Wynton’s Decade: Creating a Canon

Ten years ago, young players in crispy pressed suits were not yet being signed by major labels; Lincoln Center in New York was not yet presenting an 11-month jazz season; the Ravinia Festival near Chicago had not yet begun its ground-breaking Jazz. In June series; nightclubs in Chicago, Los Angeles, Manhattan, New Orleans; and other musical centers were not yet drawing young listeners previously hocked on the relentless backbeat of rock & roll.

Though no single musician deserves full credit for these developments, there seems little question that Marsalis has been essential in igniting them. Along the way, he has been celebrated, criticized, lionized, vilified, televised, and endlessly analyzed.

For Marsalis, who first appeared on DB’s cover 10 years ago this month, it has been a most volatile decade.

“Man, the scene has changed a lot since then, definitely,” says Marsalis, referring to his first days as a leader, in 1982. “When we first came on, we were fighting just to play jazz, on any level – just to play it. Just the whole philosophy of playing it was considered strange. It seemed like so many people [in the music business] were bowed down before rock music, before the altar of rock. That was the struggle, and that was the source of a lot of the problems we had. In the beginning it was rough.

“And then it was always written that I was against rock music and against pop music, which really wasn’t true – it was just that I was trying to see it put in prowir perspective. And the whole question of whether we wore suits and all of that – now I’ll show you pictures of when I was growing up, we never had suits at home. It wasn’t a matter of making a social statement, even though some people were trying to tie it in with Ronald Reagan and all that stuff about conservatism. That was totally ridiculous.”

How times have changed. Younger artists – such as pianist Marcus Roberts, trumpeters Roy Hargrove and Marlon Jordan, the Harper Brothers band, alto saxophonist Christopher Hollyday, and scores more – now routinely sport the sleek garb and musical traditionalism that years ago were among Marsalis’ trademarks. And when Lincoln Center unveiled its sweeping jazz program roughly two years ago, its choice of Marsalis as artistic director was no surprise.

