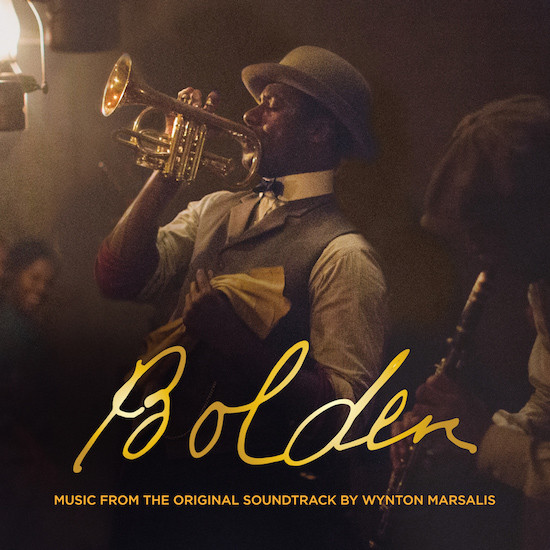

Director Dan Pritzker Talks About The Long-Awaited Musical Film ‘Bolden’

Coming out this week from Abramorama is the biopic Bolden, who created improvisation in New Orleans in the early 1900’s and pioneered the musical art form we now call JAZZ!!!

Directed by Dan Pritzker from a script written by Pritzker and David N. Rothschild, the film stars Gary Carr, Erik LaRay Harvey, Yaya DaCosta, Reno Wilson, Karimah Westbrook, JoNell Kennedy, Robert Ri’chard, Serena Reeder with Michael Rooker and Ian McShane.

The music was written, arranged & performed by multiple Grammy winner Wynton Marsalis.

The film is set in 1931 New Orleans, when Buddy Bolden, a long-time asylum inmate, hears the strains of a Louis Armstrong concert drift into his room from the radio in a nearby nurse’s station. The sound evokes memories of his long-forgotten youth as a ground-breaking cornetist, when he played and improvised his way to the forefront of a new musical style, ultimately creating what would evolve decades later into jazz.

Blackfilm.com correspondent Nicole Granston spoke with Pritzker about the making of this film.

Nicole Granston: Jazz is a well-known art form, but Charles “Buddy” Bolden, one of the founding pioneers isn’t. He’s sort of a myth. Talk about the dynamically immersive style and the film technique? What were you going for? What inspired you?

Dan Pritzker: When I first heard about Buddy Bolden, I was a musician. I still am. I was aware from the time I was a kid, of the through line from Louis Armstrong, Jimmy Hendrix, Jay Z, whomever you want to name. I don’t know the music you grew up on, but I would bet you that if we were listening to different stuff, it all came from the same place.

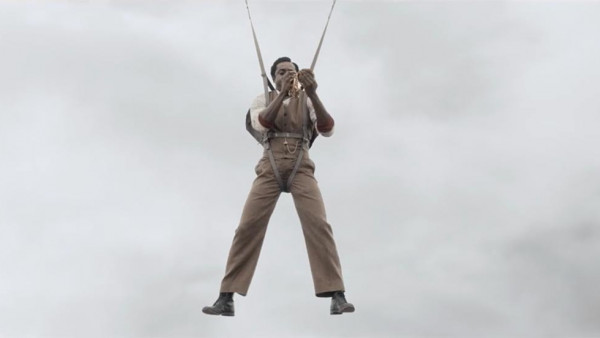

It struck me as poetic and tragic that there was this guy that flipped on the lights for all of us, and it was very moving to me that he changed the way we walked, the way we talked, the way we looked at time. I wanted to make an allegory about the soul of America, rather than a biography about the man because there’s not enough information about the guy to actually do a biography.

NG: You first heard the name Buddy Bolden, while you were touring with Sonia Dada, some 20 years ago. Since then you’ve made producing this film a passion project of yours. What captivated you about this story, this person?

DP: When this guy said, “Oh Buddy Bolden he invented Jazz, check him out”, it hit me immediately that this is American mythology. This is the tragedy and poetry of the country, that we would discard to anonymity the black guy that changed everything. Isn’t that typical American? It hit me at a very deep emotional level. As corny as it may sound, as soon as that guy said this to me, I didn’t think, “oh I’m going to make a movie”. I’d never made a movie before. I had no interest in making it. I’m not a cinephile. I like movies as much as the next person. I’m fanatic about music and have been since I was a little kid. Being able to close your eyes and just go inside of yourself listening to music, it was my spiritual center through my childhood and still is. Hearing about Buddy, made me say, I’d like to try and take a whack at telling the story my way. It allowed something open ended for me to use my own imagination. I would not have done a biopic or a story about Louis Armstrong because every minute of that guy’s life is so well documented, that you’re really just picking off anecdotes and stories. Bolden’s life was a much more opened ended story that allowed me to make something that sort of transcended the life of the man.

