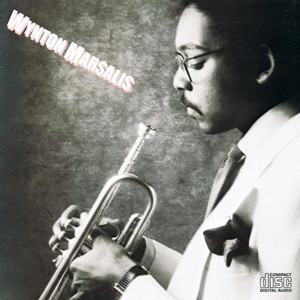

Wynton Marsalis: At 20, a master of jazz style

It’s seldom that any jazz musician – let alone such a very young, not yet widely known player as trumpeter Wynton Marsalis – gets a page to himself in People magazine. But early this year that’s where Marsalis was, under the banner “Personalities to Watch.”

As you might expect, the paragraph that ran alongside his picture emphasized “human interest” factor over music. Topping the list was Marsalis’ youth (only 20 years old, he is already a veteran of Herbie Hancock and Art Blakey’s bands).

Then came the “following in his father’s footsteps” theme [Ellis Marsalis, his father, is New Orleans’ premier pianist]; the news that our hero, a former Juilliard student, plays classical music as well as jazz; and the fact that Marsalis was given his first trumpet, at age 6, by no less a figure than Al Hirt.

Colorful stuff, I suppose, and it leads to thoughts of a new TV show titled “Jazz Musicians Do Amazing Things.” But the magazine story almost forgot to mention the one thing about Wynton Marsalis that is truly amazing: his ability to play the heck out of the trumpet.

Apply any standard that comes to mind – speed, range, cleanness of tone – and Marsalis is an astonishing technician, even when measured against such celebrated hotshots as Freddie Hubbard and Woody Shaw. [If you want in-person proof, drop by the Jazz Showcase in the Blackstone Hotel Wednesday through next Sunday where Marsalis will be perform with Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.]

“I know I can play fast and high,” he says, because I have practiced that. But that’s not what jazz is all about. Take Don Cherry, who is a phenomenal jazz trumpet player. He can’t really play the trumpet technically, but that makes him get down to the essence of the music, whereas I have so much technique that it gets in my way. I’ll just be playing stuff because I can play it, which distracts me from what I should be playing.

Sure, my technique helps me get over a lot of obstacles. But in the long run, those obstacles are the stuff I have to work on – melodic phrasing, using space, developing my ear and so forth. My biggest problem is figuring out what to play. So much stuff has been played already that it takes time to come up with something new.

People say I have too many obvious influences – Miles (Davis), Freddie (Hubbard), Clifford (Brown). Well, even though I know there’s stuff that I can do that none of those cats can do, I’m only 20. So if you’re listening to me to hear Miles, you’re going to hear Miles, and the same with Freddie and Clifford.

“Everybody comes from somebody, except for a few cats. Louis Armstrong sounded very little like King Oliver, and Duke Ellington was Duke Ellington. But cats like that are geniuses. I don’t have enough stuff behind me to say I’m playing more than Miles and everybody. No, man, that’s not how it’s done. You just have to wait your turn, play and learn.”

Speaking these words with the same urgency, speed and flair with which he plays his instrument, Marsalis is seated in the coffee shop of one of the hotels that ring O’Hare International Airport, waiting to rehearse for a performance that evening before a convention of jazz educators.

There’s a bracing aura of self-possession about him, combined with an almost feline sense of mental and phsyical grace. “Dapper” is the word that comes to mind and one feels certain that Marsalis not only would win almost any game he tried to play but also look good while doing it. Jazz musicians, after all, used to be pace and style-setters in all areas of life, not just in music; and everything Marsalis says and does lets you know that he knows that.

But what makes him such an intriguing figure – aside from the sheer quality of his music – is that this young virtuoso also knows he has arrived rather late the day as far as the development of jazz is concerned.

His “so much stuff has been played already” remark touches on one of the problems: the fact that, for a young player today, the music’s heritage is both a treasure trove and a potentially overwhelming burden. But more than that there is Marsalis awareness that the relationship between jazz and the society that surrounds it is not what it should be.

“Everyone.” he explains, “has a need for acceptance. Now when you first come up like me, right now I couldn’t give a …. , if they don’t like my music, solid. “But as you get older and you’ve really contributed something, which I haven’t done yet, you look back down the road and start thinking, ‘Damn it’s been 10 years, and I’m still working the same gigs for the same amount of money.’

“And it’s not because somebody else is taking all the money. There’s no money there. You play in a club for three nights, and there’s 20 people there, and the cat who’s running the club has to pay the band $1,000 a night: you know that he’s losing money.

