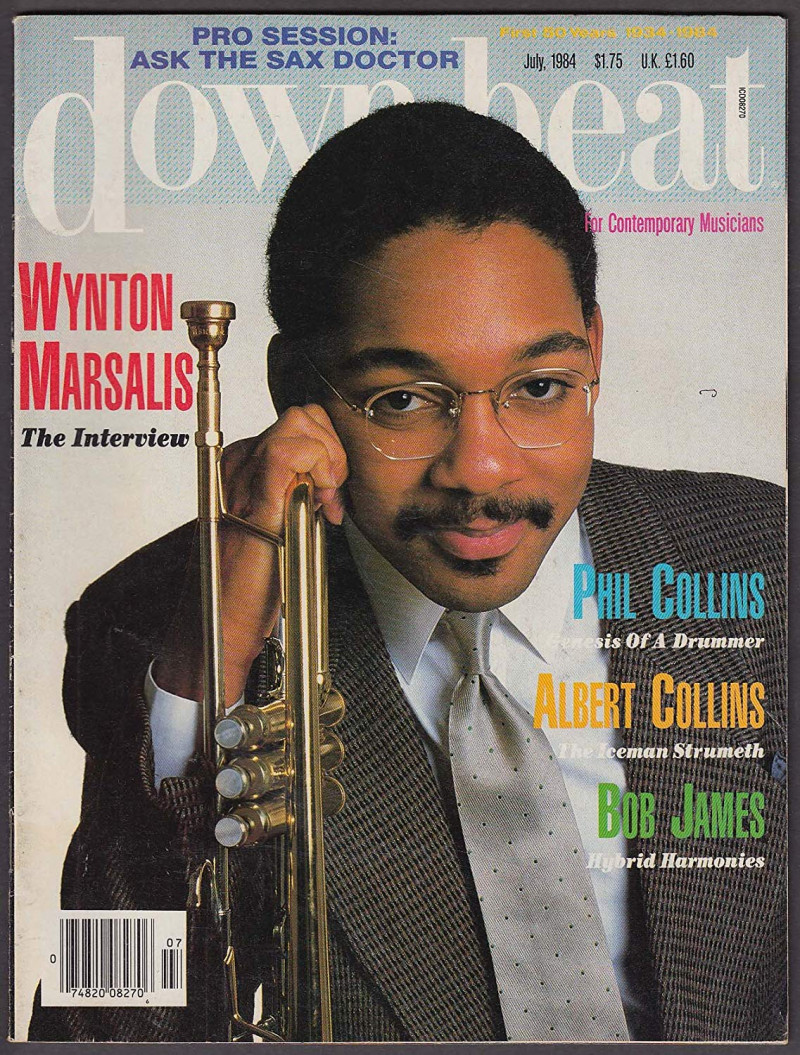

The Wynton Marsalis Interview

Downbeat (July 1984)

Wynton Marsalis is still the wunderkind, a 22-year-old son of the Crescent City, bowing to accolades from the jazz world with a trumpet in his hands, nodding towards the European classical tradition with equally serious vision. After becoming the first musician ever to win Grammys in both jazz and classical categories – with uncompromisingly traditional productions yet! – Marsalis sauntered into CBS headquarters in Manhattan one late morning, after a day of travel from New Orleans to New York, to Philadelphia for a classical recital rehearsal, then back to his brownstone (shared with his brother, saxophonist Branford) in Brooklyn. He had scheduled, in the near future, a concert with the Boston Pops, but was eschewing a summer tour of European jazz fests to mount a trip through the U.S. and to Japan with his quintet (as of this writing, Branford on tenor, pianist Kenny Kirkland, bassist Charles Fambrough, and drummer Jeff Watts).

It took a few minutes for the opinionated, good humored, and very personable young man to warm up. What he needed most was breakfast, and when he got it, ideas began pouring forth as solos shoot from his horn: confidently brash, improvised from a well-considered and consistent viewpoint, whole. What follows is an edited tran-script of our discussion.

Howard Mandel: I was wondering about your early playing experiences in New Orleans. I’ve read your bio …

Wynton Marsalis: A lot of that stuff is incorrect, though.

HM: What’s the truth?

WM: Let’s see, this is difficult. Well, you know my father’s a musician. So I had a trumpet when I was six. I wasn’t really serious about music, but when I was eight or nine I played in the Fairview Baptist Church marching band, led by Danny Barker, for young kids like us. But I was the saddest one in the band. We played at the first New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, but I remember I didn’t want to carry my trumpet because it was too heavy, so after an hour somebody else was carrying it for me.

So we grew up. My father was always working gigs, trying to make enough money to feed all of us, because New Orleans is rough on jazz musicians – there’s really not that many gigs there. He worked on and off in different places, free-lance, then he started teaching at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts. At that time I was 12; I had a trumpet but didn’t really play. I knew tunes like The Saints and second line, but I didn’t have any technique. I just heard music.

