Wynton Marsalis Says Cultural Con Jobs Began Long Before Trump

As for so many of us, the past several months formed a season of loss for Wynton Marsalis. His father, pianist Ellis Marsalis—who Wynton described on his blog as “a humble man with a lyrical sound”—died on April 1, at 85, from complications of COVID-19. One of his clearest mentors, the writer and critic Stanley Crouch, died on Sept. 16, at 74.

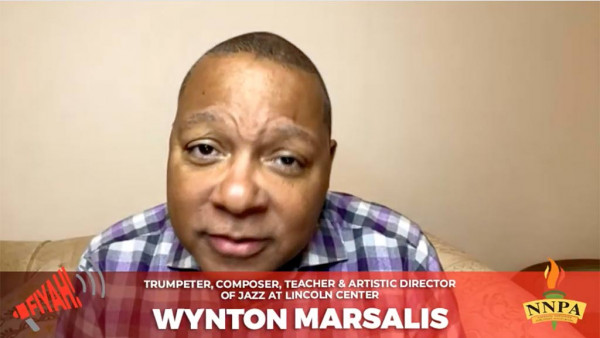

The celebrated trumpeter is, as are we all, caught in an extended period of estrangement—his last public performance with his orchestra was more than seven months ago. This new reality requires that Marsalis hustle harder and in new ways to keep his jazz orchestra active and to maintain the vitality of Jazz at Lincoln Center, the organization for which he has been the public face since 1987. “We have to be intelligent and nimble and committed and dedicated,” he told me of his role as managing and artistic director. “And we have to accept the position that we’re in.”

Shortly after the lockdown took hold, Marsalis began Skain’s Domain, a series of recorded Zoom conversations with other musicians “about how to stay connected, optimistic, and creative.” The day after his father’s death, he led 16 musicians through the first installment of Memorial For Us All, a digital Lincoln Center series meant as “a secular community remembrance.” This summer, a virtual 25th edition of Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Essentially Ellington High School Band Competition and Festival brought together 23 bands from around the world. This month the organization began “Live from Dizzy’s, streamed weekly Thursday evening jazz performances from its jazz club.

Lately, Marsalis has focused on a different sort of hustle—the central theme of The Ever Fonky Lowdown, the extended musical piece with narration that he first presented at Jazz at Lincoln Center in 2018 and has now released as a recording. “This is an international hustle, baby,” announces Mr. Game, the piece’s narrator and suave antihero, portrayed by actor Wendell Pierce. “It has played out many times across time and space and is not specific to any language or race. It takes on different flavors according to people’s taste, but always ends up in the same old place.” As a composer, Mr. Marsalis walks his central instrumental theme through several time signatures—4/4, 5/4, 6/8, and so on. With his libretto, he means to address the many ways in which he thinks we are being hoodwinked and are fooling ourselves.

In late August, as a guest via Zoom on Real Time with Bill Maher, Marsalis explained to the host, “We’re being hustled, but what will save us is collective creativity.” His new work, Marsalis said, “satirizes the things that divide us and allows us to see in ironic detail what separates us so that we can envision working with instead of against each other.” Which isn’t to say that everyone will feel galvanized by Marsalis’ polemical libretto: As Marsalis has many times in the past, here he casts rap largely as modern-day minstrelsy. Yet he also lands on familiarly chilling ironies, as when Mr. Game celebrates “freedom through constant surveillance and relentless security.”

In conversation, via Zoom, Marsalis talked about this curious moment in time, the timeless hustle that inspired his “jazz parable” and his hopes for the future.

The first question I ask any musician these days is, When was the last time you played before a live audience?

Man, I don’t even know. I think in February, in Spain, with the orchestra. That was the last real concert. But I also played at Smalls club, in Manhattan, in August with Joe Farnsworth, on his date. There were only a few people there, it was a virtual show, but if anyone’s in the room it counts as a gig. [Note: This month, Marsalis began to tour outdoor venues with a septet of orchestra members.]

Have you ever gone six months without performing before an audience?

No, not since I was 12.

What does that do to you?

We’re all struggling to survive in a variety of ways. But I’m working so much that I’m not thinking about it. We’ve got to keep our organization going. I’m not analyzing anything but the road forward. As a band, we meet once a week. We’re talking, and we’re doing things, we’re putting things up online. We’re acutely aware of the fact that we’ve missed playing with each other live, but we have to survive.

When did you compose the music and write the libretto for The Ever Fonky Lowdown?

Right before we performed it, in 2018. But I worked on the libretto for a long time before that because it’s easy for me to write music. A lot of the libretto comes from ideas that my little brother Ellis [Ellis III] and I had talked about for years, for decades.

What was the nature of those conversations?

We’d always just talk about what’s going on in the country, the hustle that goes on and on.

Donald Trump had already taken office when you wrote this. In your piece, Mr. Game says, “Success is in my middle name / I became famous for my financial twerking that showed folks how to make money without even the money working.” That sounds quite Trumpian…

It’s not about Trump. Well, Trump is one of the people, of course, but it’s also about Obama, about Clinton, and definitely about Reagan, who started a lot of these hustles. It’s about everybody who has been president since I’ve been conscious. Don’t reduce it to this president because when you do reduce it to him you let yourself off the hook. The corruption in America is on the left and the right. Mr. Game is not a left or right figure. This is the perfect time to say, this is not us. Let’s be something else. We need to correct ourselves.

