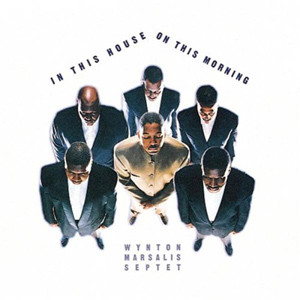

In This House, On This Morning

The audience caught fire when the Wynton Marsalis Septet premiered this full scale suite, at a gala concert in Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall on May 27, 1992. Wynton structured the composition to follow the form of many African-American church services, which have twelve parts, just like the blues. It charts a journey of hope, failing, and redemption, from a Sunday sunrise “Devotional” and “Call to Prayer” to “Pot Blessed Dinner,” the always delicious home cooked meal immediately following the service. Give it a listen, and you’ll likely agree with the opening night audience, that Wynton took that preacher’s advice to heart – “Start low, go slow; reach a little higher, catch on fire!”

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Septet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | March 22nd, 1994 |

| Recording Date | May 28-29, 1992; March 20-21, 1993 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | C2K 53220 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| CD 1 | ||

| Devotional | 3:31 | Play |

| Call To Prayer | 5:58 | Play |

| Processional | 4:35 | Play |

| Representative Offerings | 6:46 | Play |

| The Lord’s Prayer | 3:47 | Play |

| Hymn | 3:56 | Play |

| Scripture | 4:01 | Play |

| Introduction to Prayer | 2:23 | Play |

| In This House | 3:52 | Play |

| Choral Response | 4:27 | Play |

| Local Announcements | 3:33 | Play |

| Altar Call | 1:29 | Play |

| Altar Call (introspection) | 8:41 | Play |

| CD 2 | ||

| In The Sweet Embrace Of Life Sermon (excerpt) | 16:04 | Play |

| Son | 4:58 | Play |

| Holy Ghost | 6:56 | Play |

| Invitation | 5:59 | Play |

| Recessional | 10:33 | Play |

| Benediction | 3:25 | Play |

| Uptempo Posthude | 7:44 | Play |

| Pot Blessed Dinner | 2:39 | Play |

Liner Notes

PRAYER

(as sung by Marion Williams)

TO THEE, O LORD, We say Yes, THIS DAY

And in this house, Yes swells in our SOULS

To Praise Thy vast creation,

And ring the bells whose melody

Affirms.

Oh! Yes!

Bells which sing of sweet love,

Rebellion lost.

And though ten-thousand suns-rise,

Those bells yet ring still ring true.

Love.

IN THE SWEET EMBRACE OF LIFE

1. The liturgical pearls of our culture originated with the chattels who loved percussion and never failed to remember the eternal drum beats of human affirmation. Often expressing their needs in secret, with the moon for a steeple, they softly sang music that had possession over a lofty and grand melancholy. Socially motherless children, unclaimed by the protective wing of the law, spiritual eagles who could be treated like flies, they also crooned because, in the sweet embrace of life, their souls were happy. That heroic, transcendent joy caused the less advanced to mistake them for naïve creatures. Even so, after bondage they developed their ceremonial flair for musical depth. In so many houses, on so many Sunday mornings, their souls taught all who heard that the freedoms of the heart come of compassion and gratitude, gratitude felt even while seeking light during the long darkness of injustice. The stomping of their feet against the dirt of the earth’s drumskin or against the wooden drumskin of the church floor, their clapping in the alto, tenor, and bass registers of their palms, and the lucid intensity of their exaltations brought the flesh and the spirit together in an understanding that the heroic soul is the only solution to the decadent orchestration eternally wrought by folly, corruption, and mediocrity.

That liturgical drama of song and percussion, of eloquence and incantation, of the sun and the moon rising in absolute light and fullness from the bottom of the social valley, added an unsentimental spirituality to this culture, a fresh language for the dialogue between the all-too-human and the divining, enlivening spark of the invisible. So whenever we feel that old and noble closeness to the soul of all meaning, we are again returned to the essence of the spiritual autobiography that was first enunciated in song of grand and lofty melancholy, in song accompanied by the percussion that had custody over the indivisible rhythms of existence. We feel the warmth and the calm, the compassion and the integrity, the sense of tragedy as well as the will to transcendence that is the moral essence of courage. In all, we know the illumination that is the sweet embrace of life.

