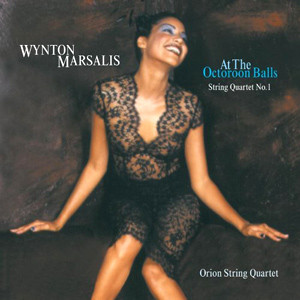

At The Octoroon Balls - String Quartet No. 1

The first part of this CD features the Orion String Quartet’s performance of Wynton’s first string quartet, AT THE OCTOROON BALLS, which explores the American Creole contradictions and compromises – cultural, social, and political – exemplified by life in New Orleans. The piece’s seven movements evoke people, places, and events in the Crescent City: “Come Long Fiddler,” “Mating Calls and Delta Rhythms,” “Creole Contradanzas,” “Many Gone,” “Hellbound Highball,” “Blue Lights on the Bayou,” and “Rampart St. Row House Rag.”

The CD concludes with a performance by Wynton and members of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center of his composition A FIDDLER’S TALE, a response to Stravinsky’s famous A SOLDIER’S STORY from the perspective of later twentieth century music, including but not limited to jazz.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Multiple Ensembles |

|---|---|

| Release Date | June 15th, 1999 |

| Recording Date | December 8-9, 1998; May 11-13, 1998 |

| Record Label | Sony Classical |

| Catalogue Number | SK 60979 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Classical Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| At the Octoroon Balls - String Quartet No. 1 | ||

| Come Long Fiddler | 9:44 | Play |

| Mating Calls and Delta Rhythms | 5:30 | Play |

| Creole Contradanzas | 5:00 | Play |

| Many Gone | 8:56 | Play |

| Hellbound Highball | 8:21 | Play |

| Blue Lights On The Bayou | 2:33 | Play |

| Rampart St. Row House Rag | 4:48 | Play |

| A Fiddler’s Tale Suite | ||

| The Fiddler’s March | 3:27 | Play |

| A Fiddler’s Soul | 3:15 | Play |

| Pastorale | 4:12 | Play |

| Happy March | 2:24 | Play |

| Concert Piece | 3:07 | Play |

| Tango, Waltz, Ragtime | 7:29 | Play |

| The Devil’s Dance | 2:37 | Play |

| Big Choral | 2:48 | Play |

| The Blues On Top | 2:26 | Play |

Liner Notes

America is a hothouse of hybridity; and the very title of Wynton Marsalis’ strong work for string quartet suggests that its subject is hybridity. The balls that give their name to these stringent, voluptuous movements were institutions of old New Orleans, at which Creole men chose Octoroon women for their mistresses–vivacious rituals of mixture, in which the terribilities of race collided jubilantly with the terribilities of sex. It was a universe in which mixture was destiny; a universe in which misery and malaise were justified by a preposterous ideal of purity. And the apparent hybridity of At the Octoroon Balls is not only a historical matter. For this is the first “classical” composition for strings by a master of jazz: a mixture! The musical genres, too, seem to have exceeded their boundaries, and to have run into each other like sauces on a steaming plate. Is the piece “classical”? Is the piece jazz? No, it is another compound in a country of compounds; and blessed are the compounded in America.

Or so it would appear. In truth, however, there is nothing octoroonish about At the Octoroon Balls. Marsalis’ work is in no sense a hybrid. It is not a bit of this and a bit of that; not an arithmetical sum of ingredients and influences; not a crossover contraption of any sort. It is, un-anxiously and unapologetically, itself: a composition for four string instruments in seven movements based upon vernacular American materials. And there is a lesson for American culture in the absence of anxiety and apology from Marsalis’ work. The lesson is that the new American obsession with hybridity is just the obverse of the old American obsession with purity, and it is just as depleting of the spirit.

Like the ideal of purity the ideal of hybridity bows before the tyranny of origins, and prefers authenticity to art. But surely the question, “Where does it come from?” is not as primary as the question, “What is it?” The latter is certainly more difficult to answer than the former. It requires that one look with rigor, listen with rigor, and think with rigor; whereas establishing the provenance of an idea or an image or a theme–fixing the bloodlines of art–is much less strenuous. Art does not possess identity. Art possesses beauty and meaning. This is sometimes hard to grasp in an America addled by identity.

Like the ideal of purity, the ideal of hybridity represents a vexation about legitimacy. Americans are always wondering whether works of art are legitimate. (Is it jazz? Is it “classical”? Is it high? Is it low?) But if a work of art lives, I mean really lives, then, it is legitimate. And if it does not live, then all the legitimacy in the world will not give it life. Life settles the matter. So the task for the American artist is not purity and it is not hybridity. The task for the American artist is integrity.

Integrity is an attitude toward mixture–a morality of mixture. According to this morality, disparate elements must be combined into a unity in a manner that dose not subdue them but does not revere them, so that something new can be created that cannot be reduced to its sources. Such a combination is not merely additive, as in the grotesque racial biology of the recent dark ages. In an undated and unpublished essay on “The Americans,” Jean Toomer denounced the coercive classifications and the dogmatic divisions. “There is a new race here,” he observed about the United States. “For the present we may call it the American race…and though to some extent, to be sure, black and white and red and brown strains have entered into its formation, we should not view it as part black, part white, and so on…Water, though composed of two parts of hydrogen and one part of oxygen, is not hydrogen and oxygen; it is water, a new substance with a new form.”

