Wynton Marsalis Imagines Buddy Bolden’s Jazz On-Screen: ‘He Was Bringing Fire’

As much as jazz could possibly have an inventor, that person would be Charles “Buddy” Bolden. But although he is celebrated as a seminal figure in jazz at the turn of the 20th century, very little is actually known about the African-American cornetist and composer’s life. There are no existing recordings of Bolden, who spent more than 20 years in an asylum before his death in 1931.

So, how do you write music for a musician you’ve never heard? You enlist Wynton Marsalis, one of jazz’s most decorated composers and performers. Marsalis’ proven track record made him the right man for the job of creating and playing the music for Bolden: Where The Music Began, the jazz biopic in theaters May 3 about the New Orleans cornet player.

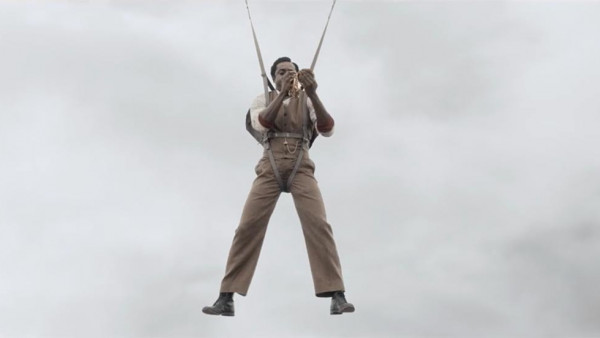

Much of the plot of the film comes from urban legends surrounding Bolden. It was the task of Marsalis to create music that would live up to these stories. One scene early in the film is set at a picnic. Buddy and his manager soar high above a public park in a hot air balloon and, at his manager’s urging, Buddy jumps and plummets out of the balloon toward the picnickers. But as soon as his parachute opens, Bolden lifts his cornet to his lips and blows, drawing attention away from the ensemble playing on the bandstand.

“It didn’t happen in real life, but I’m sure it’s something that a manager would suggest,” Marsalis says. “However, the dynamics at a picnic are accurate. It was John Robichaux’s orchestra. He was a bandleader at that time and a rival of Buddy Bolden’s.”

Before Bolden dropped in, Robichaux’s orchestra had been playing American standards. “They played with a great deal of feeling. It’s just they did not improvise and Buddy Bolden represents the kind of wild, free spirit in which he did represent an entire new way of playing music,” Marsalis notes.

Bolden and his band overtake Robichaux’s orchestra, and put on an invigorating show, employing the call-and-response elements now well-known in jazz. Marsalis made sure to have the two competing songs in this scene speak to each other.

“I have respect for Robichaux’s way of playing,” he says. “I just think that the improvisation was too much. It was such a new thing and Buddy Bolden himself was such a magnetic personality and genius as a musician that when you heard his sound it was overwhelming. It was so danceable and infectious that Robichaux, his style couldn’t compete with Buddy’s style.”

It was Bolden’s improvisation and outrageous sense of showmanship that set Bolden apart from any other musician at the time. “Buddy Bolden was like Prometheus,” Marsalis says. “He was bringing fire! And he also synthesized the styles that existed at that time. He could play sweet on a waltz. He could play pretty melodies, but he could also holler and shout like a sister in church.”

In order to imagine this signature sound, Marsalis says he first had to make some assumptions about how good Bolden was — “He was called King Bolden” — and secondly, he had to make a composite sound based on three horn players who were influenced by Bolden and were recorded in their own lifetimes. Those three successors were Freddie Keppard, who played in a ragtime style, Bunk Johnson, who played with a smokey sound and a very straight lead, and King Oliver, who Marsalis says played with dignity “but also create a lot of vocal sounds.”

“I put those three styles together and I figured, ‘OK, these three musicians were all influenced by Buddy Bolden, so they took an aspect of Bolden’s personality to construct their playing. So, Bolden could play better than all three of them,’” Marsalis says.

When it came to playing like Bolden, Marsalis says he would try to embody how he imagined Bolden played: Energetic, authoritative and definitive. Marsalis would often hold a note to the end of his breath and play strong leads. “I tried to just take the kind of extremes I feel that he probably played with.”