“So after all those years,” Marsalis continues, “this continual rejection breaks you down. That’s why in the ’70s a lot of the cats who could really play tried to make money instead. They were so tired of being treated secondhand that they just gave up. Jazz is the unique American music, and the country just doesn’t accept it. That’s the way it has been and the way it’s going to be.

“You’re in a no-win situation if you’re a jazz musician. For one thing, the black people don’t support you. Black people won’t pay a dime to hear a jazz musician play, except for older cats who remember Charlie Parker and people like that.

“But black people just aren’t being educated about jazz. And nobody is trying to make sure that it’s done and done right. Friend of mine in New Orleans told me when I came home from a tour with Herbie: ‘Damn, brother, you gettin’ up there. You playing with Herbie. Pretty soon you be playing with Earth, Wind.’ All I could say was ‘Yeah.’

Now there’s no reason jazz musicians should be making as much money as pop musicians because they don’t generate that kind of revenue. Jazz is a music that makes you feel and think, which is why we’ll never have a large audience. But the audience should be larger than it is.

“I go to hear the New York Philharmonic and I look at the audience and know that 60 percent of the people don’t know what’s happening. But the thing is, the society has told them that this is worth going to. That’s the way it should be with jazz.”

A long, rather stern list of grievances. And even though it may sound like Marsalis is stomping on sour grapes, anyone who has been around jazz for a while knows that just about everything he says is the gospel truth.

But if all that is so, why is this extravagantly gifted instrumentalist devoting his life to a music that virtually guarantees he will be treated as a second-class citizen, both financially and artistically, when he could quite easily hold down a chair in a symphony orchestra or make a comfortable living as session man in the commercial recording studios?

Sheer love of jazz would be one answer, and listening to Marsalis scat-sing entire Clifford Brown or Wayne Shorter solos to illustrate a musical point, one doesn’t doubt the depth of his devotion.

Equally important, though, and related to that love, is the fact that Marsalis needs jazz. It’s nothing less than his primary way of defining and expressing who he is as a human being-just as it was for Louis Armstrong, Bix Beiderbecke, Lester Young, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and host of other jazz artists who could no more imagine not playing the music than they could imagine not breathing.

“There’s a certain attitude that goes with playing jazz.” Marsalis explains, “that a lot of people today don’t understand, basic stuff that you just naturally know. Not stuff about music, stuff about life.

I’ll give you a prime example. I’m on a gig with Art Blakey and I play a ballad. So when I get finished, he walks up to the microphone and with all these people in the audience he looks over to me and says, ‘Learn the words to the tune, [expletive].’

“Now that didn’t make me mad and I wasn’t embarrassed. He’d told me something I needed to know in a way I would never forget. It’s like Art said to me another time: ‘Look, if you’re on the gig, play. If you ain’t going to play, get off the stand. That’s the bottom line on it, the gig. It’s a certain attitude about life, about being spontaneously alive – like ribbing or playing the Dozens [an elaborate game of verbal one-upsmanship]

I’ve talked to young trumpet players all over the world, and they ask me all the wrong questions. They want to take the music apart, break it down and analyze it. But there’s something that has to do with it that can’t be described.

“I know theory and harmony backwards, but how can you explain the way a cat like Dizzy Gillespie plays? I was giving a speech at a college the other day, explaining how technique gets in my way, and this guy said, ‘Well, Dizzy Gillespie has a lot of technique’. And I said: Yeah, but that’s his technique. It’s not a technique that Dizzy Gillespie brings in from the outside: What he plays is exactly that. what he plays. So it doesn’t sound like technique. It sounds like Dizzy Gillespie nailing Dizzy’s stuff.” ‘

Listening to Marsalis first album for the CBS label, on which he is joined by his very talented older brother, saxophonist Branford Marsalis, one has the feeling that he is very close to the point where it will possible to ignore all his remarkable technique and say instead: “That’s Wynton Marsalis nailing his stuff.”

He certainly wants to get there, and there’s every indication that knows how to get there, too. As he says. “What I can’t pick up intuitively, I’m going to sit down and figure out, just pick up that trumpet and gorilla some music out of it.

“That’s the thing about jazz,” he continues. “Can you do it? It’s like when we grew up and played basketball every day. Before you played you’d go, ‘I’m gonna kick your …’ and blah, blah, blah. You’re betting a dollar a basket, right?

“But eventually you know that all that is going to cease and you’ll have to get out on the court and pick that ball up. Then if you lose, you shut up, and if you win, you can talk all you want.

“Well, that’s how it is on the stand. “It’s not like we’re competing with each other; we’re making music. But we know when we’ve won and lost.

Believe me, we know.”

by Larry Kart

Source: Chicago Tribune