Wynton Marsalis, The Linus’ King

“When I was a boy, the only time you would hear jazz on television was when Charlie Brown came to town,” recalls trumpeter Wynton Marsalis in the liner notes to his new recording, “Joe Cool’s Blues” (Columbia). The music that the late pianist Vince Guaraldi composed for the “Peanuts” television specials in the ’60s piqued Marsalis’s interest not only because it was “upbeat and happy,” but because “we were aware that my father knew him. So that made us think our father was important.”

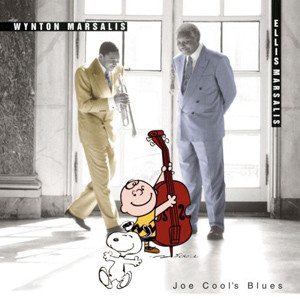

The impact Guaraldi’s quirky themes and musical caricatures had on the Marsalises’ New Orleans household couldn’t be more apparent on “Joe Cool’s Blues.” Reflecting abundant affection for the creations of Guaraldi and, of course, cartoonist Charles M. Schulz, the music radiates great warmth, color, playfulness and poignancy without ever devolving into a purely sentimental journey. Fittingly, Wynton shares the album’s billing with his father, pianist Ellis Marsalis. The 13 performances are primarily divided between original music and septet settings devised by Wynton, and arrangements of Guaraldi’s music performed by Ellis’s trio, featuring bassist Reginald Veal and drummer Martin Butler.

Apparently, Wynton couldn’t resist the opportunity to score Guaraldi’s contagious “Linus & Lucy” for four horns and a rhythm section. The album opens with this cool confluence of brass and reeds, emphatically punctuated by pianist Eric Reed’s right hand, Marsalis’s tart trumpet and trombonist Wycliffe Gordon’s smeared tones. Reed eventually breaks ranks with a cascading blues interlude of his own design before the familiar melody returns, more buoyant than ever, in the final chorus.

As the album unfolds, nothing Wynton contributes as a writer is as memorable as this classic jazz portrait, and yet his compositions can be wonderfully expressive. He often combines engaging themes with sophisticated arrangements celebrating his Crescent City roots. Whimsical melodies, vibrantly honed ensemble passages, crisply articulated solos and drummer Herlin Riley’s deft touch distinguish many of the performances, beginning with “Buggy Ride” and “On Peanut’s Playground.” Other tunes, particularly “Wright Brothers Rag” and “Why, Charlie Brown,” take full advantage of the septet’s polyphonic verve and unusually broad tonal resources, which are expanded by mutes and plungers.

Alas, the septet is no more. Marsalis has since disbanded the group in favor of a quartet, and no doubt the new ensemble will produce a lot of enjoyable music. But it’s hard to imagine the trumpeter not missing the kind of color and vitality generated by the septet’s front line on this session.

The performances by Ellis Marsalis’s Trio are true to the spirit of Guaraldi’s small combo recordings, but they’re also far more soulful and swinging. The family patriarch makes his entrance by hammering out a rhythmically infectious version of “Peppermint Patty,” in which funk and blues happily commingle, and then casually infuses “Oh, Good Grief” and other tunes with an earthiness and elegance that’s sometimes more evocative of Count Basie’s canon than Guaraldi’s. For “Little Birdie,” Ellis heads straight to New Orleans for support and inspiration, adding singer Germaine Bazzle and four horns (including his son Delfeayo on trombone) to the trio’s insinuating R&B groove. (To hear a free Sound Bite from this album, call 202-334-9000 and press 8141.) Eric Reed’s “The Swing and I”

During his tenure with the Marsalis septet, pianist Eric Reed, who will perform at Blues Alley on April 5, found time to record on his own and with very promising results. His latest album, “The Swing and I” (MoJazz), includes 18 selections, 15 of them original compositions. The most ambitious work is Reed’s “The Gemini Suite,” a 12-minute triptych that attests to his formidable technique and his developing skills as a composer and arranger. Colorfully contrasting rhapsodic swing, hard-bop flights and brush-stroked balladry, the three movements set the stage for the many mood swings on the remainder of the album.

As on his previous recordings, there’s no mistaking Reed’s influences. In fact, there’s an almost defining moment here when Reed, bassist Ben Wolfe and drummer Gregory Hutchinson salute pianist Ahmad Jamal with a nearly nine-minute version of “Ahmad’s Blues.” The leisurely treble runs and insistent trills, the aggressive gospel-inflected chords and rippling flourishes, the sudden and often bold contrasts in dynamics — all of these elements point to the profound effect Jamal’s music has had on Reed as a pianist, composer and arranger.

When the album comes up short, it’s usually because Reed’s writing fails him — the brief interludes devoted to jazz greats are sketchy at best — or because he seems a bit too enamored with the kind of jazz-funk that Ramsey Lewis popularized in the ’60s.

by Mike Joyce

Source: The Washington Post