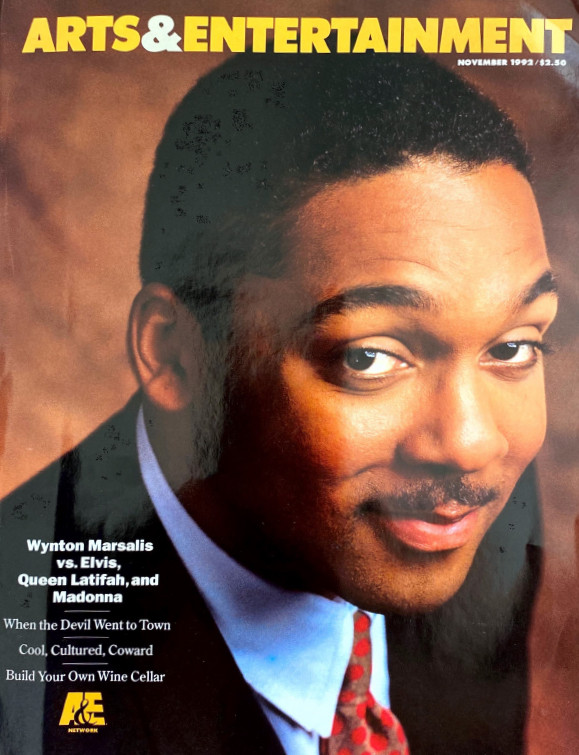

Wynton Marsalis Versus Elvis, Queen Latifah, and Madonna

Cover image: Arts & Entertainment (November 1992)

Every twentieth-century generation has had a jazz trumpet player to call its own. The twenties had Louis Armstrong, the forties, Dizzy Gillespie, and the sixties, Miles Davis. For the 1980s and into the ’90s, Wynton Marsalis occupies that position. Since blasting onto the scene at 18 years of age with Art Blakey’s acclaimed band, the Jazz Messengers, in the late 1970s, he has become emblematic of the young players who take jazz seriously.

The men and women of Marsalis’s age are a funny lot. Where their parents believed in stocks and savings accounts, they begot the get-rich-quick, high-risk, high-gain world of junk bonds. “Instant” is the buzzword that qualifies pretty much anything of value to them. Wynton Marsalis finds this situation disquieting, particularly as it affects music.

“There just weren’t that many musicians in my generation, or in the generation before mine, that really were serious about playing jazz,” remarks the New Orleans-born horn player. “It was an unnatural situation that lasted for 15 years, because of fusion, because of the degenerative philosophical direction that had been assumed by the previous generation. It was based on the principles of immediacy. It’s like making an investment. You can make a sound investment or you can make an unsound investment. I tell kids all the time, when they come to me and ask how they can get some connections and how they can have a hit, ‘You might be able to make it doing that, but your soundest investment would be to go to the practice room and get some lessons. Try to invest in music.’”

This attitude has made Marsalis a favorite among both players and listeners. From early on, his talents were evident, and not only to the late Art Blakey. In the early 1980s, noted jazz keyboard player Herbie Hancock recognized Marsalis’s potential and took him on tour with his VSOP Quartet while on hiatus from the Messengers. As he matured before the eyes and ears of the jazz establishment and jazz fans, he gained respect and followers.

“Wynton Marsalis is the best thing to happen to this music in a long time,” opines legendary jazz singer Betty Carter. “He’s the reason we have so many young players out here. He’s encouraged them, given them something to look forward to. He’s inspired them, and I’m really proud of him. He’s a godsend. Giants in this business defected. They decided, ‘Who cares about this music? Let’s go over here and make some money.’

Then along comes Wynton Marsalis, saying all the right things the young players need to hear, and doing all the right things the young players need to see as far as education is concerned, coming up with great ideas and backing up everything he’s talking about.”

“She said that?” the soft-spoken horn player asks in the earnest tone of a schoolboy who hears a favorite teacher praise him. “Oh, man! I love her. That makes me feel good.”

The 32-year-old Marsalis actually has a lot to feel good about. He has almost singlehandedly brought jazz into a sharper, higher focus than the music has enjoyed since the swing era. Ironically, the new interest in this unique American art form stems not from the pop audience, as it did during the swing era when jazz was the music of choice. Instead, it comes from the classical music audience. Marsalis himself now serves as Artistic Director of Jazz Programming for New York’s Lincoln Center, home to the Metropolitan Opera, New York City Ballet, and the Juilliard School of Music (his alma mater). Since his arrival, both the budget for jazz and the amount of jazz played at Lincoln Center has grown dramatically.

“Jazz is an extension of classical music,” says Marsalis, voicing a conviction that flies in the face of those who would trace jazz exclusively through the blues. “I find that a lot of the early jazz musicians studied classical music. Even musicians like Louis Armstrong learned out of method books. A lot of the lore that celebrates this type of music has it that they just picked the horn up and they could play. Very few musicians could do that. Whenever Louis Armstrong talked, he always referred to musicians he learned from. The method books for the trumpet have been around for a long, long time. I don’t know why there is this impression out there that these guys didn’t have access to this information. They did, and it’s obvious by their level of technical achievement.”