In the film, Bolden enjoyed a meteoric rise and at one point, was performing every night. Marsalis notes that fans often said Bolden played as if his heart was breaking. “He was the type of musician whose sound had the depth of human feeling that touched listeners and they didn’t forget that sound. That sound put a healing on them,” Marsalis says.

Bolden arrives in theaters on Friday. Marsalis spoke with NPR’s Audie Cornish about the obstacles Bolden had to overcome in jazz and in life and why his legacy is not more widely known. Hear their conversation at the audio link.

Source: NPR

———————————————————-

AUDIE CORNISH, HOST:

How do you write music for a musician whose work you’ve never heard, whose work no one has ever heard because there are no recordings? On the case of Buddy Bolden, a founding father of jazz, it helps that one of the greatest performers in modern times grew up in his hometown, studied his work…

WYNTON MARSALIS: Well, I mean, that’s my tradition. It’s my instrument. It’s what I love.

CORNISH: …And of course can carry a tune.

MARSALIS: Little things like (vocalizing).

CORNISH: Wynton Marsalis, one of the most decorated composers and performers in jazz, took up this task for the movie “Bolden.” Bolden a cornetist, was born shortly after the Civil War and lived a troubled life in and out of New Orleans dance clubs. By his early 30s, he was in a mental asylum, so much of the movie imagines his career. An early scene shows a picnic in a public park with a tuxedoed band playing the classic music of the time. Bolden is depicted as literally parachuting into the scene from a hot air balloon, playing as he falls.

MARSALIS: It didn’t happen in real life.

CORNISH: (Laughter) OK.

MARSALIS: But I’m sure it’s something that a manager would suggest…

CORNISH: (Laughter).

MARSALIS: …Something of that level of absurdity. However, the dynamics of the picnic are accurate. It was John Robichaux’s orchestra.

CORNISH: So he was a bandleader at that time.

MARSALIS: He was a bandleader at that time and a rival of Buddy Bolden’s.

CORNISH: And they are very formal, right? What are the elements of the music that we hear from the orchestra in that scene to start before Bolden comes?

MARSALIS: They’re playing straight American popular songs.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “BOLDEN”)

MARSALIS: But it’s not like they play stiff or that they were musicians who didn’t have incredible musicianship. They played with a great deal of feeling. It’s just they did not improvise. And Buddy Bolden represents the kind of wild, free spirit in which he did represent an entire new way of playing music. But the tendency is to denigrate Robichaux’s musicians and to make them seem as if they half-played the music that they played.

CORNISH: Interesting ‘cause when Bolden enters the scene…

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “BOLDEN”)

CORNISH: …And his band pulls up and it’s this freewheeling performance, you have the call-and-response elements people are familiar with now.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “BOLDEN”)

UNIDENTIFIED ACTORS: (As characters, singing) Hey, Buddy Bolden.

CORNISH: But I notice you have these two songs speaking to each other in a way.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “BOLDEN”)

MARSALIS: Yeah, because I have respect for Robichaux’s way of playing also. I just think the improvisation was too much. It was such a new thing, and Buddy Bolden himself was such a magnetic personality and genius as a musician that when you heard his sound, it was overwhelming. It was so dense and infectious that Robichaux just – his style couldn’t compete with Buddy’s style.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “BOLDEN”)

CORNISH: I want to talk about this idea of what made his improvisation so groundbreaking in that moment and why people kind of look to him as the person who was the kind of father of jazz. How striking was that improvisation?

MARSALIS: Buddy Bolden was like Prometheus. He was bringing fire, and he also synthesized the styles that existed at the time. So he could play sweet on a waltz. He could play pretty melodies. But he could also holler and shout like a sister in church. And he was so provocative as a musician. And his hearing was so clear. And as one lady at his time said, every time Bolden played, his heart broke so that he was the type of musician whose sound had the depth of human feeling that touched listeners, and they didn’t forget that sound. That sound put a healing on them.

CORNISH: Is there a song you think that really showcases that spirit where you try to really show the audience that kind of playing?

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “BOLDEN”)

MARSALIS: “Come On Children,” the first song, like, in the way that I’m playing, the fanfares and the type of lead trumpet that I’m playing. I’m trying to be very authoritative and definitive.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “BOLDEN”)

MARSALIS: He played very loud.