2. On May 27, 1992, Wynton Marsalis premiered this long, immoderately soulful, and often astonishing work in Avery Fisher Hall at Manhattan’s Lincoln Center. There had been a graduation ceremony held in the hall earlier and the concert began at 9:00 instead of 8:00, the first notes coming out of the musicians’ instruments near 9:30, due to the usual seating delays and an introduction by Ed Bradley, in which he referred to Marsalis as the most important figure in American music. Some surely bristled at that, either out of jealousy or resentment of the fact that Marsalis has become a success on terms of his own and continues to develop what is perhaps the richest single musical talent of the last half-century.

Without precedent, Marsalis has gone on to conquer two quite different musical traditions, performing European concert music with a freshness and audacity that matches his achievements in jazz, which are, however, much larger. As a performer of concert trumpet pieces, he is one of the two or three best in the world. In jazz, Marsalis has proven himself not only the greatest trumpet play of the last thirty years but also the greatest bandleader since the peaks achieved by the Modern Jazz Quartet, Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Horace Silver, Charles Mingus, Ahmed Jamal, and John Coltrane. He now adds to those marvels the fact that his is perhaps the most imposing compositional talent in contemporary American music, regardless of idiom.

The breadth of those gifts was stated so overtly in the premiere of IN THIS HOUSE, ON THIS MORNING that there was a special sense of community felt within the standing ovation which followed the last notes. The two-hour work had given the audience a panorama of human feeling rising through a form shaped in emulation of an Afro-American church service. One knew that evening in that hall that the talents of Wes Anderson, Todd Williams, Wycliffe Gordon, Eric Reed, Reginald Veal, and Herlin Riley provided Marsalis with one of the greatest ensembles in the History of jazz. Those musicians had also set the tone for the piece before the first note was written. Says Marsalis:

Almost everyone in the band grew up playing church music and what truly spurred my desire to write this music was the many hymns and shouts that they sing on the bus as we travel, at sound checks before concerts, and after meals. With the demise of a viable blues tradition in popular music, most of the younger jazz musicians learn the expression necessary to play music either in church or from someone close to them who happens to be a musician. In the band, everyone, with the exception of Todd Williams, comes from a musical family, and all of the guys, with the exception of Wes and me, grew up playing in church. Reed’s father is a preacher and you can hear the reality of that in his playing. Listening to all of them made me want to put that feeling in a long piece and reassert out here the power that underlies jazz by constructing a composition based on the communal complexity of its spiritual sources.

The piece demanded everything of its players-passion, virtuoso technique, top-of-the-line reading skills, and the sense of extended form in which each improviser develops the essences of the theme and the particulars of the preceding player’s spontaneous variations. Though the structural accomplishments were as numerous as they were formidable, Marsalis and his men executed a victory far beyond the technical. They arrived at that place where the wick of the soul caught fire, casting a large and variously shaped light through the wonderfully designed lamp that was IN THIS HOUSE, ON THIS MORNING. That fiery wick spoke its brightness through the bush of silence and darkness with such aesthetic authority that Pearl Fountain, Marsalis’ housekeeper and a veteran of many, many long mornings and evenings in church, said of the performance, “God visited you all last evening.”

The band went into the studio the next day and the results are here.

3. The arrival of this work might surprise those who have developed a toughness adequate to face the many disappointments of this era, a period in which the decadent and the inept are celebrated as though the loss of purity into darkness is an achievement. With pop music being played in Afro-American churches, distinguished only by religious lyrics, we know that things are in bad shape, that the flame of the tradition which gave our modern age an original, subtle, and incinerating heat has come to sputter even in the temples where the soul is a central subject.

