Wynton Marsalis Imagines Buddy Bolden

Nearly 120 years after his heyday in New Orleans, Charles “Buddy” Bolden, the cornet player and bandleader widely credited with inventing jazz at the dawn of the 20th century, may finally be about to get the attention he deserves.

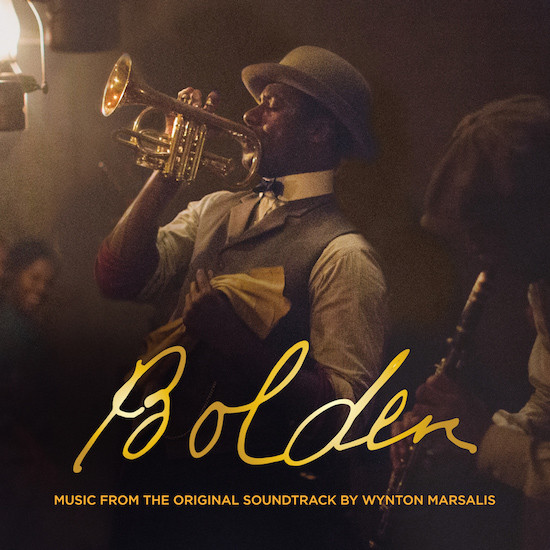

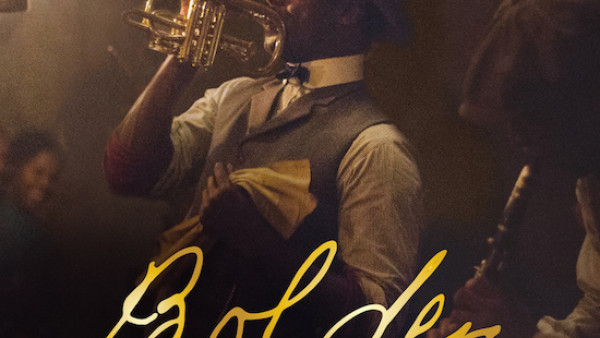

Bolden, an independent feature film by director Dan Pritzker with original music composed and performed by Wynton Marsalis, opens nationwide in May. The movie chronicles Bolden’s high times amid the racism and casual violence of New Orleans circa 1900, and the musical achievements that led to rock star-like adulation and his crowning as “King Bolden.” It also details his sudden, tragic downfall: In 1907, at age 29, Bolden was committed to the state insane asylum in Jackson, La., where he would spend the last 24 years of his life.

The film stars British actor Gary Carr in the title role, known to American audiences for playing the charming American jazz singer Jack Ross in Downton Abbey. Also in the cast are Yaya DaCosta as Bolden’s wife Nora, Erik LaRay Harvey as Bolden’s manager, and Ian McShane as the villainous Judge Perry.

For the soundtrack, Marsalis plays cornet and trumpet, backed by an all-star band including current and former members of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, in two distinct styles and aggregations: the six-piece Bolden band and the 10-piece jazz-age big band of Louis Armstrong, who was influenced by Bolden. The latter group performs “You Rascal You” and “Dinah,” among other songs, as Armstrong is uncannily impersonated on screen by actor/singer Reno Wilson.

“Bolden is really about the soul of our country,” Marsalis said by phone from his office in Manhattan. “It’s about the ‘black’ nature of being ‘white’ in America. We focus so much on division … we talk about whether a black person acts white … or whether a white person is imitating black. Now we have the whole ‘blackface’ scandal. This is something deeper in the soul of America. Whether you’re white or black, there’s a piece of Buddy Bolden in you.”

The relative paucity of historical facts about Bolden’s life, and the absence of any recordings of Bolden and his band, complicated the project. In the end, much of the film’s story and music amount to an educated guess. “The movie is mythology,” Marsalis acknowledged. “Some of it is true, some isn’t. It’s like many movies we’ve seen. Is The Godfather true? No. But yes. If it wasn’t true, it should have been true.”