This piece of misinformation, that if you can’t just pick up a horn and blow magic then you’ll never play jazz, is one of Marsalis’s pet peeves. He comes from an exceedingly musical background. His father, Ellis, is one of New Orleans’s best-respected pianists and teachers. One younger brother, Delfeayo, has produced dozens of jazz records and recently released his debut album playing trombone. His immediately junior sibling, Branford, added the position of Tonight Show music director to his already considerable resume as both a sax player and actor. Youngest brother Jason, at 16, is a budding drummer.

So if none of these men, obviously blessed with supermusical genes, could get away without lessons and practicing, no one can. On one level, the myth of the “instant musician” affects Marsalis personally. He has recorded 16 albums of jazz as a band leader, most recently Blue Interlude, with its extraordinary 37-minute long title track. In the process, he has won six Grammy awards. He is also the featured soloist on nine “classical” albums, with two Grammys under his belt for them. None of this came easy and he doesn’t want anyone to think it did. The success he has enjoyed as a professional player for nearly half his life directly results from spending huge portions of his first 18 years – and considerable parts of the last 14 – “in the woodshed,” that is, practicing.

“I always believed in shedding,” he insists. “I shedded for six or seven years before I came out.” On another level, this myth about jazz players of the past affects the jazz players of the future. For many of today’s would-be musicians, the idea of something that delays gratification – like practicing – is alien. In a musical environment where a kid with a drum machine and a knack for rhyme can earn millions, it is the rare person willing to go through the hard steps of the method books. Yet it is only after years in the shed, after thousands of hours of hard work and sweat, that a player can sound like a Miles Davis or a John Coltrane.

“Music became more of a social discussion, like what neighbourhood somebody was from, what kind of hat they wore,” Marsalis points out about the music scene over the last two decades. “Things that didn’t really have anything to do with music. The haircut bands, all these guys who . wanted to imitate rock music felt they could make more money doing that.”

Marsalis contends that these forces have led to the “de-evolution” of American pop, a belief that has become both a philosophical hobbyhorse and a dilemma in his work. The standard jazz repertoire leans heavily on the music that was popular in the ’30s, ’40s, and early ’50s. The rock generation pretty much rejected this music out of hand. Marsalis himself admits that if he were playing the popular music he grew up on, his repertoire would run toward ’70s soul and funk bands like Earth Wind and Fire and Parliament.

The problem is, there’s nothing in that whole canon of music that’s on the level of George Gershwin,” he laments. “You could do [the Parliament hit] ‘Flashlight,’ but do you think that the nature of your statement is going to be the same as playing on a song like ‘Body And Soul’?

Those two songs have an entirely different connotation. They are also the product of a different mentality and reflect different levels of musicianship. I mean contemporary pop songs aren’t even melodies, man. It’s like something you would envision cavemen doing. You can go back to the very earliest forms of American music, and it doesn’t sound that elementary. I’ve been saying this for ten years and getting attacked for it, but that’s what the truth is. When stuff sinks to a certain level, anybody who is concerned about the society has got to say, ‘Wait a second,’ regardless of what’s said or who gets mad or whose feelings get hurt. You can be viewed as a crackpot, but when people start telling me that James Brown is just like Duke Ellington, I have to say ‘Hold on a second. That’s not true.

There’s a huge difference between the two of them, and that difference is called knowledge of music.’ If that makes people mad, or they want to say I’m an elitist, I don’t care. Let’s pull these Duke Ellington scores out. Then we’ll be in a better position to discuss this. A lot of times, they like to get caught up in race, and I’ll say ‘Okay, what about the difference between George Gershwin and Elvis Presley?’ Who’s ready to stand up and tell me that the king of rock ‘n’ roll is on the level of George Gershwin as a musician?

“Anyone who is interested in the evolution of American music has got to reclaim this area, to get our students and the people in our country to think more seriously about what our musical arts represent. It might sound preachy, but that’s not what it is. It’s purely concern for people’s children and the state of the arts in our country. It’s a concern for our culture. A culture is a very important thing. That’s your identity.”

In Marsalis’s wake, a gathering wave of creative young players has taken up the standard and standards of jazz. A case in point is 22-year-old Roy Hargrove who, with three acclaimed albums out and a recording contract to his name, is shaping up as the next generation’s trumpet player. All this delights Marsalis. It shows that the easy-money logic has two edges.

“Why shouldn’t a 20-year-old kid who’s trying to play jazz have a record contract?” he asks, referring to older jazz players who resent the success of younger musicians.

“There’s all kinds of other 20-year-olds who have record contracts who don’t know anything about music. So, I don’t understand why it’s such a big thing for Roy Hargrove to have one. Based on the environment that he’s coming out of, he should have five record contracts. And why shouldn’t he get publicity? Madonna gets publicity. Are we going to submit that she knows more music than Roy Hargrove knows? Do we think that [rap star] Queen Latifah and these people know more music? Now, I’m not saying anything bad about Queen Latifah, but this is the society that we live in. Why should Roy Hargrove be treated differently from any other performer his age?”

As a musician who has lived in the public eye for the last decade and a half, Marsalis knows both the praise and the brickbats and has learned to deal with both. It brings him back to his early days with the Messengers.

“Art Blakey taught me probably the most important lesson,” he recalls. ‘Be courageous. You have to empower yourself. A musician is not a politician.’ He always used to say that. ‘If you are going to deal with this music, you have to come with some honesty and the courage to back what you believe in. Don’t flinch, no matter how painful it gets, no matter what is put on you. You have to accept that and keep going.’ “

On that front, Wynton Marsalis has been the best of students.

by Hank Bordowitz

Source: Arts & Entertainment