Because IN THIS HOUSE, ON THIS MORNING so thoroughly expresses the meanings behind the ceremonial imperatives of Afro-American rhythm and tune, the soul is given its due. What we hear is a work that steps right up next to Duke Ellington’s “Black, Brown, And Beige” in its command of material. Ellington was always at war with the minstrel limitations of popular Afro-American imagery, seeking to express the range of the Negro spirit that had so influenced the richest aspects of our national identity and that had given so much to the modern vocabulary that expresses the life of our technological era, an epoch in which our machinery is a set of Corsican twins, one good, one evil, forever at war. In this period of overweening decadence, when the opportunistic cesspool of vulgarity is either misconstrued or deceptively celebrated as a fountain of vitality, Marsalis is the point rider in a renaissance of younger jazz artists who would reverse the fall of our aspirations by returning a revolutionary high-mindedness to our ongoing democratic discussion of life’s meaning. He seeks to reiterate in his own terms the very elements that gave our American culture such grand vitality in its better years.

This work is part of that vision. Marsalis recognizes the artistic and structural possibilities of the Afro-American church ritual, just as the masters of the European Renaissance saw so well what could happen when they brought the complex human insights of the Biblical tales together with the mastery of perspective. IN THIS HOUSE brings the broad spiritual perspective at the root of jazz together with the intellectual achievements that have taken place in an art built upon the melody, the harmony, and the rhythms of the blues. Marsalis is capable of this because he knows a truth quite profound: the blues is the sound of spiritual investigation in a secular frame, and through its very lyricism, the blues achieves its spiritual penetration.

4. I wanted to express the full range of humanity that arises in a church service, from deep introspection to rapture to extroverted celebration. The form, supplied by Reverend Jeremiah Wright, is a typical Afro-American church service. It just so happens that the form that he told me had twelve sections, like the measures in one chorus of blues. I found that the break following every four sections gave the piece three movements. Within this form, I also drew on my own connection with many types of church music and music of various sorts. So IN THIS HOUSE has a wide range of things, beginning with “Devotional” and ending with that country feeling of community when the food comes out after all the aspects of the ceremonial have been completed. The last part, which is sort of an emotional and cultural coda, is called “Pot Blessed Dinner.”

Overall, what I wanted was to give musical structure in my personality to the communal elements that transcend any single place. Even though the form is definitely American, I wanted to open the interpretation up to all kinds of musical approaches. That’s why the piece has the emotion of traveling and visiting many different kinds of churches and many different kinds of services, from the highly refined all the way to the backwoods, way down in the country. IN THIS HOUSE moves from the feeling of the black American church to the study of Bach chorales, even the feeling of ritual in ancient religious forms and the sounds one hears when in Middle Eastern countries. By using the blues as a fundamental element, I was also able to ground the music in our culture while stretching it onto an international plane. But that’s natural to jazz because it builds upon the blues and upon swing. The percussive sensibility of the blues comes from African-based music, and the melodic and textural characteristics can be found in folk and spiritual musics all over the world.

The blues is central to what I’m doing with the structure here. The basic harmonic progression of the blues comes from the “amen cadence,” I, IV, I, which we have all heard used so many times in and out of church music to conclude a piece. So it’s basic to our hearing. Now the blues is I, IV, V, IV, I. If you don’t have the V chord you can still have a blues, but without the IV chord, no blues. So my intention was to reconcile the secular nature of blues expression with the spiritual nature of its sources. It is also another example of my interest in one of the main achievements of jazz, which is fusing the Apollonian and the Dionysian, the intellectual/spiritual and the sensual. The momentum of the piece is based on Albert Murray’s description of swing as “the velocity of celebration.” That means that the sound of praise is in the rhythm, too.

5. A close observer of Marsalis is Marcus Roberts, who worked with him for five years. Recently, Roberts had to perform this composition when Eric Reed, now the regular pianist in Marsalis’ group, was ill. He knows it well and has some very important observations about this grand offering:

What is amazing about this piece is how it gets all the way down into the depth of the church service. This music is about soul, soul as pure as it comes. If it wasn’t, somebody like Marion Williams wouldn’t have anything to do with it. People like her don’t play around. That’s why the first thing I find remarkable about it is that somebody who didn’t grow up attending regular Baptist church services could capture so authentically the feeling of that experience. Right here, in this incredible piece of music, Marsalis gets to the heart of the issue better than most people who participate in it on a weekly basis.