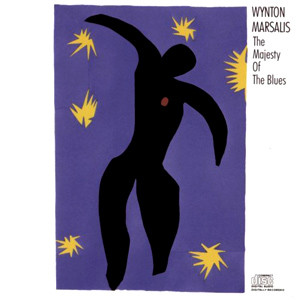

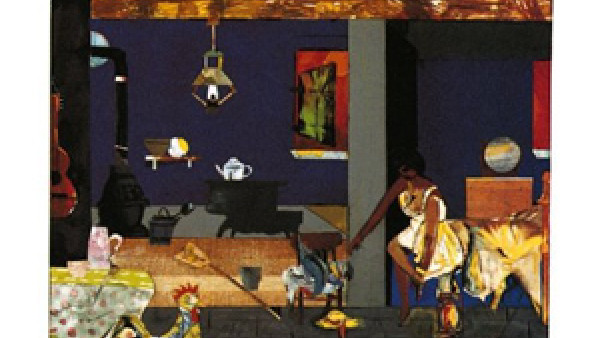

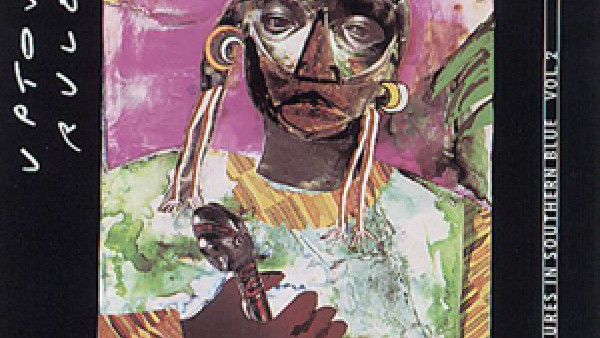

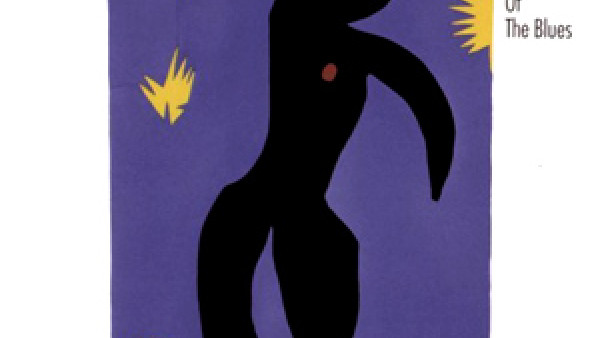

Most important, Marsalis’ music has grown well beyond his technically strong but artistically derivative work of the early ’80s. In the past few years, he has yielded recordings of remarkable substance and originality, beginning with the incantatory Majesty Of The Blues (released in 1989), and followed in remarkably quick succession with his propulsive soundtrack for the film Tune In Tomorrow (1990), his profound study of New Orleans idioms in the CD trilogy Soul Gestures In Southern Blue (1991), and his fiercely modern tone poem, Blue Interlude (1992).

Recorded – but not yet released – is his nearly two-hour evocation of gospel idioms, In This House/On This Morning (1992), and an urban portrait created for and performed with the Garth Fagan Dance company, titled Griot New York (1991). His latest magnum opus is a six-movement score to be danced to by the New York City Ballet in January.

For Marsalis, the turning point that transformed an aspiring artist into a leader took place in one of the foremost jazz “schools” of all, the Art Blakey band of the late ’70s. “Art Blakey was always open to different ideas – he would check out what you were saying,” recalls Marsalis. “In fact, the reason he could always get good [young] musicians in his band was his talent for being able to listen for what you were doing instead of what you weren’t doing.

“And the reason I started wearing suits also was because of Art Blakey’s band, because we would be playing in overalls, and I was embarrassed, man. I was thinking, ‘I’m not standing up here with the great Art Blakey playing in overalls.’ So I said, ‘Look, man, tomorrow I’m coming to this gig with a suit on.’ And I went out and got a polyester suit. I didn’t have any real style, so I got this gray polyester three-piece deal, a maroon tie, and a derby. I still remember that suit. And after that we started getting clean. For us, it was a statement of seriousness. We come out here, we try to entertain our audience and play, and we want to look good so that they can feel good.

“Or maybe,” jokes Marsalis, “maybe we felt that even if we don’t sound good, at least we look good. But it wasn’t calculated. I never knew what the response to any of what we were doing was going to be. I was new to all that publicity, man, and I didn’t know anything about that. I was just trying to play trumpet. But Art said it was a good idea. He said, ‘Yes, it’s time to get clean again.’”

Because Marsalis’ early work as a leader owed a debt to Miles Davis’ great mid-‘60s quintet, Marsalis found himself often compared to Davis, not often favorably. At the very least, an uneasy relationship emerged between the two musicians. “He and I, we knew each other well,” says Marsalis. “And the stuff in the media [about our relationship] was just the stuff in the media.

“Because his music had a profound impact on me as a musician. And he knew this, because he and I would sit down and talk, and we would discuss all of his music – I mean the music that he was really seriously playing. But, then again, he made things more difficult for me, because I was trying to build jazz up, and represent it, which he had represented so magnificently when he was serious.

“But unfortunately, by the time I came around, he had bent over so far for rock & roll that he was a hindrance. Like I would go to jazz festivals, and he would be there playing rock music or funk or something – he was always saying something negative about jazz music. And he could always be held up by the opponents of jazz as some kind of an example. He was like a great general who goes over to the other side.

“So you respect his achievements when he was a great general, but he put me in a strange position, because I had to deal with representing the music and yet not turn it into anything personal [between us]. I was very sorry over his death, of course, but I can’t say that I supported his positions. “See, he did abdicate his position, but it wasn’t like he was being forced out. It wasn’t like a Louis Armstrong-King Oliver situation, where I was playing so much horn that it scared him or any of that. I was trying to play; and he wasn’t, so we never had that kind of a competition. And I don’t have any problem accepting the leadership of elders – that’s not a problem with me.”

By the mid-‘80s, Marsalis found himself forced to make a choice. Because he had won classical and jazz Grammys in both ’83 and ’84, he was being tugged at by both worlds, in demand in both settings. “I couldn’t keep doing both,” Marsalis once told this writer. “I was playing concertos every night, and sometimes I would be nervous, unless I had been on tour for three or four months and had gotten used to it. “It takes a lot to develop as a jazz musician, and I couldn’t find the time to keep my classical technique up. Finally, given the choice, I had to take jazz, because it’s what attracted me to music in the first place.

