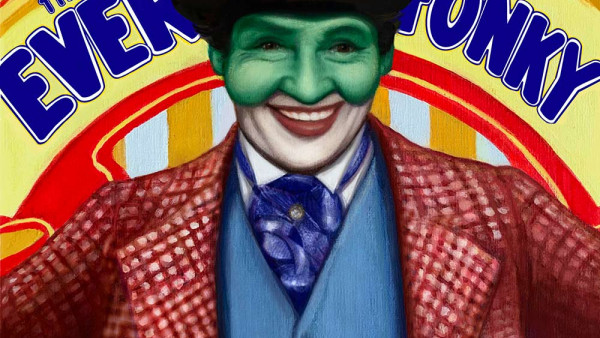

Wynton Marsalis tackles racial injustice, social decay in the new ‘The Ever Fonky Lowdown’

CLEVELAND, Ohio — Once a decade since the mid-80s, Wynton Marsalis steps out a bit and takes his music into the realm of social commentary.

He does it well, too — as if there would even be a question. The acclaimed trumpeter and educator’s “Blood on the Fields” in 1996 was the first jazz composition ever to win a Pulitzer Prize. And the rest of the oeuvre — 1985′s “Black Codes (From the Underground),” “All Rise” in 2002 and “From the Plantation to the Penitentiary” in 2007 — have been landmarks in their own right.

This year Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra are back with “The Ever Fonky Lowdown,” a dramatic and wickedly satiric piece that stares down issues such as racial injustice and inequality, corruption and the decay he sees in societal values. Through the eye of its narrator, Mr. Game (Wendell Pierce), and vocalists such as Christie Dashiell, Ashley Pezzotti, Camille Thurman and Doug Wamble, it couldn’t fit the times better if it was written yesterday. During a laudatory 40-plus year career Marsalis is no stranger to making major statements, of course, and with “The Every Fonky Lowdown” he’s as unapologetic, and as accomplished, as he’s ever been…

“The Every Fonky Lowdown” is a topical piece, of course, but it’s kind of stunning just how on-point it is for right now.

Marsalis: From a timing standpoint, yes — the pandemic and the social unrest, the division and inequalities, financial and political, the machinations. All these things we’ve been seeing for the past…if you talk to really old people, they’ll say it was always like this. But we’ve seen it. It’s all part of it. It’s always underneath the surface, and now it’s been brought out above ground. So in that way, it became kind of a perfect time for it to come out, even though we thought it was going to come out earlier.

What is it trying to say?

Marsalis: It’s supposed to be a blueprint to help us decode the hustles that keep us fighting. It’s trying to show the system that’s in place to keep us apart and turn us against each other. People need to recognize that’s what we’re dealing with and get out of that cycle and fight it. It’s a scary thing.

What makes jazz such a good vehicle to express this kind of message?

Marsalis: It’s an art form that has always been engaged with freedom and American democracy. Artists of all races — from Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Dave Brubeck, Dizzy Gillespie, Charles Mingus, Max Roach, early Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman…I read an interview once with Gene Krupa, talking about race relations in the 1930s. We have this history of engagement with our culture. It became a little less after the Civil Rights movement, but we still had some hangers-on. Charlie Haden was always good for speaking about it. Christian McBride wrote a piece. But in a strange way jazz became much less socially active in a way, and you wouldn’t say it’s a prevalent spirit of the music in this time.

That seems like a curious de-evolution.

Marsalis: I know. The music is sophisticated, and it also comes from a class that was put in a position of being enslaved. I think we got to the point where jazz (musicians) became kind of an elite class, and it wasn’t ever an expectation that some revelation about that way of life would come from that class. To acknowledge the message of jazz and the realizing of jazz came from a condition of those who were in slavery and the aftermath of slavery was not their personal condition, but it was a system that they came from. We still are not ready to talk about that.

What was your path into these socially conscious musical pieces?

Marsalis: It actually starts, in an ironic way, when Kurt Masur, the conductor of the New York Philharmonic — he’s a trumpet player, too — asked me in 1989 if I would write a piece for them. I had to laugh; I said, “I’d never written for a big band at that point, so I’m not gonna write for the New York Philharmonic!” But he made me think and wonder if I could learn enough to write for an orchestra. “Blood on the Fields” was my first piece for big band. Then I would see Kurt on the campus of Lincoln Center, and he would say, “My friend, are you still afraid to write for the New York Philharmonic?” (laughs) So, yeah, he was the one who kinda started me…and in ’99 he said, “I want you to write a piece for the New York Philharmonic” (which became “All Rise”).

On “The Ever Fonky Lowdown” you employ a narrator, Mr. Game — not a particularly savory character, but he gets the point across.

Marsalis: He’s kind of a mix between a preacher, a politician, a lawyer, a businessman, a street hustler…He speaks both high English and street language — some of what he says comes from Shakespeare. He’s jive but he really knows how to draw people in and keep them hanging on his every word. I spent a lot of time writing those parts ‘cause that’s not really what I do; I write music, you know? So, I developed very strong outlines and then worked on the words a lot. I mean, I do like to write. I like language. I guess I consider myself an amateur writer.

Are there other applications for “The Ever Fonky Lowdown” — a visual piece, perhaps, or a theatrical stage version?

Marsalis: I’m always amenable to work in different ways. I’ll collaborate with anybody. Right now, we’re not in a position to do anything that costs money, but it could be an interesting dance piece or something if somebody wants to take it on.

What are you working on now?

Marsalis: I just finished a suite of eight pieces, called “Democracy Suite.” I’m writing some pieces for other members of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Septet, and those of us who live in New York are gonna get together and play some socially distanced concerts. We hope people will come out and make space and have a good time. We’ve dealt with the limitations as best we can and tried to sound as good as we can and bring the joy and consciousness of the music. We’ll be safe, but people need to hear music. So that’s what we’re gonna do, just keep rolling and until we can get back to the way we were, or something like it.

By Gary Graff

Source: Cleveland.com