This has a special meaning for me because I remember when Marsalis used to call me and ask me to show him some gospel chords, since he knew that I had grown up in the church. He knew I knew the church, and I do know the church. I know how it feels, I know how it goes. I’ve played in the church Sunday after Sunday. Now he’s developed from those phone calls all the way to what we hear in that third movement, where everything he has set up on the first two movements comes together. The architecture is total on every level. There’s nothing missing. That’s why it captures so perfectly a church service, which is always an attempt to bring the entire meaning of life into structure, an attempt to face our shortcomings, be thankful for our blessings, and recognize the wonders of the works of God. Marsalis didn’t miss a thing. He got it just right.

But what he did that will stand forever in musical terms is that he brought off the key to what I would call true innovation, which is when you find basic solutions to basic problems through profound achievements. In that respect, this piece represents a step forward and backward at the same time. It’s totally modern and totally basic. The harmonic sophistication is just as profound as the grooves. Think about that. So are the melodies, the orchestrations, all of it-extremely sophisticated and basic. Whatever you want, wherever your musical taste comes from, there’s something in there for you. So the achievement is that it moves us along with all the complexities of our own times while it also recaptures the early essentials laid down by masters like Jelly Roll Morton, who always got the very most out of his bands, compositionally and improvisationally. That’s why it towers above anything I’ve heard written since the death of Duke Ellington. Nobody writing music today could have done this except Marsalis. IN THIS HOUSE, ON THIS MORNING brings a lot of knowledge together and it also gives us another insight into how jazz form and structure are being rediscovered.

Now you know how things go in this era. It may take a while for some people to get with this piece. But when they do get to it, they will discover that this piece represents the finest use of a band with this extreme level of talent. He wrote very brilliantly for all the men in that group, and they preformed it very brilliantly. You can play it after Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, Jelly Roll, Miles Davis with Coltrane and Cannonball, Coltrane with his own band, Monk-whatever you want to play-and there’ll be no drop in quality. In fact, the extended achievement is unequaled for a small jazz band by anybody. Two hours of music this tight, this well organized? No one’s ever come close to that.

You see, Marsalis was sent here on a mission and that mission is made much clearer in this particular composition. Not only is there an incredible development of the harmony from the first section to the last, but Marsalis has this phenomenal understanding of how to put rhythm with melody and with harmony so that the grooves have thematic relationships as well. That’s extremely rare. It allows him to develop different things in isolation, in fragments, in counterpoint, in different registers and rhythms of the band at the same time. No doubt about it: This is music that is deeply felt, well thought out and right to the point for the entire two hours.

Like I said, only Marsalis could have done this. If somebody else could have done it, we would have already heard it done. This is a masterpiece, which is how blessings make themselves manifest in art. Yes: Marsalis took the whole idea of jazz composition a long ways forward with this one. True lovers of music and true students of music will understand what I’m talking about immediately; the rest will catch up sooner than we might think. Something this great can only be denied for so long.

6. It is Sunday morning. The regular believers and the visitors are gathered. They have come for the particular purpose of feeling affirmation, which is the force that touches them with the value of existence and is the sword that raises itself against denigration. There are the old who have heard and observed the power of the Word for many years. There are those younger who have come into adulthood learning the strength that results from faith and the will that it allows. There are children, some shy and quiet, others barely restraining their boisterous inclinations, still others who wonder if they someday will be in the choir or become deacons or stand before the congregation passing forward the Word of light that will dispel the doubting darkness.

The first movement opens with “Devotional.” Led by one deacon and followed by whomever is present, this is the informal praying and testifying to God that takes place before the beginning of the formal service. In the masterfully voiced abstractions of this prelude, we hear the main themes and harmonies that will be developed throughout the work. The band superbly executes all the elements-the keening, the deep voices, the tambourine rhythms, the chords, the ringing church bells that will recur throughout, sometimes on the piano, sometimes on the bells of the cymbals, sometimes in the bass, sometimes from the horns.