HM: In a previous interview, you said playing together wasn’t part of your family life.

WM: My father was working all the time at night, and we were going to school during the daytime. But one thing I remember: once I got serious about music, the best thing about New Orleans for me and other young musicians is that we had a generation of older musicians, maybe seven or eight people, who loved music so much they would do anything for us, because we were trying to actually play it.

My father would stay tip with anybody – not just me, ‘cause I’m his son – but any musician could come to our house after 11 at night, and my father, if he was home, Would show them tunes, play changes and all. Get these names, they’re important: there was my father; [clarinetist] Alvin Batiste; John Longo, my first teacher – I hardly ever even paid him, and he used to give me two-and three-hour lessons, never looking at the clock; Clyde Kerr; Alvin Thomas – he died; Kidd Jordan, who put on a concert that brought together the World Saxophone Quartet – I was there, but I didn’t know any music but pop music then; George Jensen was my teacher – he just died, too; Danny Barker, who led the band. All these guys wanted us to learn how to play.

HM: Did they steer you away from playing junk?

WM: No, as a matter of fact, my father told me to go play in the funk band we had when we were in eighth grade. He said, “Man, go play in the band, get some experience at playing music.” I’ve told this to people in interviews, but they always write the same thing, using me to express what they want to express. I’ve never said popular music is not good. All I said was it’s not jazz. Thats just clarification for purposes of education.

Man, I played in a funk band for four years; I know all those tunes from the ’70s, by Earth, Wind & Fire, Parliament/Funkadelic. I played that music. That’s why I know it’s not jazz. People think a simple statement like that is condescending to some other kind of music. But all music is better than no music.

HM: But you have a good idea of what you want todo yourself, and it’s in the jazz vein …

WM: What I’m saying is I’m a student of music. I’m humbled by music, not by people. Great music is what humbles musicians, and it’s the precedents set in music that keep musicians honest. When you start redefining what music is, and replacing something that’s great with something that’s mediocre; then the next generation of musicians doesn’t know what their job is. I’m embarrassed to admit it, but when I joined Art Blakey’s band, I hadn’t even listened to Art Blakey’s records. I was just playing scales on chords – I didn’t know you were supposed to construct a solo.

HM: You must have studied assiduously from Blakey on, because your music seems closely linked to the jazz of the time you were growing up.

WM: People miss a great part of what my music has. They don’t understand what we’re trying to do, but they think they do, and they lash out against it. I have to phrase this very delicately. My music is a very intellectual thing – we all know this – art music, on the level we’re attempting. Sonny Rollins, Miles, Clifford Brown, Charlie Parker – we don’t have to name all the people, maybe just the main ones – Monk, Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong. These were extremely, extremely intellectual men. Whoever doesn’t realize that is obviously hot a student of their music, because their intellect comes out in that music. It’s obvious that the average person couldn’t stand up and play like that.

See, the faculty of creating comes with observation, hand in hand. The ability to translate what is observed into a very precise language, that’s where the intellect comes in. People have every kind of tragedy imaginable befall them – that doesn’t make them able to translate their experiences into as precise a language as music, ‘cause they don’t have the technique to do it. They might have the imagination, but they don’t have the invention – because invention means worked out.

But in jazz, people write it backwards. They think the opposite way, most jazz critics. They think because Louis Armstrong sat back all folksy, that in his mind he didn’t know. How many times have you heard, “Louis Armstrong was an intuitive genius”? That implies he didn’t know he was great, he just naturally could do that. It implies that he was just lucky. But if you’re lucky, you can’t be consistent. Pops was not an intuitive genius; he knew what he was doing, and I’ve read interviews he gave where he let people know that he knew what he was doing.

HM: But Armstrong, Ellington, all the great artists, had spiritual and emotional resources too, not just intellect, didn’t they?

WM: You never find a musician with technique as great as theirs who doesn’t have the other two. Never. People get confused, and think velocity is technique. It’s not. Emotion is an aspect of technique. If your intellect is on a certain level, like Ellington’s was, you automatically experience those other things. We think of intellect as sitting down, reading, and spewing out the words we read. Then there’s somebody who has the sensitivity to observe what’s around them, process it, and make something out of it. Someone has intellect who knows what their relationship is to what goes on around them; great artists always have that. That’s the key to any music. And that’s what makes them have the technique – because they want to be great, and they understand they aren’t great, so they develop the technique to be great. You have to defer to the musicians who keep you honest, like Beethoven writing in his letters, “Don’t compare me to Mozart and Haydn, yet.” Bird spoke of Lester Young; Pops talked about King Oliver; Duke Ellington deferred, too. Duke had everything, but that’s because he experienced life on a more acute level than most of us do, because he was so aware of what was going on around him. That’s what’s important.