Perhaps it was that decision, plus the years of constant touring and recording, that enabled Marsalis to finally find his own voice. After releash1g the Grammy-winning Marsalis Standard Time (the first of three Standard Time recordings) in 1987, Marsalis went into the recording studio to put down the music that would be released as Majesty Of The Blues and the Soul Gestures In Southern Blue trilogy. Both explore historic forms – marches, dirges, blues, parade music, etc… – and were imbued with contemporary harmonies and a lean, distinctly modern point of view. They were fervently lyrical recordings, and they proved that Marsalis had found a personal kind of inspiration in the music and atmosphere of his birthplace, New Orleans.

“They came out as one album [Majesty] and three albums Soul Gestures, but I really thought of them as a four-album set,” says Marsalis.’ “And it came out of a desire to really address the broad range of blues music, because that’s what I felt we needed to deal with in our generation, to really get a good centering.

But not to just try to play folk blues, but to use the elements of the blues and deal with the fundamentals, from a contemporary standpoint.

“See, the big thing was, really, when Herlin [Riley, the drummer] and Reginald [Veal on bass] joined, because the rhythm is the heart of a band. Herlin came from the New Orleans tradition, and Reginald wanted to play that kind of music, and Marcus [Roberts] wanted to play like this, too.

So the whole statement of those albums was that we were just trying not to be in any one time [period, stylistically]. We were trying to say that it’s not a matter of the time, because jazz music is perpetually modern.

The history of jazz music is not supposed to develop like European music is. Everybody just takes for granted that you’re supposed to, every year, have some new trend to stack on top of everything else. “But what if the earliest music stays modern, which is the case in jazz music. And it evolves through a certain type of individuality. Like when we play New Orleans music today, it doesn’t sound like when the older musicians played it. But it still has some joy and the same type of optimism. So Majesty Of The Blues is real modern music. Nothing had really been done like that, because it also uses funk music. The bass vamp is a funk vamp. But the groove comes something else, and then there is the blues. The Death of Jazz’ [track on Majesty Of The Blues] is straight blues, like New Orleans call & response, the triads like in the church, like gospel music.”

Different in the best sense of the word, for what Marsalis’ group was playing and recording sounded like no one else. The audaciously bent pitches and incantation-like ostinatos of Majesty Of The Blues, the crying blue notes of “Levee Low Moan,” the church harmonies of “Psalm 26,” the sultry ambience of “Thick In The South” (all from Soul Gestures In Southern Blue), all recalled different settings and epochs in New Orleans music. And yet, the tautness of Marsalis’ septet, the economy of the motifs and the adventurousness of the harmonies proclaimed this as new music, as well.

At the center of this sound was an intense, long-lined lyricism that now graced almost everything Marsalis was playing. The fervency of his melodic line instantly distinguished him from every trumpeter of his generation.

“Sometimes I just like to play a straight melody, something that might seem corny to somebody else,” says Marsalis. “Like on Standard Time Volume 3, with my daddy, I wasn’t trying to play a lot. I just wanted to play the melody, to learn how to play a really good melody. But, then, sometimes I really want to embellish a melody and play fast, like a saxophone. And other times I just want to play quarter notes, like a trumpet, to put it into another context, and not to play in a style. That’s the one thing I don’t want to do.

“I don’t want to be a bebop trumpeter or a swing trumpeter or a New Orleans trumpeter. I want to really try to address the trumpet, period. If it’s baroque trumpet, if it’s Hindemith trumpet sonata, whatever.”

At roughly the same that Marsalis was establishing his voice as composer, in the late ’80s, he was finding another creative outlet as well – Jazz at Lincoln Center.

“The ideas was really to establish a base to get pertinent information about the music out to a wider range of people,” says Marsalis, who serve as artistic of a program jointly steered by Director Rob Gibson and artistic consultant Stanley Crouch and Albert Murray.

“And the belief that a place like Lincoln Center means that the soul is gone from the music or it’s going to be like a museum piece or is a repertory band – that’s just not true. It’s just another setting , and what better setting than a place where the other arts are being celebrated? Like jazz is supposed to stay in Lulu White’s House?”.

