A change of key - His Septet behind him, Marsalis takes a new direction

It was one of the most sublime jazz bands of the late ’80s and early “90s, an ensemble so distinctive in personality, so lustrous in tone and so brilliant in technique as to set a standard toward which other young groups aspired. But the Wynton Marsalis Septet, which produced an important catalog of recordings on Columbia, was disbanded late last year, a move that caught many jazz fans by surprise.

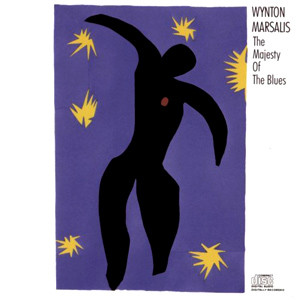

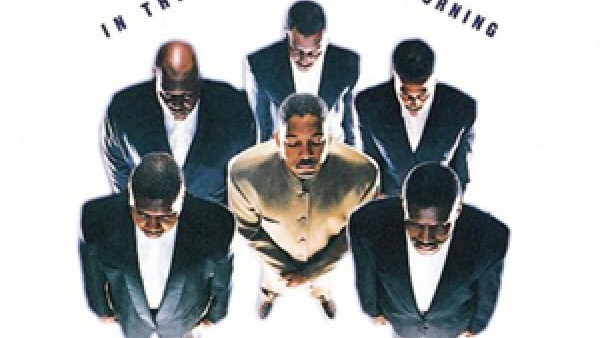

No longer would audiences hear the vibrant, blended reeds of alto saxophonist Wessell Anderson and tenor/soprano saxophonist Todd Williams, the hypnotic backbeats of drumer Herlin Riley and bassist Reginald Veal, the gleaming brass lines of trumpeter Marsalis and trombonist Wycliffe Gordon. With either the up-and-coming Eric Reed or the formidable Marcus Roberts on piano (depending on the recording), the Wynton Marsalis Septet proved that a band of young musicians could create a sound as meticulously polished and cohesive as the finest classical ensemble, without sacrificing the freewheeling spirit of jazz improvisation. So why would Marsalis fold a band he had worked so hard to create and nurture, a band for which he had written his most important compositions, from the incantatory Majesty of the Blues (1989) to the epic In This House, On This Morning (1994)?

“Because it was time for us to go in another direction,” says Marsalis, who brings a new, smaller band to Christ Universal Temple, 11901 S. Ashland Ave., at 7 p.m. April 18, for a concert celebrating the 40th anniversary of jazz station WBEE (1570 AM).

The cats were real tired. Herlin Riley wanted to spend more time with his family, and Reginald Veal had left. And once the bass and the drums change, that’s it, pretty much, that’s the identity of the band.” Indeed, as Marsalis notes in his recent book, Sweet Swing Blues on the Road (Norton), “The bass is the band’s heartbeat. You need a blue-collar worker, dependable, steady, and relentless, to play it. Reginald Veal is such a man. He understands the poetic qualities of his instrument, knows how to make the bass voice resonate in different situations, has a great pulse, loves to groove, and plays with intelligence.”

Of Riley, Marsalis writes, “Herlin is a member of a New Orleans musical family, the : pasties, and grew up listening to his grandfather “tap out various deeply rooted and soulful Crescent City grooves on tables, with spoons, or on body. Drumming is in his genes.”

Adds Marsalis, during a recent dinner conversation in a downtown Chicago hotel, “Without those two musicians, it was just time to do something else, that’s it”

If Marsalis’ words carry a hint of regret over the dissolution of the band, that’s understandable, considering what his Septet meant to him and to the recent course of jazz music. For starters, the Septet coincided with Marsalis’ evolution from the trumpet virtuoso of his earlier, small-group recordings to the major composer he has become. Over the past several years, Marsalis wrote for his Septet works with more dramatic sweep, harmonic originality and bold subject matter than any other young musician in the business.

Just consider the repertoire. “Majesty of the Blues” was not only a reverie on the glories of classic blues forms but also a foreshadowing of the larger, unabashedly philosophical works Marsalis would write for and record with his Septet.

That it contained a movement titled “The Death of Jazz” underscored the boldness of Marsalis’ manner and the political message of his work. In this movement, the composer offered a wickedly dissonant, mocking funeral march for jazz, a music that others had pronounced “dead” but that Marsalis considered perpetually rejuvenating. With his “Soul Gestures in Southern Blue” (1991), Marsalis went even further, positively thumbing his nose at commercial considerations with a vast, three-CD set contemplating the origins and the evolution of black musical culture in the South.

The sultry, steamy atmosphere of the first volume, Thick in the South, the serene spirituality of the second, Uptown Ruler, and the crying blue notes and gently rolling tempos of the finale, Levee Low Moan, suggested a prodigious young man taking stock of his musical and cultural heritage. With each Septet recording thereafter, Marsalis ventured into utterly unexpected directions. Surely the intricate counterpoint and densely chromatic harmonies of Blue Interlude (1992) came as a shock after the warmly atmospheric music of “Soul Gestures.”