Toomer’s scruple about the complexities of America holds also for the complexities of art. For all genuine art is of mixed stock. In art, impurity is a kind of felicity; but this felicity must not be described merely as hybridity, or the miracle will be missed. Out of old substances, a new substance. Out of old forms, a new form. Blend, blend. Transmute, transmute. The important thing is not to trap beauty in history.

Marsalis writes out of a profound conviction of the naturalness of American themes and American forms. This is a string quartet saturated in the blues. Its mysterious opening strains–like the first rays of light on an uncertain day–quickly issue in a piquant, fractured country dance that leaves one imagining Bartók in the Delta. The violin sounds like a fiddle, the fiddle sounds like a violin: Marsalis is uninhibited by the dichotomies. (So is the Orion Quartet, to judge by its achievement on this recording.) Its fifth movement is a furious scherzo, based on the diabolical propulsion of trains, the great symbol of American energy, and of the speed with which fortunes and directions are reversed in this exacting land of opportunity. Its final movement is a delightful rag, within which there takes place a friendly disputation between sophistication and well-being.

It was a rag that got Dvořák into trouble. “The influence of Dvořák’s American music has been terrible,” carped an influential critic in New York in 1893, in the wake of the New World Symphony. “Ragtime is the popular pablum now. I need hardly add that the Negro is not the original race in our country. And ragtime is only rhythmic motion, not music.” This was not only moral idiocy, it was also musical idiocy. What had provoked the critic was Dvořák’s championship of “what are called the Negro melodies.” Those melodies, the Bohemian composer had asserted to a newspaper, “are American. They are the songs of America and your composers must turn to them. All of the great musicians have borrowed from the songs of the common people. Beethoven’s most charming scherzo is based upon what might now be considered a skillfully handled Negro melody. I have myself gone to the simple, half-forgotten tunes of the Bohemian peasants for hints in my most serious work.”

Dvořák was hoping to talk his American hosts out of their insecurity about their own patrimony, to persuade them of the adequacy of their own riches. As it happened, European composers proved more hospital to the demotic sounds and colors of America than American composers; but the discussion that Dvořák started a hundred years ago still continues. In that discussion, certainly, At the Octoroon Balls is a significant expostulation. Marsalis’ composition for strings is admirable not least for its cool, easeful Americanism.

This Americanism is not a matter of patriotism. It is a matter of one’s presence to one’s own reality, to the plenitude in which one finds oneself. Reality is not elsewhere. The plenitude is everywhere. And the plenitude is always parochial, because it is always discovered in a single parish. Is a single parish too small? Not for a serious and toiling soul. The universal is the gift of the local. For a serious and toiling soul, the gaiety and the melancholy of a ball in New Orleans will suffice. He will coax art out of the confinement, out of the old dance of injustice and desire.

Leon Wieseltier

Credits

“At The Octoroon Balls (String Quartet No. 1)”

Orion String Quartet

Daniel Phillips (violin), Todd Phillips (violin), Steven Tanenbom (viola), Timothy Eddy (cello)

“A Fiddler’s Tale Suite”

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet)

Musicians from the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

David Shifrin (clarinet), Milan Turkovic (basson), David Taylor (Trombone), Ida Kavafian (violin), Edgar Meyer (bass), Stefon Harris (percussion)

At The Octoroon Balls was commissioned by The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center for Jazz at Lincoln Center and premiered on May 7, 1995 at Alice Tully Hall by the Orion String Quartet. A Fiddler’s Tale was commissioned by The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center for MARSALIS/ STRAVINSKY: a joint project of The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center and Jazz at Lincoln Center.

It was premiered on April 23, 1998 at Hill Auditorium in Ann Arbor, MI.

The complete version of A Fiddler’s Tale with narration by the award-winning actor Andre De Shields is also available on Sony Classical (SK 60765).

The Management Ark

Santa Fe, NM – Princeton, NJ

Edward C. Arrendell II – Vernon H. Hammond III

Producer: Steven Epstein

Recording & Mix Engineer: Richard King

Assistant Engineer & Technical Supervisor: Jeff Francis

Editing Engineers: Robert Wolff,Todd Whitelock

DSD Engineer: Gus Skinas (Tracks 1-7)

This CD was recorded utilizing Sony’s DIRECT STREAM DIGITAL™

(DSD) System (Tracks 1-7). For this recording, 24-bit technology was used to maximize sound quality (Tracks 8-16).

Recorded at Giandomenico Studios, Collingswood, NJ on December 8-9, 1998 (At The Octoroon Balls – String Quartet No. 1) and May 11-13, 1998

(A Fiddler s Tale Suite).

Product Manager: Lisa Stevens

Editorial Direction: Richard Haney-Jardine

Art Direction : Josephine DiDonato

Cover Photography: Kip Meyer

Recording Session Photos: Waring Abbott

SK 60979 Total Time: 76’42

© 1999 Sony Music Entertainment Inc. © 1999 Sony Music Entertainment Inc.

Personnel

- Daniel Phillips – violin

- Todd Phillips – violin

- Steven Tenenbom – viola

- Timothy Eddy – cello

- David Shifrin – clarinet

- Milan Turkovic – bassoon

- David Taylor – trombone

- Ida Kavafian – violin

- Edgar Meyer – bass

- Stefon Harris – vibraphone