Big Band, Big Premiere, Big Tour, Big Marsalis

Wynton Marsalis and the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra have spent the last several months touring the world, and on Thursday night at Alice Tully Hall, over several hours of technically perfect playing, it showed. Mr. Marsalis and the orchestra, who will be performing again tonight as part of Jazz at Lincoln Center, were completely at ease moving through difficult music; the sharp juxtapositions Mr. Marsalis throws around in his pieces were never forced, and horn and percussion riffs were tossed in the air with the precision of a piece of industrial equipment stamping out a metal part. And at least one musician nodded off to sleep.

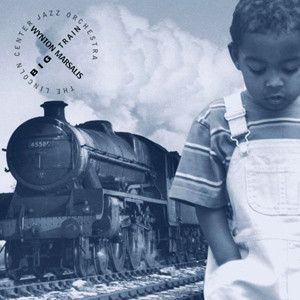

Mr. Marsalis, artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, spent the evening performing his own compositions, starting with portions of a suite, ‘‘Sweet Release,’‘ interspersed with tunes from the suites ‘‘Blood on the Fields’‘ and ‘‘Jump Start.’‘ The second half featured ‘‘Big Train,’‘ an hourlong work built on the Americana of train sounds and reflecting the mobility of early American society.

The big band is Mr. Marsalis’s logical destination, and even during the world premiere of ‘‘Big Train,’‘ an ambitious piece that seemed to be half an hour too long, Mr. Marsalis showed his control over mood, conjured up by meticulous arranging tricks. It was perfect material for a jazz orchestra. He uses textures the way many composers use melodies, and through all his pieces he set vinegary dissonances against industrial rhythms.

Mr. Marsalis has clearly studied the way Duke Ellington controlled the rhythm section, and for every part of his suites he had the drummer, Herlin Riley, playing swing rhythms, tight and airless, or Afro-Caribbean rhythms, or shuffles. The tempos, often a bit slower than moderate, were almost archaic, a reminder of a more relaxed and sensuous time. On one piece he had sopranino and soprano saxophones and a flute play a melody; it was thin, reedy and distinct.

‘‘Big Train’‘ was a curious failure, curious because of its virtuosity. Mr. Marsalis spread train themes throughout the piece, the coarse dissonances of the whistles blowing, the repetitions of the train’s rhythms, its speeding up and slowing down. But he also skipped around, tossing in a bossa nova section for a minute or two, after which it vanished. It was as if he had packed together all the leftovers of his fertile mind and not really found a good way to underscore the strong parts or organize the suite in a musical instead of a literary way.

By the time the best part of the piece came along, a creamy set of melodies and a chant that ended the evening, so much material had whirled by that the various shards had all been diminished, regardless of their flawless execution. The first half was just as virtuosic, but it worked, and oddly it had almost no traditional solos. The improvisations were often polyphonic, with several instrumentalists playing at once, winding sounds together or contrasting the surface textures of their instruments.

Continue reading the main story

Mr. Marsalis was working with the orchestra as his brush and paints, and he was after something unconventional. Even without solos, the music reached all sorts of destinations, from humor to sensuality to gentleness. Finally, after the virtuosity of the conception was put aside, he came forward as an emotionalist, moved by history and by American themes.

by Peter Watrous

Source: T“he New York Times”:https://www.nytimes.com/1998/03/21/arts/jazz-review-big-band-big-premiere-big-tour-big-marsalis.html