The roaring sound and restless rhythms of Citi Movement (1993) marked Marsalis’ deeper excursion into urban themes, in a sophisticated tone poem that Marsalis had written for Garth Fagan’s ballet Griot New York. The high point came with In This House, On This Morning (1994), a radiant two-CD set in which Marsalis’ Septet evoked the form and spirit of a black church service through instrumental hymns, altar calls, benedictions, chants, processionals and recessionals. At once erudite yet accessible, dramatic yet spiritual, the piece ranks with such enduring, 20th Century counterparts as Duke Ellington’s Sacred Concerts and various, extended solos of John Coltrane.

In this crowning piece, and in the works leading up to it, Marsalis disproved the critics who, in the ’80s, had labeled him a mere imitator of earlier artists, such as Louis Armstrong. With “In This House,” “Soul Gestures,” “Blue Interlude,” “Citi Movement” and “Majesty of the Blues” (as well as the ebullient 1990 soundtrack for the film Tune In Tomorrow), Marsalis had conceived compositions so original, and had tailored them so closely to the talents of his Septet, that it is difficult to imagine anyone else playing these works. Indeed, with the demise of his Septet, Marsalis himself seems unlikely to be performing this repertoire. He will have to move on to other music, other projects, other ideas.

“People are saying that the end of the Septet means I’m going on a sabbatical, but it’s not really that at all,” says Marsalis, who for the past four years has served as artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center.

“Basically, I’m just writing music for different kinds of ensembles now. I’m doing a piece for choreographer Twyla Tharp, and I’m writing a string quartet for the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. “I’m also going to work a lot more on directing Jazz at Lincoln Center. A lot of times, I would be doing the Lincoln Center work in between doing everything else, and I wasn’t focusing the type of attention on it that I should.”

Most persistent among Marsalis’ many distractions was the New York jazz press, which attacked him for the allegedly conservative thrust of his programming. Heated exchanges between Marsalis and his critics were documented in the New York’s newspapers.

“That whole thing was very low,” says Marsalis. “There was a misrepresentation of facts, and it left a bad taste in my mouth, personally. “It’s quieted down for now, but it will build back up, it won’t go away, you can be sure of that. “My feeling is that I’m not going to engage in that anymore. I answered that first round, but the second round I’m not going to say anything about.

“I’m not going to be in a position where every time I make a decision and try to do my job, I have to answer to some body of people. That’s unfair. Nobody else [at Lincoln Center] has to do that”.

Certainly Marsalis has plenty of other work to do. Beyond his recent book, a deliberate attempt to demystify the life of the jazz musician, Marsalis will appear in a taped series of young people’s concerts, to be broadcast this summer on PBS (as well as the BBC in Europe and Japanese television). And though his Septet is disbanded, some of its recordings are still in the pipeline. Yet to come is a CD boxed set featuring the Septet’s live performances at the Village Vanguard, in New York. Still more important is “Blood on the Fields,” a vast, three-hour work that Marsalis premiered last year at Lincoln Center, subsequently rewrote and recorded earlier this year with the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, plus singers Jon Hendricks and Cassandra Wilson. “We’re extremely excited about that project,” says George Butler, jazz chief at Sony/Columbia.

“Wynton has been working on that a long time, and it means a lot to him.” Adds Marcus Roberts, a longtime Marsalis confidant, I’d say ‘Blood on the Fields’ is probably the best thing Wynton has done, including ‘In This House.’ People will be amazed.”

And just last week, Marsalis released Joe Cool’s Blues, with his Septet playing a newly recorded version of Wynton’s score for a 1987 Peanuts television special “This Is America Charlie Brown: The Wright Brothers at Kitty Hawk.”

Though movements titled “Snoopy & Woodstock” and “Why, Charlie Brown” may suggest lightweight material, the music is anything but. These pieces, and others, overflow with the Southern sensibility, blues vernacular and meticulous voicings that have been hallmarks of the Marsalis Septet over the years. (The recording also includes music of Vince Guaraldi, performed by the trio of pianist Ellis Marsalis, Wynton’s father.)

As both the Peanuts score and the forthcoming young people’s concerts suggest, Marsalis plans, as ever, to direct a good deal of his time toward kids. “There are a lot of fine young musicians coming up, pianists, bassists, trumpeters, everything,” says Marsalis, who will lead a free Arts and Music Seminar for high school students at 2 p.m. April 18 at the aforementioned Christ Universal Temple.

“Believe me, the kids want to swing,” adds Marsalis, 33. “They want to play jazz because it’s fun. They just need to know how. It’s our job to teach them.”

By Howard Reich

Source: Chicago Tribune