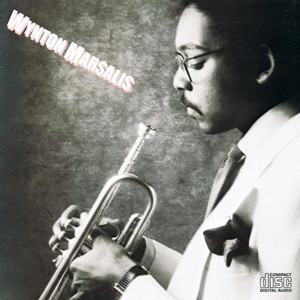

Profile: Wynton Marsalis (Downbeat 1982)

When Wynton Marsalis was six years old, his father, Ellis Marsalis, was playing in Al Hirt’s band. At that time, Hirt gave young Wynton a horn. Fourteen years later, Wynton has completed one jazz album, plans to record a classical album, is a full scholarship student at Juilliard, and the winner of the 1981 down beat Critics Poll for talent deserving wider recognition in the trumpet category. Never let it be said that Al Hirt doesn’t know potential when he sees it.

Marsalis’ serious approach towards music began when he was in high school where, with the help of several eager teachers, he was playing the classics by the time he was a sophomore. His work at the Eastern Music Festival in North Carolina earned him the “Most Outstanding Musician Award” there in 1977. The next year, he purchased a piccolo trumpet and performed Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 with the New Orleans Symphony Orchestra. He spent the summer after his high school graduation at Tanglewood (MA), playing under the great classical conductors there.

After entering Juilliard, Marsalis also performed with the Brooklyn Philharmonic and was a soloist with the Mexico City Symphony. Since coming to New York in 1979, he has also done Broadway work, putting in some time in the pit band of the musical Sweeney Todd. He took a leave of absence from Juilliard to perform with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, and when he first played New York with the group, music writers there were suitably impressed. A six-week festival and concert tour with the Herbie Hancock Quartet followed during the summer of 1981, and by September Marsalis had his first record for Columbia in the can.

For a 20-year-old given a start like that, Marsalis could probably let success go to his head. He says don’t count on it. Marsalis feels his seriousness about music and his drive to combine those elements in jazz that he thinks are important — “spontaneity, melodic ideas, sounds” — coupled with a deep belief in the validity of jazz as a serious music will keep him working at developing his talents. His reasons for playing are simply stated: “I love playing the trumpet. I love playing music. I love playing jazz. I want to play … to let people know that jazz is just as valid as any other music.” In place of the phrase “any other music,” read the word “classical,” something with which Marsalis is very familiar. One of the main reasons for his returning to Juilliard is to explode a few myths about jazz musicians not being able to play classical and “to get the degree for all the cats who don’t think brothers can do it.”

One could make a good argument about Marsalis’ musical seriousness coming from his father, pianist Ellis Marsalis. Indeed, Wynton makes no secret that talent runs in his family. His brother, Bradford, has played saxophone with Art Blakey, and another brother, Jason, is a budding drummer, whom Wynton says has perfect pitch and is going to be “the baddest of them all. It really wasn’t my family, though. My father’s presence helped me tremendously, but we weren’t a musical family. That wasn’t the basis of my family life.” The advantage Marsalis had, he says, was that “I could always go on jobs and hear my father play, and the records were always available to me.”

Thal trumpet Al Hirt gave him at six was not used much until Marsalis hit high school, where there were a lot of other good trumpet players and “the competition was a lot greater.” At that point he also began listening to Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Louis Armstrong, Fats Navarro, and Clifford Brown. His interest In playing Jazz was spurred “especially when I first heard Clifford … I didn’t know someone could play a trumpet like that. It was unbelievable.” Consequently, he began taking lessons from John Longo, who is now playing in the Mercer Ellington stage band in Sophisticated Ladies on Broadway.

Though his classical finishing school may be Juilliard, his jazz finishing school is the road. For the spring and summer semesters of 1981, his instructors were Art Blakey, Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, and Ron Carter. What did they teach him? To put it simply, “everything. I learned a lot of stuff from him [Blakey], but it’s not the kind of stuff you learn in school. Art Blakey never told me what scale to play … he’d tell me stories about Clifford. I didn’t learn anything technical about the trumpet. I learned about playing music.” As for Hancock, Carter, and Williams, “There’s nothing I can say about them. They’re the greatest in the world, period. Herbie Hancock has ears. He can hear. He, Ron, and Tony function as one unit … you know what that’s like? They understand the history of their instruments — the jazz history and the guys who played before them.”