Next comes the beginning of the service, “Call To Prayer,” a bold appropriation of the Middle Eastern sound of the Holy Land, that speaks across the ocean to blues and swing, creating a conversation between the duple and triple meters upon which the rhythms of the work will develop over its entirety. In the hot dialogue with the perpetually marvelous Todd Williams, Marsalis once more proves himself the king of avant-garde jazz trumpet with a remarkably audacious performance that no one else could bring off, or has ever approached. Formally, the trumpet exchanges extend by one bar, the tenor by two, the trumpet on one chord, the saxophone harmony extending downward, its progression the same as that which the bass will play in the last section of this movement. The notes of this bass progression are also used in the third movement, forming the melody “In The Sweet Embrace Of Life” as well as the chords. The two-part interlude that precedes the final trumpet statement foreshadows “Representative Offerings” in the horn writing and “Hymn”/”Scripture” in the brief piano waltz. The transitional material for trombone-delivered over a ringing bell-perfectly fuses the oppositional aspects of the trumpet-saxophone exchanges into a single line as we shift to the next part.

“Processional” depicts the choir, the deacons, and the minister coming down the aisles and taking their places at the front of the church. This is always a moment of jubilation, with the robes flowing and the sound of a mighty song beginning in the back of the church, choir members smacking tambourines as they walk, the deacons and the minister turning and smiling at the congregation. This part presents material that will be given variation in the second movement’s “Hymn,” “Scripture,” “Prayer Response,” and “Altar Call.” The improvisations by all of the horns have superior swing, clearly supported and inspired by the high style rhythmic command of the extraordinary rhythm section.

“Representative Offerings” are the petitions from the minister to God. This is where the minister’s voice first comes forward, asking for grace, for support, for strength. This section is influenced by Ellington’s Afro-Bossa and The New Orleans Suite. Marsalis had in mind:

Something exotic, something out of the ordinary, something that carries you into the other world that the minister is addressing. It’s also about the fact that whenever people offer other people something in the Bible, it’s always exotic. Like Duke pointed out-apes and peacocks were what the Queen of Sheba brought to Solomon.

Wes Anderson’s feature begins as a response to a drum rhythm, then inhabits the entire environment of the piece with the level of soul, thematic invention and control, harmonic bite, and rhythmic fluidity possessed by only the great reed players. The same must be said of Todd Williams, whose two features – one on clarinet, one on tenor – emanate from an equally radiant foundation of talent.

Purity is the essence of this movement’s last part, “The Lord’s Prayer,” a variation on the sound of a Gregorian chant, broken up into octaves and done in the chorale style of Bach with blues harmonies. For all of that, it extends upon material from “Devotional” quite clearly at the same time that the elemental “Altar Call” is foreshadowed within all of this sophistication. It is also significant that the notes of the bass progression again form the melody to which the words “In The Sweet Embrace Of Life” are sung during the main sermon in the third movement. Here Marsalis’ harmonic originality comes forward with its full weight, sounding unlike Ellington or anybody else. At the conclusion, the alto saxophone line refers back to the movement’s opening statement of the sopranino saxophone, while bells are rung on the piano and the bass.

The second movement opens with “Hymn,” “an allusion to the kind of hymn you might hear sung in somebody’s house. Its form is ABCCBA, with the breaks allowing me to ring bells on the piano.” Eric Reed is the central improvisor, performing with the lilting optimism and determined swing he calls upon throughout the piece. “Scripture” is self-descriptive. It features the lyrical eminence of Wes Anderson and refers back to the hymn. This sections ends on a reverse “amen cadence.”

“Prayer” is in three sections. The trumpet gives the “Introduction To Prayer,” Marion Williams sings the prayer (“In This House”), then there is a “Choral Response” separated by a short piano and bass interlude. For his part, Marsalis reaches a rare level of melodic majesty, stretching his horn into the area of elevated sound we associate with the humbling authority of Mahalia Jackson. Williams then sings with the spiritual breadth that creates a line from the human heart all the way to the explanatory star at the center of creation. Bells ring, forming an interlude leading to “Choral Response” which is comprised of material that comes from “Devotional,” “Call To Prayer,” “Representative Offerings,” “Scripture.” After a trumpet feature of peerless rhythmic complexity, there is a brief section for trombone and alto in which the saxophone foreshadows “Altar Call.”

