A family of music phenoms

It would require a long journey back into musical history to find a sibling team as precociously talented as the Marsalis Brothers. A couple of years ago they were just a pair of teen-agers unknown outside their New Orleans home, presently they have the hottest and most widely publicized new combo in jazz, a CBS Records contract, and a schedule that takes in festivals around the United States and Europe.

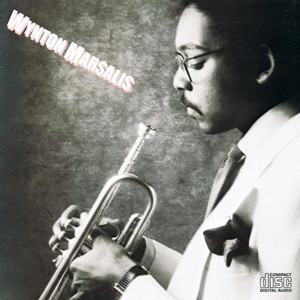

They are Branford Marsalis, born Aug. 26, 1960, and Wynton Marsalis, born Oct. 18, 1961. Wynton has been garnering 99% of the kudos on the strength of his astonishingly mature trumpet playing and his brash provocatively outspoken personality, but Branford, the saxophonist, is a soloist to be reckoned with.

Branford’s much more talented than I am,” said Wynton. “Until I was 12, I wasn’t going to be a musician, but he always was”.

Piano was my first instrument” said Branford. “Like father, like son.” (Ellis Marsalis, a respected pianist and teacher, plays with his sons on the recent album “Fathers and Sons.”) “Then I took up clarinet, but I realized I didn’t like it. I didn’t want to sit in a chair for the res my life playing music that was already written for me. So I had my dad get me a saxophone for Christmas.

Wynton, less reluctant to sit reading classical music, made rapid though belated headway. At age 6, he had been given a trumpet by Al Hirt, in whose band his father was playing, but, it remained in its case for six years while he concentrated on academics and basket ball. Once determined to follow his brother, he decided no less firmly that he would not be categorized.

He practiced relentlessly, but said, “I resent these stories that call me ‘classically trained’. Training is training: You practice scales and exercises and control and you use this experience to play anything you want.”

At 14, he played the Haydn Trumpet Concerto with the New Orleans Philharmonic. “Wynton got better and better.” said Branford, “because contrary to popular belief, music is about besting. There was this other kid David, in high school, who played a lot of trumpet, and Wynton just said, ‘Man, I’m gonna practice until I zip this kid.’ Musical envy, shall we call it?

“As for me, in high school I listened to funk for a long time – people like King Curtis – but later I began paying attention to jazz: Charlie Parker, Cannonball Adderley and then when I went on the road with Clark Terry’s band, someone told me about Wayne Shorter. In four months I learned every solo off every album Wayne had done with Miles. John Coltrane was a very recent discovery for me.”

Wynton left for New York in the summer of 1979, a few months before his 18th birthday. In addition to studying at Juilliard, he played in a pit band and worked with the Brooklyn Philharmonia. Then one day I sat in with Art Blakey, who’s a master of Afro-American mu sic. Blakey asked me to join his band, and that was a truly educational experience.”

Last year Wynton left Blakey, toured Japan and the United States with a quartet that included of Miles Davis’ 1960s rhythm section (Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams), then formed his own quintet, with Branford playing tenor and soprano sax.

While soaking up this all-embracing span of musical knowledge, Wynton acquired a set of strong social and racial views, most of which seem to be shared, though less vigorously expressed, by his brother. His opinions bring together into intriguing juxtaposition the certitude of youth and the maturity of middle age.

“Some people think that my telling the truth means not liking white people, or being arrogant. When you grow up you don’t hate anybody: You have to be taught that, man. Even right now I don’t hate anybody.”

According to his experience, whites have a tendency to be defensive about white musicians. “At one interview I talked about Louis Armstrong and the interview er immediately brought up Bix Beiderbecke. Now I’ve listened to both of them, and Bix was a great player, but Louis was a genius of the first level.

“I can say I don’t like what Anthony Braxton plays, and he’s blacker than that chair – but I can’t say I don’t like a white boy. If I don’t like Richie Cole, I must be a racist.

