The Story Behind Wynton Marsalis’ Debut Album

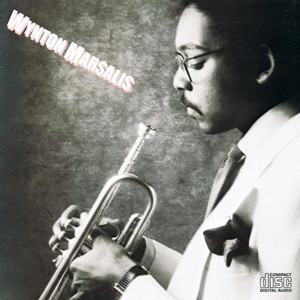

(photo: Michael Liewellyn © Sony Music Entertainment)

The impact of Wynton Marsalis’ self-titled debut is immeasurable. Released 40 years ago, the album introduced the wider jazz world to a preening trumpeter from New Orleans whose playing synthesized the styles of some of the instrument’s greatest innovators, such as Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, Fats Navarro, and Lee Morgan.

The prophetic Wynton Marsalis (Columbia) triggered a seismic shift in the jazz world, especially within the record industry. The album’s success reignited a strong interest among major labels in signing young jazz artists who were interested in playing acoustic postbop. The LP’s artwork came with another throwback: eloquent liner notes, written by Stanley Crouch. To bolster more excitement, Columbia released a complementary promo LP that featured Ed Williams interviewing Marsalis about the music.

Soon after Marsalis’ auspicious debut, Columbia signed other young jazz performers, some of whom were also from New Orleans. Other majors followed suit to help usher in the Young Lions movement of the 1980s and ’90s. Some naysayers lambasted the music of these young jazz artists as neoconservative. Nevertheless, it’s hard to deny that it rejuvenated the jazz ecosystem, which also encompassed the formal music education infrastructure, radio, venues, audience development, and the media.

You cannot discuss the Young Lions of the ’80s—who included trumpeters Terence Blanchard and Wallace Roney; saxophonists Branford Marsalis and Donald Harrison; pianist Harry Connick Jr., and the Harper Brothers—without mentioning Wynton Marsalis, because he became the movement’s de facto leader. Leonard Feather wrote in the Los Angeles Times that Wynton, “as a jazz soloist, [was] a symbol for the new decade.”

Mind you, other young artists (who were a bit older than Marsalis), such as saxophonists Ricky Ford and Chico Freeman and pianists James Williams and Hilton Ruiz, had recorded equally mesmerizing hard-bop and modal jazz LPs just a few years prior to 1982. But those LPs were released on smaller labels. They were not afforded the same amount of promotion and marketing muscle that Columbia offered Marsalis.

In the summer of 1979, Marsalis had arrived in New York and quickly electrified the jazz scene. At age 18, he’d enrolled at the Juilliard School, and soon after, he was working in the pit band of Sweeney Todd and the Brooklyn Philharmonia. Then he joined drummer Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, taking the trumpeter’s chair left by Valery Ponomarev. Soon everyone was talking about the new kid on the block from New Orleans who was playing hard-bop trumpet with technical virtuosity and clarity beyond his years.

Marsalis was touring with pianist and composer Herbie Hancock’s V.S.O.P. all-star ensemble (with bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams) in 1981 during the period when his debut album was produced. Previous editions of that band had featured Freddie Hubbard sharing the horn frontline with saxophonist Wayne Shorter, but neither Hubbard nor Shorter was scheduled to play with Hancock for an upcoming tour of Japan and the U.S. Dr. George Butler, executive producer and A&R director for Columbia, recommended that Hancock check out Marsalis, whom the label had recently signed. Blown away by what he heard, Hancock recruited the trumpeter for his tour.

Balking at Jazz-Funk

When Butler began working with Marsalis, he wasn’t quite sold on recording a straight-ahead jazz album. Butler initially saw Marsalis as a great potential competitor for fellow trumpeter Tom Browne. Although Browne’s GRP/Arista albums demonstrated his ability to play hard bop on a few cuts, it was his crossover jazz-funk classics like “Funkin’ for Jamaica (N.Y.)” and “Thighs High (Grip Your Hips and Move)” that made him a household name. The first tune reached No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot Soul Singles chart, while the latter reached No. 4.

Marsalis had played in funk bands while growing up in the Crescent City. But as a solo artist, he defiantly didn’t want to go Browne’s route. “I was a typical Black kid who grew up in the 1970s with a rudimentary knowledge of jazz,” Marsalis says. “I was like everybody else—someone who mainly listened to pop and funk music. But I knew that funk was different from jazz. So when people were trying to tell me that it was the same thing, I knew too much about funk to buy into that argument.”

Jazz pyrotechnics weren’t the only thing Marsalis brought to the Big Apple; with them came a kind of braggadocio that people now associate with heavy-hitting battle rappers. In hindsight, he acknowledges his disrespect for Browne’s artistic choices. He also recalls encountering Browne at the Red Rooster jazz club in Harlem and deciding to challenge him on the bandstand during a jam session. “[Browne] put his foot in the crack of my ass,” Marsalis laughs. “He absolutely played way more trumpet than I did. He ran me out of the club.’”

Another interesting sidenote is that Marsalis played with Browne on a couple of tunes on Fuse One’s obscure 1981 CTI LP Silk. It was an all-star affair with Stanley Clarke as musical director; the ensemble included some cream of the jazz-funk crop, including drummer Ndugu Chancler, keyboardist Ronnie Foster, guitarist Eric Gale, and bassist Marcus Miller, among others. Nevertheless, the photograph of the group inside the LP’s gatefold conspicuously does not feature Marsalis.

