Wynton Marsalis’ Violin Concerto: Beyond Category

DIGITAL REVIEW – It was Gunther Schuller who coined the term “Third Stream” in 1957 to denote a fusion of jazz and classical music. When he became head of the New England Conservatory, he even created a Third Stream department. But while everyone understood the general idea, finding a precise definition has proved elusive. For example, while most people would include improvisation as an essential ingredient of jazz, there are plenty of jazz-influenced classical pieces, e.g. Rhapsody in Blue, that have no improvisation at all. Are they really jazz? Is improvisation really an essential component of jazz? Lots of questions. Not many answers.

Wynton Marsalis is a musician who is the very incarnation of Third Stream. He was born in New Orleans, the birthplace of jazz, studied jazz with his father Ellis, a noted jazz pianist, and classical music at school. At 17, Wynton was the youngest musician admitted to the Tanglewood Music Center. He studied at Juilliard and planned on a career in classical music while still playing jazz trumpet with groups such as the Art Blakey big band. For many years, he alternated between recording the major trumpet concertos with leading orchestras while becoming one of the greatest jazz musicians of his time.

Still later, Marsalis turned to composition and, not surprisingly, wrote works that were clearly influenced by both jazz and classical music. As Marsalis has put it in liner notes of his latest recording, “finding and nurturing common musical ground between different arts and musical styles has been a lifetime fascination of mine.” But this is easier said than done.

In the case of his new Violin Concerto, as Marsalis sees it, the biggest challenges are “how to orchestrate the nuance and virtuosity in jazz and blues for an ensemble not versed in those styles (a technical issue); and how to create a consistent groove without a rhythm section (a musical/philosophical issue).”

The Marsalis Violin Concerto is a substantial and sophisticated piece lasting more than 40 minutes, or about the same length as the Beethoven or Brahms concerto. For the most part, the jazz elements are so thoroughly integrated into the very heart of the piece as to be almost unrecognizable as jazz. The violin is not a common jazz instrument – Joe Venuti and Stephane Grappelli are notable exceptions which prove the rule – and in the Marsalis concerto the violin tends to speak through its traditional classical persona. For Marsalis, that is not a limitation but an opportunity to expand the instrument’s possibilities to encompass jazz and to embrace its country cousins and the vast literature of fiddle music from around the world.

The Violin Concerto is in four movements: “Rhapsody,” “Rondo Burlesque,” “Blues,” and “Hootenanny.” In his notes, Marsalis uses metaphor to describe the music. The first movement, for example, “is a complex dream that becomes a nightmare, progresses into peacefulness and dissolves into ancestral memory.” That’s not much to go on for anyone trying to follow the thematic structure of the piece. But it is highly expressive and engrossing music. Toward the end we hear echoes of a march, “ancestral memory” – perhaps for Marsalis a childhood memory of a funeral procession in New Orleans?

The second movement draws on the wilder side of New Orleans, as Marsalis put it, “jazz, calliope, circus clown, African gumbo, Mardi Gras party.” The music here is raw and raucous and like nothing else ever heard in a violin concerto. The third movement is titled “Blues,” and it is exactly what jazz musicians always intended their music to be: the very incarnation of sadness beyond words. Lots of blue notes here. Is it jazz? Yes, but it is also music “beyond category,” as Duke Ellington liked to say.

Finally comes a barnyard throw-down titled “Hootenanny.” Fiddling from rural America transformed into art music of the highest and most joyous order.

Marsalis has given us a major work in his Violin Concerto woven from elements of American jazz and folk music. But it could never be mistaken for the work of Aaron Copland. Marsalis has a far deeper understanding of the roots of American music; he has lived it and played it in all its rawness and sophistication. This is a piece with so many layers of thought and feeling that only repeated hearings will reveal the full extent of its structure and meaning.

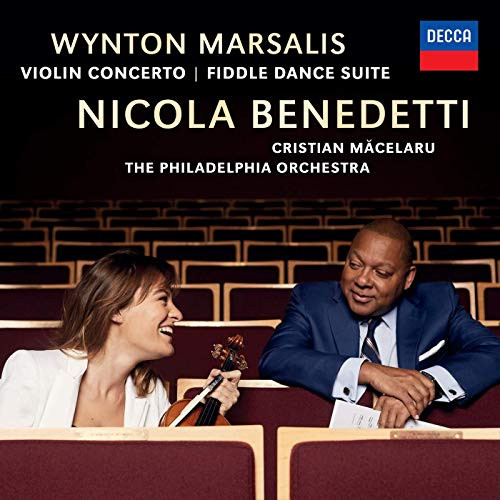

Violinist Nicola Benedetti worked closely with the composer to bring this piece to life, and she plays brilliantly. Her work, too, will have to be studied closely to appreciate the artistry she has brought to this remarkable composition.

The other piece on this CD, Marsalis’ Fiddle Dance Suite for Solo Violin, might be considered a companion piece to the Violin Concerto. It also was written for Benedetti, and it also draws heavily on traditional fiddle music from Ireland, Scotland, and America. Some of the source material is early jazz and some has more modern jazz added onto it, not to mention rhythmic complexity that turns some of these simple tunes inside out. The five movements have titles that denote their origins: “Sidestep Reel,” “As the Wind Goes,” “Jones’ Jig,” “Nicola’s Strathspey,” and “Bye-Bye Breakdown.”

This last movement draws on the same barn-dance fiddling that is the basis of the last movement of the Violin Concerto. Except that it goes the concerto one better in requiring the soloist to both fiddle and stomp at the same time. Johann Sebastian Bach may have set the standard for unaccompanied violin music, but Wynton Marsalis has shown that there is plenty of life left in the old forms.

By Paul E. Robinson

Source: Classical Voice North America