CORNISH: Yeah.

MARSALIS: He played with a lot of energy.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “BOLDEN”)

MARSALIS: And I’m trying to play fanfares, which is the basic thing trumpet players do.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “BOLDEN”)

MARSALIS: I also hold one note to the end of my breath. I try to just – just the kind of extremes I feel that he probably played with. Then I try to play a good lead. (Vocalizing).

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “BOLDEN”)

MARSALIS: It’s a little kind of blues riff ditty like what they would play at that time.

CORNISH: I have to say. How do you do that when you haven’t actually heard the person? Like, your descriptions of his music are so vivid, but we actually don’t know what he sounded like.

MARSALIS: First I make certain assumptions. Like, first I assume that he really could play.

CORNISH: (Laughter).

MARSALIS: He was called King Bolden.

CORNISH: Yeah.

MARSALIS: He wouldn’t have been called King. The second is I composite the three great cornet players who we have recordings of that were influenced by him. One is Freddie Keppard, great Creole cornetist who played in more of a ragtime style…

(SOUNDBITE OF FREDDIE KEPPARD’S JAZZ CARDINALS “STOCK YARDS STRUT”)

MARSALIS: …Bunk Johnson, who was a much younger man but was influenced by Buddy Bolden and played with a very smoky sound and played a very straight lead.

(SOUNDBITE OF BUNK JOHNSON’S “LOW DOWN BLUES”)

MARSALIS: And the third trumpet player is King Oliver.

(SOUNDBITE OF KING OLIVER’S “SPEAKEASY BLUES”)

MARSALIS: From King Oliver, you get the kind of dignity ‘cause King Oliver played with a lot of dignity but also created a lot of vocal sounds.

(SOUNDBITE OF KING OLIVER’S “SPEAKEASY BLUES”)

MARSALIS: So I put those three styles together, and I figured, OK, these three musicians were all influenced by Buddy Bolden, so they took an aspect of Bolden’s personality to construct their playing. So Bolden could play better than all three of them.

(SOUNDBITE OF KING OLIVER’S “SPEAKEASY BLUES”)

CORNISH: The film also depicts all of the struggles that African Americans are going through in that period of time, especially for someone like Bolden, who apparently suffered from mental illness, right? He died in a mental institution…

MARSALIS: Yeah.

CORNISH: …In 1931.

MARSALIS: Yes, he did suffer from mental illness.

CORNISH: And he inspired so many jazz greats. Why do you think in a way his history was lost to the mainstream?

MARSALIS: The musicians knew about him, but there have – has always been an attempt to denigrate the greatest Afro American figures in terms of their – what their actual achievement is. And then there’s a lack of interest in the Afro American community itself for what – for their achievements. So the church’s stance on jazz was always it’s the devil’s music; we don’t want to hear it. Black universities and institutions, when they began to crop up, didn’t want to deal with jazz at all. They strictly dealt with classical music. Even in my father’s time, he said he would get thrown out of practice rooms at Dillard and at Southern University for trying to play jazz. So a figure like Bolden would be overlooked.

(SOUNDBITE OF WYNTON MARSALIS’ “TIMELESSNESS”)

CORNISH: You’re such a decorated performer and artist. I know you were the only artist to win, for instance, like, a jazz and classical music Grammy in the same year. What do you think Buddy Bolden would have thought of where this music is now?

MARSALIS: I think, you know, for him to hear, like, Louis Armstrong’s playing or Miles’ playing or Dizzy Gillespie’s playing or – just so many great musicians. I can name them of all races. I happen to just name Afro American musicians, but if you take him listening to Paul Desmond or Dave Brubeck’s group or even fantastic high school students, I think he would be proud of it because the older musicians I knew – the older they were, the more they were proud of what had happened with the music.

CORNISH: Well, Wynton Marsalis, thank you so much for sharing this music with us. Thank you for speaking with us.

MARSALIS: Thank you so much, Audie. Thank you. It’s been a pleasure.

(SOUNDBITE OF WYNTON MARSALIS’ “BUDDY’S HORN”)

CORNISH: Wynton Marsalis wrote and performed the music for the film “Bolden.” The movie is out Friday.

(SOUNDBITE OF WYNTON MARSALIS’ “BUDDY’S HORN”)