NG: Did you ever have any trepidation being a white person telling this story?

DP: Everyday, all day and even right now. (LOL) I say that but at the same time, not really because it’s just me. All the music that I love came from Black Americans. It has very much impacted my life that I don’t view it that way. I like what I like and it’s music. I have my own experience. I live my life.

NG: That explains a lot when looking at the movie. You as a musician, that’s how you see things. The rhythm, the sowing machines, the light; everything is playing off of each other. I assume those were all important elements in how you told the story?

DP: Also, to me, what was very important was that he was elevating women. He was seeing these working women in a more mythical, goddess type of way. They were giving him inspiration and he was giving back to them. It was a symbiotic relationship between them. That was an important element to me.

NG: Talk to us about the scene where Buddy is a little boy, hanging out at the factory where his mother worked and he’s laying on the floor. He’s listening to the humming and drumming, and the tic toc sounds of the machines. Is it safe to say you were trying to portray the fact that he learned rhythms and beats from those sounds and that music became part of his soul at that age?

DP: Whether it’s a piece of music, a painting or a film, when it’s successful, it resonates something in you, the viewer or listener. What I meant by a scene, honestly in my opinion is less relevant than how you received it because it’s no less valid or real.

NG: I’ve heard you’ve gone through many different versions to the point that you had to reshoot. What were you looking for that you finally found in this version?

DP: When I shot it the first time, I had never made a film before and it was a steep learning curve for me. I got home after shooting and I knew I didn’t have it, but I also knew I wasn’t done. I just had to go at it a different way, but I learned a lot and met all kinds of people, cast and crew. You start to get a feel for who gets your vision and who does not. I had to lick my wounds. It was hard for me to watch it after shooting the first version. I really wasn’t happy with how it turned out. I was dogged and went back out.

To your earlier question about being a white guy writing on this topic, I did not write the script in black vernacular. I knew I was going to be relying on the actors to bring that authenticity to the screen. We would talk about it. It was something very important to me. I wrote songs and other people sang my songs. The marriage between the voice and the song in your mouth, might work great, but in my mouth might not. So it was very important for the actors to bring everything to the table. By the time I got to the second shoot, I had people around me that were on the same page with me.

NG: What blew you away with Gary Carr?

DP: He’s just a different kind of guy. He’s a British guy that grew up in the theater world. He has enormous discipline but he doesn’t come from this sort of, macho American thing. He wasn’t out there being ‘jazz man’ he was more bookish, more introverted. I just thought it was a more interesting nuance to bring to the part.

I can tell you Gary is not the character he plays. In other words, he was in another place completely. A lot of times you work with actors who play characters who are extensions of them. He was really in a mode. When we came back for a week of reshoots in 2016 I could tell it was a little difficult for him. By that time he had been on a show on HBO and had done other stuff. It’s hard to turn that on and off, when you’ve had time away, but he’s brilliant. He’s a great guy.

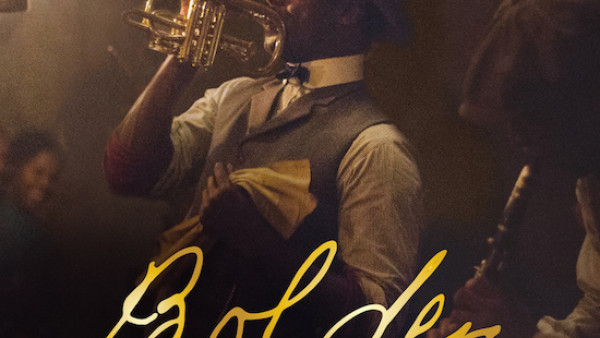

Gary is a great dancer. He did professional dancing in West End and other shows. He’s an athlete in the way a dancer is an athlete. He had terrific hand-eye coordination. Being able to learn how to convincingly play the Coronet is difficult. It’s a hard instrument. It’s not a long instrument, it’s right up on your face. It’s a very physical thing. He had to learn how to look real doing it.

by Nicole Granston

Source: Blackfilm