“Local Announcements” take place when the congregation is told of forthcoming picnics, fund raisings, births, the arrivals of messages from vacationing members, exceptional performances by students in schools, the winning of scholarships to college, and so on. Marsalis says:

It starts off like a four-part barbershop quartet, representing a country, down home church. Then individuals take solos that represent announcements. After that, the bass sets the ambience with the slapping technique and they all come together in a part that celebrates how religion brings people together, recognizing their individual souls and their relationships to others.

“Altar Call.” This is where you call everybody to pray for specific members of the congregation. Some go forward to the altar for the prayer, then return to their seats. This has two sections. In the first, each horn comes in one at a time. Once each of the horns is in, we go back through each measure the opposite way, which is like people going up to the altar and returning to their seats. Here I’m using a pentatonic bass. Next, I want the feeling that comes when the members of the congregation are deep into the religious emotion and are responding to each other with great fervor. During these two choruses, which are blues, we also hear a drum solo. After the statement of the line, Todd Williams is featured. This movement ends with fragments from the entire piece, giving us a cross section of feeling and musical elements.

Those two choruses of blues writing, almost eerie in their command of the molten Negro religious voice – the ghostly moans, the humming, the chanting – reach as far down into the soul of the matter as anything coming from this cultural source. We hear what Anthony Heilbrut was referring to when he wrote in a New York Times review of a 1992 book about Thomas A. Dorsey: “Moans, with their relentless blue tonality, provide the basis of black song: spirituals, gospel, blues, and jazz.”

The third movement is a staggering culmination. Now the preacher is at the pulpit, his robes rustling like the wings of justice, his voice winding up with the spirit as he gets to his rhythm, that rhythm finding a confident lope that makes the text of his message smolder into the light of a low fire. Slowly, with its measured confidence spiking up into higher and higher flame, the incantational message starts to billow and shoot its percussive cracklings and explosions into the air, the air now a horse galloping downward, its flanks jerking under the spurs of light made fiery by the divine jockey of revelation, that mighty jockey leaping its mount overall the obstacles to recognition as the mysterious makes itself first audible then visible, descending at a swifter and swifter clip, soon lowering the thunderous pulsation of its power into human flesh, moving through the hair, the sweat, and the twitches until it arrives in the infinite valley of the heart; then that man or that woman, now in the aisle, now moving like one of the brass circles shaking on a tambourine, is lifted higher and higher and higher by the aggressive structure of connection that is the immortal light of the soul called into the hot, calming, and perpetual arms of the Holy Ghost.

The sustained quality of the writing and the playing gives this movement classic immediacy, the feeling that something new is achieving such feats right before us that it will be toasted and remembered until the end of the world. Reginald Veal’s startling bass solo is the beginning of the sermon, the preacher clearing his throat and selecting the elements that will lead us into the theme. Veal seems to appropriate the kind of playing heard from Son House on “Pearline,” which is to say that he sidesteps the flamenco cliches that can strum a listener into a coma. When the piano comes in, with the same progression from “Call To Prayer” and “The Lord’s Prayer” of the first movement, we hear the main theme of the main sermon, “In The Sweet Embrace Of Life.”

The form comes from something I was told when I asked a reverend known for preaching hot, fiery, country sermons what his philosophy was. He said, “It’s very simple. Start off low; go slow; get higher; catch on fire.” So this part is structured on that conception, a sermon in three sections, which I call the “Father,” the “Son,” and the “Holy Ghost.” Each section is a little faster and higher than the one before, going up a half step, from A to B-flat to B natural. In the fast section, where the Holy Ghost arrives, the piece goes up yet another half step to C for the trumpet solo.

Player after player improvises or executes parts with an introspective-to-spirited authority that holds boredom at bay, surprising with some unexpected expression of quality at every bar; Veal, Riley and Reed swinging and grooving their way into the upper echelons of the pantheon; all of it reaching the peak of the sermon with a hat-muted trumpet feature, an inflamed rhythm section, and shouting horns that project an intensity unusual even for jazz.

Next we have “Invitation” where new members are brought into the church. This features Wes Anderson in one of the great contemporary improvisations, a sensation of nuance, formal command, and emotional complexity. His work is followed by a glorious ringing of bells, an interlude for the thematic rhythms of Herlin Riley’s tambourine, more bell ringing, then a feature for the singing keyboard of Eric Reed. This section builds through horn improvisations to an elevating counterpoint that slides into the chant of the next section.

