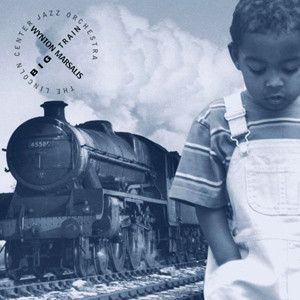

Marsalis’s ‘Train’: It’s The Rail Thing

The Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra’s performance at Constitution Hall on Friday included the Washington premiere of Wynton Marsalis’s first major composition since “Blood on the Fields” was awarded the Pulitzer Prize last year. The new work, “Big Train,” is a panoramic portrait that suggests a romantic bygone era of outward mobility and discovery, couched as a coast-to-coast journey through the American psyche. At the start, Marsalis, director and conductor of the 16-piece orchestra, warned, “It’s big and it’s long . . . and it’s going to feel like a classical concert!”

He might have added that “Big Train,” which received its world premiere at New York’s Alice Tully Hall just two nights before, is ambitious without being anywhere near as emotionally intense as “Blood on the Fields.” At 50 minutes, it is an essentially upbeat excursion that occasionally wanders off the rails and might be more effective with the elimination of a few excess baggage cars between its engine of roiling rhythms and caboose of majestic melody.

As might be expected, “Big Train” starts slowly and picks up steam, its early segments suggesting both the gradual powering-up of engines and the jubilance of passengers embarking on their journey. The work is continuous, and Marsalis’s voicings and textures effectively suggest passage through an ever-changing countryside. You can hear whistles blowing, wheels churning, engines clanking, sense the train’s lonely race through the cool night, its blazing lights like shooting stars along the horizon, or feel its last stop through the cooling-down cacophony as the brass and reed players sputter into the station on last breaths alone.

Part of the problem with “Big Train” is that it seems to have too many patched-together pieces, too frequent shifts in tempo, so that the most involving segments — a languorous ballad section toward the end, an engine-inspired showcase for drummer Herlin Riley, Marsalis’s own churning trumpet solo — clearly overshadowed the work as a whole. “Big Train” is cohesive but not consistent; it sprawls.

The first half of Friday’s program was a mixed bag of classic jazz works reflecting the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra’s prime directive: to preserve and promote the jazz canon as symphony orchestras do the European classical repertory. That the orchestra is informed and inspired by the past, not straitjacketed by it, was evident in vibrant readings of works by Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, Thelonious Monk, Frank Foster, Louis Armstrong and Marsalis.

The evening kicked off with Ellington’s “Chinoiserie,” a vanguard brew of eclectic rhythms, dissonant exotica and evocative lyricism, the last courtesy of tenor saxophonist Walter Blanding Jr. The sassy sway and swagger of Armstrong’s “Tight Like This” provided one of the few showcases for Marsalis’s growling, smear-stained trumpet. Marsalis spent the evening sitting in the trumpet section, calling out tunes and serving up convivial explications, while the orchestra charged on.

Frank Foster’s “Blues in Frankie’s Flat” had the fulsome, brassy bounce one associates with the Count Basie Orchestra it was written for. The evening’s most glorious moment came with Strayhorn’s “Isfahan,” a liquid ballad set amid gorgeous voicings and given a luminous reading by alto saxophonist Wess Anderson, whose playing at times felt like a soft breeze passing over glowing embers.

by Richard Harrington

Source: Washington Post