Wynton Marsalis represents a more substantial way of thinking than most whites may be willing to realize. After high school he had a chance to go to college; as a national merit finalist he had approaches from Yale and other Ivy League schools, but was reluctant, he says, to be in that environment.

“I had been going to white schools for a long time The education is better, but the problem is the racial vibes you have to deal with. I had all A’s, and the white cats would be so upset.

The Marsalis brothers grew up in a superior family environment (“We had a father – we were ahead of most black cats right there”). There are now six brothers: the others are 17, 16, 11, and 5. Ellis Marsalis, to whom his sons were always close, encouraged them in their ambitions. It may be a fair assumption that without his jazz background their own musical experience would have been very different.

Both Branford and Wynton became aware early that their exposure to jazz was not typical of black experience in the 1960s and “70s. Among other roadblocks they found that jazz was taboo in black colleges.

“They refuse to accept anything that hasn’t been set down in the rule books for centuries,” said Branford. “If they found you playing jazz in the practice room, they’d come in and say, ‘The rooms are designed for serious musicians.’ Gospel music, which is the core of black music, is frowned upon too. European music is all they allow. Our integrity as black people has been destroyed.

Wynton Marsalis elaborated: “I hate to say this, but black people have spent their time in this country trying to refute their culture. Slavery created an inferiority complex in them. The black church, which is primarily a black version of a white institution, also helped to cut jazz down. The churches don’t want to hear about jazz. Being the great influence they are on black people, that means you’ve lost 70% of the people right there.

“If black people want to listen to funk or soul music rather than jazz, that’s for social reasons – it has to do with not being educated for four centuries and dealing with complexes that are forced on us by society. I played in a funk band, and if we’d try to play a good jazz tune like Herbie Hancock’s ‘Maiden Voyage,’ people would say, ‘Hey, what’s wrong with you? Play us some music – we want to dance.

“Stop any black person on the street and ask him who’s the most profound black artist, who’s the genius. Who do you think they would say? Stevie, that’s who. Now I think Stevie Wonder is great, but for him to be set up as the sublime artist while Sonny Rollins and Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock – or Thelonious Monk, who just died – for those people to be ignored is a shame.

“Branford added what he sees as the basis of many difficulties in interracial understanding: “As a black person, you will always be accepted by whites as long as you identify with that which is natural to white culture The minute you begin to exemplify anything that is black, it changes. I don’t think people’s attitudes are going to change in our lifetime.”

Easy though it is to emphathize with the brothers’ skepticism, indications seem to be growing that conditions may improve in the foreseeable future. The best evidence, in fact, is provided by the Marsalis phenomenon itself.

Wynton Marsalis is the first musician, black or white, playing non-fusion, uncompromising acoustic jazz, to become the object of a high-powered promotional campaign launched by a major record company. He has been playing with incredible success to predominantly white listeners, who evidently are able and willing to relate to this aspect of black culture.

Unprecedented, too, is the stipulation in the Marsalis CBS contract calling for him to record a classical album. Never before has any jazz musician been signed under these conditions. He will fulfill this part of his obligation next December when, in an album to be recorded with the Czech Philharmonic in Prague, he will play the Johann Hummel Concerto for Trumpet and Henri Tomasi’s Concerto for Trumpet and Orchestra.

Still another notable aspect of the New Orleans youngsters’ accomplishments is their insistence on a dignified appearance. “People relate to what they see, said Wynton. “You can’t come on stage looking like you’re dressed for a football game. We believe in protocol, punctuality, a visually smart presentation.” To see the Marsalis brothers in their carefully selected suits, shirts and ties is to be reminded of a tradition that was all but lost in the generation of jeans and dirty, torn jackets.

With the help of these young, dedicated and immensely gifted artists, who transcend the barriers between classical music and other idioms, an attempt is being made to erase a series of anti-jazz stereotypes and prejudices that has lasted almost a century. The Marsalises have the right ideas at the right time, and they didn’t arrive a moment too soon.

By Leonard Feather

Source: Los Angeles Times