Part of that jazz history, to Marsalis, is the belief that jazz comes from the black American cultural heritage, which is not something you can find in a $12.98 fake book. “It’s not taking a ‘Ihme solo and analyzing the notes be plays on the chords, because that’s insignificant. It’s not saying, ‘Oh, all Bird was doing was ii-V7-I’s, and sometimes he would juxtapose the augmented fourth on top of it.’ That’s bullshit. That’s not what Bird was doing. Bird was making a very personal musical statement. And it came out of a certain historical movement. That’s why I’m saying this is artistic music.

“American people have been taught history in a distorted way. You say Beethoven to most people — [even] if they don’t know music — and a certain image is projected in their minds. You say Charlie Parker, (and] the image that is projected in their minds is, ‘Oh, he was that junkie.’ The music stems out of our suffering in this country — it’s our statement — and we as a people don’t accept it. Most of the audiences we play for are white, because they recognize the music as a significant contribution to Western culture and civilization.”

Marsalis believes it is the conscious recognition in the minds of most white jazz players that they are not black that limits their ability and prevents them from getting “into the meat of the music. There’s no way I could compose music — German music — like Beethoven did. It has nothing to do with the color of their skin. It’s the fact that they say, ‘Oh, I’m white,’ and they start trying to act black. Any white guy who tries to act black will never be a jazz musician. He can forget it. Just like a black guy, trying to act white, being a classical musician. Everybody can play any kind of music,” he says, trying to clarify his statements, but the only way you can do anything is if you understand the concept.”

While being critical of white copyists who slavishly repeat Coltrane licks without understanding the feelings behind them, Marsalis is also critical of blacks, whom be says do not give the music the recognition it deserves. Don’t expect to hear Marsalis playing funk, which be calls pleasant “entertainment” music. He’s too busy trying to develop bis jazz chops to the degree that Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, Freddie Hubbard, Miles, and the various others he names as his influences have develeloped theirs.

“I do not entertain and I will not entertain, I’m a musician. I studied the music and my music should be presented that way. I’m serious about what I’m doing. I will not play funk. I like funk, but I am not a funk musician. Funk musicians don’t pay the kind of dues that jazz musicians pay to the music.” His recording debut on Columbia, he states proudly, will be a jazz album. It will feature his brother Bradford, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Tony Williams, and others. “I took the route the record company doesn’t think is commercially viable.” he says of the album. “But record companies aren’t musicians, they’re great businessmen. I don’t tell them how to run a record company. They don’t tell me how to play music. If Herbie wants to play funk, if Miles wants to play funk, if Freddie wants to play funk, or whoever is playing funk — I think it’s beautiful. But the worst thing is when the record company takes a funk album, puts it out, and calls it a jazz album.”

Marsalis soon plans to release a classical album as well. But he still approaches jazz with a healthy respect tor those who came before him — people like Wayne Shorter, Lester Bowie, Barry Harris, Clifford Jordan, Sonny Rollins, Duke Ellington, and others — and a wary eye on record companies and his own playing ability. “I can play the trumpet well. My ability to play the instrument is good. So far as being a jazz musician, I have a lot to learn. My playing isn’t spontaneous enough. I play too many eighth notes. It’s not open enough. I have a lot to learn … we all have a lot to learn.

Even Thane was looking for stuff until the day he died. “

“I’m doing what I want to do: I’m playing jazz, period. And if I get squashed — there’s always that possibility — I get squashed. But I’m functioning on the premise that this is good music and it deserves to be heard. And I am a jazz musician … my father was a jazz musician. I play jazz.”

by Mitchell Seidel

Source: Downbeat (January 1982)