“Recessional” captures the choir and the deacons coming back down the center aisle, the ceremonial reverse of “Processional.” It is a 7/4 chant, with hand clapping, a fusion of the duple and triple meters that have served thematic roles throughout the work. Todd Williams is the luminous tenor voice. “Recessional” melts into bell-ringing by the horns. The concluding melodic statement from the pulpit, “Benediction,” is delivered first by Todd Williams. A brief ringing of bells leads to the theme in harmony, eventually giving way to the bass playing the line while the horns ring bells.

“Uptempo Posthude” takes us out into the afternoon with the congregation, first milling and speaking in the aisles, amening and making observations about the message, celebrating the good feeling that comes when one witnesses the widening light of the truth. Now, with a long sermon done, the visitation of the spirit clear to all, the wonders of the universe still ringing in mind through the metaphors just witnessed – song, speech, human animation – those regular members, those newly declared members, the old, the young, and the in-between, leave satisfied, for they have experienced, in miraculous variety, “In The Sweet Embrace Of Life.” The only thing left to do is go somewhere comfortable, put feet under the table and satiate the appetite for down-home cooking, “Pot Blessed Dinner.”

– Stanley Crouch

Credits

Performed by the Wynton Marsalis Septet:

Wynton Marsalis – trumpet

Wycliffe Gordon – trombone

Wessell Anderson – alto saxophone

Todd Williams – tenor and soprano saxophones

Eric Reed – piano

Reginald Veal – bass

Herlin Riley – drums

with special guest: Marion Williams – vocals

Marion Williams appears courtesy of Shanachie/Spirit Feel Records

Music Copyist: Ron Carbo

Produced by Steve Epstein

Executive Producer: Dr. George Butler

Mixing and recording engineer: Mark Wilder

Assistant BMG Engineer: Sandy Palmer

Recorded May 28-29, 1992 and March 20-21, 1993

Recorded digitally into the SONY PCM 3348 Tape Recorder at BMG Studio A, NYC

Mixed at SONY Music Studio B, NYC into the SONY K1183/84 20-bit trasport/converter

Mastered using SONY 20-bit SBM Technology for high-definition sound

Piano provide by Steinway

Management: The Management Ark, Inc. Santa Fe, New Mexico

Edward C. Arrendell II, President

Art Dirction: Josephine DiDonato

Design: Aimée Macauley

Photographer: Michael Llewellyn

Special thanks to Reverend Dr. Jeremiah A. Wright, Jr., Trinity Church of Christ, and special assistants Earl Johnson, Ron Smith, Rumas Barrett, Debra Parkinson and Dann Wojnar

All songs composed by Wynton Marsalis

Published by Skaynes Music (ASCAP)

“Prayer” lyric ©1993 Skaynes Music (ASCAP) All rights reserved, used by permission.

In this House, On This Morning was commissioned by Jazz at Lincoln Center, Lincoln Center Inc. and premiered May 27, 1992

Personnel

- Wess “Warmdaddy” Anderson – alto sax, sopranino sax

- Eric Reed – piano

- Reginald Veal – bass

- Wycliffe Gordon – trombone

- Todd Williams – tenor sax, soprano sax

- Herlin Riley – drums, tambourine

- Marion Williams – vocals

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Altar Call (rehearsal) - Wynton Marsalis Septet at Jazz in Marciac 2008

-

Videos

Videos

Son (rehearsal) - Wynton Marsalis Septet at Jazz in Marciac 2008

-

Videos

Videos

Wynton on “In This House, On This Morning”- CBS The Early Show

-

Videos

Videos

Wynton honored with the Algur H. Meadows Award 1997

-

Videos

Videos

Choral Response, Local Announcement - Wynton Marsalis Septet at Vitoria Jazz Festival 1994

-

Videos

Videos

Introduction to Prayer - Wynton Marsalis Septet at Vitoria Jazz Festival 1994

-

Videos

Videos

Wynton Marsalis Septet at The Royal Albert Hall (1993)

-

Videos

Videos

Holy Ghost - Wynton Marsalis Septet at North Sea Jazz Festival 1993