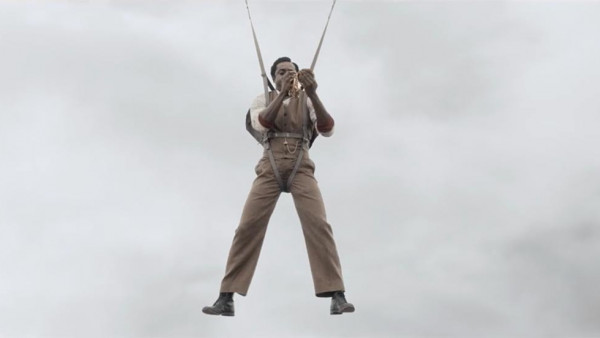

Some of the incidents in the screenplay were suggested by the biography In Search of Buddy Bolden by Donald Marquis (Louisiana State University Press), Marsalis said. For example, the film depicts Bolden and his band recording a wax cylinder. Such a recording has never been found, but the Marquis book presents anecdotal evidence for a session, attributed to Bolden friend and valve trombonist Willie Cornish. Another scene shows Bolden attracting attention to his music in spectacular fashion by parachuting out of a hot-air balloon while playing the cornet. As unlikely as this may seem, the book mentions several unverified—and probably unverifiable—stories of just such an incident.

There is also some controversy over the extent to which other musicians in New Orleans contributed to the birth of jazz by mixing marching-band music with blues and church music. “Bolden might not have been the only one, but he was the best one,” Marsalis said. “Like John Philip Sousa was not the only one with a marching band, but he was the best. You don’t get the name ‘King’ Bolden if you can’t play.

“I believe he invented something profound; that’s why they called him the king. The inventors always know more than the people who followed them. Like Giotto painted with perspective. The people who followed him years later did work better than him, but they didn’t say, ‘He didn’t really discover that.’ In orchestration, Haydn was the master; he invented those things… I never could understand why [anyone] would think that Bolden is not the master of what he invented. If Louis Armstrong thought he was the king, he was the king.”

The music of the Bolden and Armstrong bands in the film—and on a soundtrack album to be released on JALC’s Blue Engine label a month before the film’s release—certainly sounds authentic. If Marsalis didn’t break a sweat imagining the Bolden sound, it’s because he’s been steeped in New Orleans traditional music his whole life. “For the movie,” he said, “I combined the styles of three trumpet players who were influenced by Bolden: King Oliver, who played with a great sense of dignity; Freddie Keppard, who played with power and almost a ragtime feel, and was good at effects; and Bunk Johnson, who had a smoky tone and played very crisp, short phrases. I feel like Bolden’s actual style was probably greater than all three of them. Just like the many trumpet players that were influenced by Louis Armstrong—each player took an aspect of Armstrong’s personality to develop, but Louis played much more comprehensively than any of the players he influenced.”

Bolden had several tunes that were beloved by his fans; the most famous was what became known as “Buddy Bolden’s Blues,” later recorded by Jelly Roll Morton and dozens of other artists. Marsalis is sure he never played it the same way twice. “They were not reading music. They had tunes, then they played off them and improvised. He’s not ‘King Bolden’ because he played parts well. It’s because he was inventing stuff and coming up with new ideas all the time.”

The story that the movie tells of Bolden’s life and tragic trajectory is harrowing, yet most of the music is joyous. It makes for a strange dichotomy of feeling, Marsalis agreed. “This is a concept that is important to understand about the blues. When you’re having a hard time in your life … you don’t want music to drag you down. For you, a groove is an achievement of something transcendent. This thought that the only profound experience of life has to be death and transfiguration, or sorrow…” He trailed off, then added, “For you to grab joy out of that is a profound expression of your humanity. And that you can maintain your optimism without being naive about life—that is the joy of Buddy Bolden.”

by Allen Morrison

Source: JazzTimes