industry” to warrant a trade association. That year, a group of concert presenters and musicians formed Chamber Music America to advise ensembles on everything from repertory to travel discounts and health insurance. The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, through its concerts, tours, broadcasts and recordings, said Dean K. Stein, the executive director of Chamber Music America, has been “a model and a force” for the development of audiences and programs all over the country.

In fact, although the society is now celebrating its 25th-anniversary season, it may actually be approaching its 30th, if one traces it back to a gleam in the eye of the composer William Schuman, who was president of Lincoln Center from 1962 to 1969. Determined, as he put it, that the new arts center not be “just a real-estate operation” serving such well-established tenants as the New York Philharmonic and the Metropolitan Opera, Schuman involved it in the founding of new organizations devoted to theater, film, recitals by touring musicians, and chamber music.

In 1966, Schuman gave Charles Wadsworth, a pianist who had organized a chamber series at the Spoleto Festival, the full-time job of working up proposals for chamber-music performance. Mr. Wadsworth had the luxury of time; he sat at his Lincoln Center desk, generating ideas about repertory, budget, organization and personnel, for three years before a note of chamber music was played.

But finally, the center’s new chamber-music auditorium was completed. It was named Alice Tully Hall, after the patron who underwrote its construction and backed the Chamber Music Society from its inception until her death in 1993. Although the inaugural week of three concerts, in 1969, was devoted to the bedrock of European repertory, from Bach to Rachmaninoff, the next concert featured a premiere, “New People,” for mezzo-soprano, viola and piano, by the American composer Michael Colgrass.

In its early years, the society attracted the interest and participation of such musical luminaries as the New York Philharmonic music directors Leonard Bernstein and Pierre Boulez, and the sopranos Victoria de los Angeles and Beverly Sills. A long line of guest artists have since brought not only their box-office appeal but their unique musical knowledge to the society’s concerts.

More valuable even than these visitors, perhaps, was the society’s able front man, Mr. Wadsworth, an ebullient Georgian with a Jimmy Carter grin. His enthusiastic chats with the audience created a comfort zone in which both old and new music could flourish. With its winning combination of national prestige and local goodwill, the society seemed to live a charmed life, cruising from season to season while Schuman’s equally cherished Lincoln Center repertory companies in theater and cinema struggled or failed altogether.

But at what point does comfort become complacency? Inevitably, the society’s easygoing atmosphere — almost like a summer music festival in November — drew fire from some of the more exigent New York concertgoers. Even Mr. Wadsworth acknowledges that by the time he left his post as artistic director in 1988, some changes in personnel and repertory were in order.

The man who made those alterations was Mr. Wadsworth’s successor, the versatile and respected cellist Fred Sherry. Mr. Sherry’s changes in the roster of players and his increased emphasis on new music, a longtime specialty of his, were hardly radical moves, but the society’s audience reacted sharply, cutting the number of subscriptions by 21 percent during his first season. He gave interviews and sought compromise, but in 1992 he decided that his cellist’s chair was more congenial than the executive swivel chair and passed the job to the clarinetist David Shifrin. Mr. Sherry remains an artist-member of the society.

While making the expected adjustment back toward traditional repertory — which includes, in the coming season, a Beethoven festival and a set of vocal concerts in honor of Mr. Wadsworth — Mr. Shifrin also began a “Music of Our Time” series in Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade Theater. It is a sort of Triple-A league of new music, in which emerging composers are exposed to a small but knowledgeable audience, with the possibility of someday joining the likes of Charles Wuorinen, Bright Sheng, Joan Tower and John Harbison on the society’s main programs.

AS THROUGHOUT ITS history, the society builds the chamber-music audiences of the future with school programs, performer and composer apprenticeships, and ticket subsidies for young people, which reach an estimated 6,000 elementary and high-school students each year. As education director, the composer Bruce Adolphe oversees these programs, and he has also stepped into Mr. Wadsworth’s large shoes as the preconcert speaker.

The anniversary season has mixed the new with the old, and as if to emphasize the point, the concluding subscription concerts today and on Tuesday are as open-ended as the opening gala last September was traditional. Not that it’s so unusual anymore to hear jazz-inspired chamber music by Ravel, Gershwin and Stravinsky, but the Marsalis premiere and some improvisations on jazz standards by Mr. Marsalis and the pianist Marcus Roberts will add a touch of the unpredictable to this celebration of two chamber-music traditions, one European in origin, the other African-American.

Such are the ideas with which a 25-year-old institution keeps itself fresh. But perhaps the most important fact about the Chamber Music Society is that it is an institution, not an itinerant ensemble, and was designed to be one from the start.

“What Wadsworth, Schuman and Tully did,” Mr. Gingrich, the artist manager, said, “was to institutionalize the idea that you should listen to chamber music regularly as part of your balanced performing-arts diet.” And whether it’s meat-and-potatoes or sushi, the society still serves it with a smile.

By David Wright

Source: The New York Times