Wynton Rebels by Playing It Straight : Marsalis Scores the Garth Fagan Dance Company, Funk-Free

Don’t let the tailored suit and natty tie fool you. Wynton Marsalis sees himself as a rebel. Arriving in town this week for three performances of his “Griot New York” ballet score with the Garth Fagan Dance Company, Marsalis doesn’t understand why he is viewed by many as a jazz traditionalist.

“They talk about me being conservative, man, but the way I see it, I’m the one who’s bucking the trend just by trying to play jazz that swings,” says the outspoken trumpeter and composer, who was once rash enough to criticize Miles Davis’ experiments with funk music. “To me, the ones who are conservative are the ones who are just following the trend of playing all that stuff with a backbeat.”

Marsalis’ score for “Griot New York” (Wednesday at UCLA’s Royce Hall, Thursday and Friday at Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts) underlines his point. Based on music included in his much-praised “Citi Movement” album (as well as selections from several earlier recordings), the work is a sophisticated, multi-timbral composition, teeming with urban rhythms, high-flying improvisations—and very few backbeats.

Echoes of Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, ragtime and traditional New Orleans jazz course through the music, reflecting Marsalis’ desire to compose in a way that embraces the totality of jazz, in all its rich historical complexity.

At its Brooklyn Academy of Music premiere in December, 1991, the music was hailed by the New York Times as “superb in its evocative colors, original in its wit.”

The genesis of the score traces to a poem written by Fagan several years ago. “Garth gave it to me,” recalls Marsalis, “and I went to (writer) Albert Murray’s house and got the poem interpreted. I used that interpretation as an outline to write the music, and Garth began to put the choreography together.

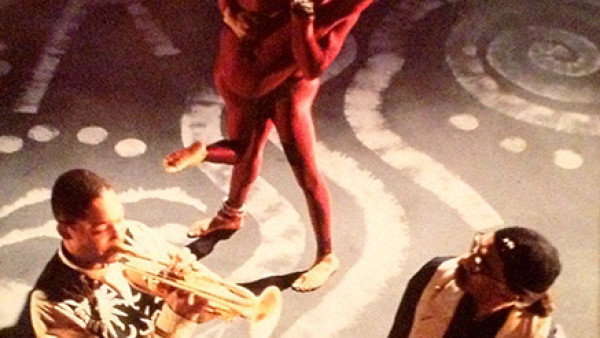

“The ballet is a counterpoint to the music, with the dancers moving on the beats that we play. The musicians’ improvised passages are improvised to what the dancers do, with the dancers’ movements choreographed almost like an orchestration—that’s how Garth does his choreography, like an orchestrated dance ensemble.”

Asked about the balance of improvisation and written music in “Griot New York,” and the extent to which its jazz qualities are shaped by the needs of the dancers, Marsalis reacts with a flash of defensiveness.

“Look, man,” he says. “A lot of the music may be preset, but the swing isn’t preset—and neither are the energy and the motion of the dance.”

Determined to make a point that is clearly important to him, Marsalis continues: “And don’t forget that playing written music is a part of jazz too. There’s a long tradition of people playing parts. But, for some reason, some people think jazz should be reduced to just soloing, or just getting off.

“I mean, just take a look at Michael Jordan. You know that he’s truly a great solo athlete. But, as his career went on, he didn’t just do all those spectacular dunks that he did in the beginning, and his team began to win more. His game became purer, because he started to deal with footwork and more of the subtleties of the game—rather than just jumping 15 feet and slamming the ball. So, many would say, ‘Well, his game changed,’ or ‘It’s less free,’ or whatever. But I think his game became even better. He knew when to use the things that he could do, but he also understood the primary functions and fundamentals of basketball and how to implement them with more success.

“It’s important to realize the same thing in music too. The key to a musical statement is an ensemble statement—not just getting to play your solo and getting off and doing whatever you want to do.”

Marsalis has been a highly visible jazz musician for so long that it’s almost a shock to realize that he just turned 32 Monday. The eldest of four talented musician brothers (saxophonist Branford, producer-trombonist Delfeayo and drummer Jason), the New Orleans-born Marsalis spent more time playing music other than jazz when he first moved to New York City in the late ‘70s. His large plateful of activities included playing with salsa bands, working in the orchestra for “Sweeney Todd” and performing with the Brooklyn Philharmonia.

A 1980 gig with drummer Art Blakey—“he taught me the meaning of being a professional musician”—established him as one of the most prominent of the newly emerging jazz stars of the decade.

But Marsalis has a somewhat less grandiose recollection of the attention he received at the time.

“There wasn’t hardly anybody else playing jazz then,” he says. “It seemed like there were maybe eight or 10 of us, and everybody else was playing fusion, funk, whatever you want to call it.”

“Whatever you want to call it” has been a bone of contention for a long time. Despite Marsalis’ wide-ranging endeavors—from ballet scores for Fagan and New York City Ballet to his appointment as artistic director for jazz at Lincoln Center—Marsalis has a singular view of jazz and his role in the music.

“I’m just trying to swing,” he says. “My whole life I’ve been doing the same thing. I write music, and I pull my horn out and try to play the best way I can play, whether it’s for an audience or for a rehearsal.

“And I play jazz. Which seems to bother some people, because the way I see it, most of what’s celebrated today is done so only if it doesn’t sound like jazz. Most of the things that would be considered innovative by the jazz critical community is not jazz. Like rap music, or fusion. And that’s not to say it’s not good. It’s just to say that it’s not jazz.”

And, if he sounds conservative, Marsalis is willing to accept the label. But the making of labels, definitions, descriptions and interviews are all secondary to the making of music—tolerated because they are necessary parts of a prominent life in the entertainment world. His real work, his real passion, however, lies within the process—within the making of works like “Griot New York,” the appearances with his ensemble, and his endless quest to play music that “swings.”

“I give thanks every time I pick my horn up,” Marsalis says. “This is not something that you can take for granted, you know. Here it is, 1993, and people are still out there trying to swing. Now, that was unpredictable 10 or 15 years ago. But, as long as the Lord lets me stay out here, I’ll keep on trying to swing. Even if there’s only 10 people listening.”

by Don Heckman

Source: Los Angeles Times