Marsalis stuck to his guns and convinced Butler to allow Hancock to produce his album. Even though Hancock had successfully straddled a pioneering career in both acoustic hard bop and experimental electric jazz fusion, he encouraged the trumpeter to make the album of his choice.

“Enharmonic Modulation”

“I learned a lot from Herbie, Ron, and Tony, just from being on the road,” Marsalis says. “They knew by the end of the summer that I wasn’t going to be a funk musician. I wanted to learn how to play jazz.”

After Hancock stepped into the role of producer, he advised Marsalis to write his own compositions and arrangements. “[Herbie said,] ‘Don’t ask me to harmonize your music and all this other stuff just because I have some harmonic sophistication,’” Marsalis recalls. “‘You need to come up with concepts.’”

Somehow, Marsalis’ “concept” for his music became vaguely known as “enharmonic modulation.” It sounded brainy and the powers that be at Columbia loved the ring of it. Thing was, “enharmonic modulation” meant very little.

“Wynton, being the beautifully sarcastic jackass that he is, told Columbia Records that he’d been working on this concept called ‘enharmonic modulation,’” saxophonist Branford Marsalis says. “Wynton said, ‘We will be playing in G-sharp major and then we will modulate to A-flat major. And no one would see it coming.’

“Well, enharmonic modulations or chord changes—sharps and flats—are used [only] to depict the direction of the notes [within a given key]. A-flat and G-sharp would be the exact same note. [Whether that note is written as A-flat or G-sharp depends entirely on the key that a piece is in.] So, there is no such thing as ‘enharmonic modulation’ because A-flat major is the same as G-sharp major. But [Columbia Records] didn’t know it. They thought it was great. Wynton was just messing with them.”

Big Brother

Marsalis recorded half of his album in Japan while still on tour with V.S.O.P. He insisted that his older brother Branford join the sessions, which also featured Hancock, Carter, and Williams. Branford Marsalis remembers being in awe of the major-league talent playing alongside him. “I was super-intimidated by the sessions,” he recalls. “It was fucking Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams.”

Wynton remembers things differently: “When they heard Branford, they said, ‘Your brother plays better than you.’”

In Japan, the ensemble recorded a feisty rendition of Carter’s “RJ” and a pneumatic reading of Williams’ “Sister Cheryl.” They also recorded “Who Can I Turn To (When Nobody Needs Me),” a melancholy ballad composed by Leslie Bricusse and Anthony Newley, and “Hesitation,” one of the three originals written by Marsalis. The punchy staccato melody on “Hesitation” played in unison by the Marsalis brothers, which eventually developed into ricocheting banter, gives a great glimpse of the jostling energy that Wynton and Branford would generate on later recordings.

Further sessions occurred in New York City, where Marsalis played with pianist Kenny Kirkland, drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts, and bassists Charles Fambrough and Clarence Seay. Branford participated in these sessions too. Except for “I’ll Be There When the Time Is Right,” a suspenseful through-composed ballad written by Hancock, Marsalis composed the remaining material.

The album’s cracking opener “Father Time” is a quicksilver, multi-sectional original that finds the rhythmic impulse erratically shifting from 4/4 swing to 6/8 African swing to 3/4 waltz, while the Marsalis brothers unravel balls-to-wall improvisations brimming with sonic youth. On Marsalis’ “Twilight,” a capricious 14-bar midtempo blues extends over a bass vamp.

Marsalis says that when he wrote these pieces, his musical understanding wasn’t particularly advanced. “I didn’t know that much,” he says. “I knew rudimentary counterpoint; I knew some bitonal chords; I knew African 6/8 time, being from New Orleans; I knew modal jazz. And I knew that the blues were important.

“When I finished the record, George didn’t like it,” he adds. “If I have to be honest, George really didn’t like a lot of the music that I recorded. But he supported it.”

Listening to Wynton Marsalis now, the music still bristles with freshness, even though modern straight-ahead jazz has since evolved. The album peaked at No. 9 on Billboard’s Jazz Albums chart; it even reached No. 165 on the Top 200 albums chart. In December of 1982, DownBeat magazine featured the Marsalis brothers on its cover, after crowning Wynton “Jazz Musician of the Year.” DownBeat also named Wynton Marsalis “Jazz Album of the Year.”

Epilogue

That same year, Columbia released Fathers & Sons, a cross-generational straight-ahead album featuring the Marsalis brothers playing with their father, pianist Ellis Marsalis (along with Fambrough and drummer James Black), on side one, while tenor saxophonist Chico Freeman joined forces with his father, saxophonist Von Freeman (along with drummer Jack DeJohnette, bassist Cecil McBee, and pianist Kenny Barron), on side two.

Marsalis’ sophomore LP, Think of One, was released in 1983. It won him a Grammy Award for Best Jazz Solo. He also won a Grammy that year in the classical category for his 1983 LP Haydn, Hummel, L. Mozart: Trumpet Concertos. At the 1984 Grammy Awards ceremony, he made headline news by performing both jazz and classical music. That performance catapulted him into superstardom.

“I was proud of Wynton,” Branford says about his brother’s 1982 debut and subsequent career ascension. “We like to say, ‘Wish things into existence.’ But Wynton busted his ass. His achievements weren’t really a wish. Wynton came to New York and kicked the door wide open with his abilities. He won two Grammy Awards in 1984—one for jazz and the other for classical. Who the fuck does that?”

By John Murph

Source: JazzTimes