As for Jazz at Lincoln Center, the 1992-1993 season has 11 overlapping subscription packages, including theme series on Classical Jazz (music of Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, etc.) New Orleans Legacy (music of Jelly Roll Morton and Johnny Dodds), and Jazz on Film, among others.

“What we’re essentially trying to do is create a jazz canon,” says Jazz at Lincoln Center Director Gibson. “I would define a canon as a representative anthology of jazz creation. And I believe after 100 years of jazz, and with this country being 220 years old, the country is ready to deal with its own history and music.

“In 1960, there was a committee – including Dr. Billy Taylor and Gunther Schuller – that wanted to have jazz in Lincoln Center, but it was rejected. Why, I’m not exactly sure. But I think the thing that changed more than anything, and made it possible for this program to happen,” adds Gibson, whose program has a budget of $1.8 million, “was that in 1987 there was a guy who could play on trumpet a Haydn concerto with a symphony orchestra as well as anyone else could, then take a cab to a club and play with Art Blakey. So Wynton has had a whole lot to do with making something like Jazz at Lincoln Center possible.”

For future seasons, Marsalis hopes to “try to get more of the community involved in the music. We already have a couple of outreach concerts, we play in the different ballrooms of Manhattan. We have long-range goals – things like a competition for bands, an outreach program to the high schools, a picnic with jazz people coming out and having maybe a sweet-potato pie contest – just to let people get in touch with the music. We might have a Duke Ellington contest, in which high school bands would play his music. We haven’t planned it yet, but it’s a possibility.

“We want to continue having Latin music, maybe commission some music. We want to get the most modern music in Lincoln Center, too. So, mainly, we want to codify information on the music and present it, through radio shows, through video releases under the banner of Lincoln Center.”

Along these lines, says Gibson, all the Lincoln Center jazz programs are being taped for potential broadcast and distribution. And lest anyone consider these pipe dreams, it’s worth nothing that Jazz at Lincoln Center has brought Marsalis’ label, Columbia Records, into the picture. The label just released Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra: Portraits By Ellington, and “that’s just the first of a series of recordings we’ll be doing in association with Jazz at Lincoln Center,” says Columbia executive Kevin Gore.

To Marsalis, all this activity is part and parcel of educating listeners, especially young listeners, to the meaning of jazz. For years, Marsalis has been going to the schools, coaching, teaching, lecturing, and trying to inspire youngsters.

He finds that the kids “are hungry to learn, but we need curriculum, we need a canon, we need to find ways to get the school boards interested in seeing that American culture is taught,” he says. “It’s just a growing process, and we have to go from the complaining stage to the stage of action.

“You know, I’ve complained for a long time. I’m tired of complaining. It’s time for us to get into the schools and take control of the situation. When I see teenagers, what I see is undeveloped potential. In general, young people are looking to find themselves. They’re trying to develop their sexuality, they’re trying to determine what kind of an adult they want to be. But young people really want adults to provide them with a direction. So if you come in trying to do a poll of what the kids like, that’s no good. “I believe in what Art Blakey and my daddy and Alvin Batiste and all my teachers represented to me – adult figures, so that you tried to be hip enough to address them.

They weren’t trying to act like you. And me and my brothers could make more money in high school than my father could make on gigs. We made $100 a night playing funk, and he was making $35 or $40 on gigs. But we never had the impression we knew anything about music next to him, and he never gave us that impression.”

To Marsalis, the recent, heightened activity in jazz – Jazz at Lincoln Center, the Columbia Records projects, the proliferation of new artists – suggests “a movement that’s just beginning, a movement to recognize the American arts, and to recognize that the arts have actually put us in greater contact with what it means to be in a democracy. Jazz is a democracy, because jazz is, number one, the willingness to swing.

“And swinging is a matter of coordination, and the coordination means that you are willing to communicate with other people. That’s how swinging is – you get three or four people together, and the only way they can swing is if they work together. And that’s what democracy is – freedom of expression that elevates everybody.

“And that’s why the people are ready for this music. Everybody wants it, they’re ready for change, and they’re ready for positive change, and they’re ready to start trying to get together. They’re tired of fighting each other, they’re tired of being white and black. “People are ready to be Americans, and that’s why it’s time for jazz.”

by Howard Reich

Source: Downbeat