You’ve referred to this piece as a satirical look at, among other things, “cultural corruption.” How would you describe the culture you think is being corrupted?

I’m talking about the symbolic ways in which we deal with important inflection points in our lives. So, what are those symbolic ways? How do we deal with death from a cultural standpoint? How do we deal with illness and sickness? How do we deal with courtship and romance? How do we deal with deep disappointment and sorrow? How do we deal with joy and celebration? How do we deal with our inner relationships, in communications with each other? And I’m speaking about cultural symbolism. Things that means something. It means something when every movie has a Black person as a criminal. That has a cultural meaning.

We’re either in a moment with promise for transformative change or not. Do you feel like that we are starting to move past harmful cultural symbols?

I can’t predict a future. I’m not going to talk in the first quarter about what we’re going to do in the fourth quarter.

To follow your metaphor, if this were football, how’s the game going?

It’s not going that good right now. We have a lot of evil, corrupt forces in the world, but there’s also a lot of force for good and people who want to treat other people with respect. And there’s a lot of people who want to see more equality, a lot of people working on behalf of that. I feel like it’s very important to affirm the millions of people who are doing that. I think about all of us are in a position to affect change. We’ve reached a crossroads, and not just in America but in the world. Awareness is the beginning of change, right? If you’re not aware, you can’t change. I mean for the The Ever Fonky Lowdown to be a blueprint for awareness.

Has the dimension of the hustle become greater lately?

No. I mean, it’s just more blatant. But, then again, is it more blatant than supply-side economics? That was blatant. Is it more blatant than junk bonds? Is it more blatant than, after the subprime scandal, when nobody went to jail and everybody who stole money got more money? That was all pretty blatant.

Is the game, the hustle, inescapable?

It’s escapable. That’s what we talking about, right? We can put people in jail. It’s possible to not be corrupt. It’s possible not to steal. It’s possible not to hold other people down.

How do we escape the hustle?

Mr. Game tells us at the end. He breaks the whole thing down for you. He’s trying to get people to understand that the energy you have to expend to hate people who already don’t have shit, well, you could be extending that on building something that will give both of you something. Mr. Game says to us that an indifferent government is wasting your time and money while you endorse tribal policies that violate your own self-interest as you swallow a fake binary—a narrative of Democrat versus Republican, white versus Black, man versus woman. These are games that play us as fools.

Will the coming election offer some escape from that?

The question for this election is, Will the large group of white voters that have been manipulated through the years by the fake lure of racism realize that money and power is the issue and the people they have been directed to attack have neither.

You dedicated a two-part ballad here to Fannie Lou Hamer, a heroine of the Civil Rights movement who is not as well-known as she should be. Where did you first learn of her?

From my momma. My momma loved her. When she talked about Fannie Lou, it was like somebody who was talking about a favorite musician. “Child, Fannie Lou is for real,” she’d say. “Watch what Fannie Lou is doing, listen to what she says.” I have finally arrived at an age where I have started to bring back the things my mother introduced to me.

When the city of New Orleans removed four Confederate monuments, then-mayor Mitch Landrieu referred to conversations with you. What did you say?

Well, our conversations were just like regular middle-aged conversations, like what me and you would have—about children, family, and such. It was not a political conversation. Just two old trumpet players sitting up one morning, just before I was leaving town. We just started talking about the city’s tricentennial. And I just told him, these statues, especially the statue of Robert E. Lee in the center of the city, needed to come down. It’s like a curse over the city. And he said he was looking into it. I didn’t think I would hear back from him. Then he said, Man, you know I have jurisdiction over these damn statues!

What did it mean to you to see those four statues come down?

Frankly, I would rather see us teach everybody who moves to that city the significance of our cultural traditions, the second line and all the rest. But I was happy to see signs of the Confederacy come down. They lost, they shouldn’t have statues. Do I feel like it makes a difference symbolically whether some losers have a statue in the middle of the city? Yeah, it makes a difference.

Do you have the feeling that a piece such as the one you’ve just released can make a difference in our current political climate, and in the world at large?

I always have felt that way, my entire time of playing.

Right now, as the disorientation and pain of a pandemic continues with no clear end in sight, as an arts administrator, how do you deal with that uncertain future for Jazz at Lincoln Center?

We plan, we stay active. We reach out to friends and people all over the world to help support us. We get our younger people involved in what we’re doing. We make sure that we are very responsible with our resources and we continue to be relevant through the quality and depth of what we do. And we come together and become closer as a staff and an orchestra and a board. We challenge each other to see if we are who we say we are, and we will see. Nobody knows where this is going to go, but we have to be intelligent and nimble and committed and dedicated. And we have to accept the position that we’re in. And as much as we have to, and we have to try to create another reality that will allow us to survive and indeed, to thrive—if not now, when we come out of this.

Do you think that the landscape for music and for performing arts in general can ever return to how it used to be?

I want it to be better than what it once was.

By Larry Blumenfeld

Source: The Daily Beast