Jazz is about elevation and improvement. Jazz music always improves pop music. What Louis Armstrong did, singing songs by Gershwin and Irving Berlin, was improve them. Bird improved I’ll Remember April, just like Beethoven improved folk melodies. What we have to do now is reclaim, because the cats went astray in the ’70s.

HM: On reclaiming music: I take it you’re reacting to music watered down by fusion, simplified by funk. You think there’s nothing there.

WM: Everybody knows it, too.

HM: But rather than reclaiming, you’re exploring things from the ’60s.

WM: People don’t hear what we’re doing on Think Of One. I’m doing things from the ’70s, too, because that’s the era I grew up in. I had all the records, man. We’re playing funk beats, too. We don’t reclaim music from the ’60s; music is a continuous thing. We’re just trying to play what we hear as the logical extension. But before you understand what the extension of something is, you have to understand what that something is. If you don’t study and understand it, a large part of your pro-gram’s missing – to me, the most important part. A tree’s got to have roots.

In the ’70s the tunes were static. They aren’t like Monk’s tunes, man. The goal of the music was different; a different element was introduced, arid if it’s good, and popular, well, good for that. But the musicians know that what Trane and Mingus, Monk and Miles did in the ’60s was the baddest stuff. Duke Ellington’s bad, man. That’s the level the music must exist on.

HM: What got established in the ’70s, within the jazz tradition, that moved the music along?

WM: Nothing. Not one thing. I don’t think the music moved along in the ’70s. I think it went astray. Everybody was trying to be pop stars, and imitated people who were supposed to be imitating them. Then there’s the school of music that sounds like European music people were writing in the ’30s.

HM: You’re very interested in European music.

WM: I love European music, great European music Europeans wrote, ‘cause it’s great music. I like pop music too, but neither one is jazz.

HM: Are you particularly fond of the Baroque period?

WM: No, I love every period. I love Bartok. I put out one record, and played classical concerti, because on your first record you have to show people you know this part of the literature, because it’s standard. I love Bach, too. My new album has Baroque on it, too. My recital program includes some modern music by Hindemith and Halsey Stevens, which is Copland-sounding. I played a Hale Smith piece, Exchanges, when I was in school.

HM: When do we get to hear some of that?

WM: I’m 22 years old, man! I can’t record everything at once. Right now I’m just doing this; Baroque music is cool. All music’s the same, saying different things about human existence at the time. Pop music is here today, gone tomorrow. Great music is idealistic, but it’s realistic.

HM: Maybe pop music is trying to be great studio music?

WM: Ain’t nothing happening in pop music, today. In the ’70s you had Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, creative cats, geniuses, making music that musicians would try to sit down and figure out. Now in pop music they’re just trying to see who can wear the most sweaters, dresses, Jehri-Curl their hair. The arrangements behind Michael Jackson are nice arrangements, but Duke Ellington did arrangements in 1930. What standard are we using? Compared to what? Louis Armstrong made statements for all time about the condition of American humans at the time that he loved. To me, in music in the past five years, I don’t hear anything great.

HM: When you compose, are you trying to express a particular idea?

WM: No, an overall feeling. It’s difficult to translate music into language, because music is its own universe. You’re just trying to write or play music. And theres so much going on, especially in jazz. Because jazz is the most precise art form in this century.

HM: What does the precision attach itself to? Where can you hear it?

WM: The time. What the jazz musician has done is such a phenomenal feat of intellectual accomplishment that people don’t believe it is what it is. What the musicians have figured out is how to conceive, construct, refine, and deliver ideas as they come up, and present them in a logical fashion. What you’re doing is creating, editing, and all this as the music is going on. This is the first time this has ever happened in Western art. Painting is paint_ed_. Symphonies are writ_ten_. Beethoven improvised, but by himself, over a score. When five men get together to make up something, it’s a big difference.

HM: But when you create with your band, there’s a thoroughly understood idea of what’s going to happen in the piece.

WM: No. There’s a language of music present, but how that’s going to be used, how something will be used to achieve whatever effect you’re after, we don’t know what that is. First thing is, we don’t have set chords all the time. We don’t play on modes, ever. Whatever chord Kenny plays, that’s what chord it is. If Jeff plays a certain beat, the piece becomes in that time. The form has to stay the same, the structure must be kept, but our understandings are very loose. We understand the logic of our language.

I love my band. Kenny Kirkland and Jeff Watts are the greatest young musicians on the scene, and they get no credit. People say Kenny can’t do this, and Jeff can’t do this, but they don’t hear what they are doing, because they’re too busy hearing what they’ve already heard. Then they say it sounds derivative. What you have to do is not look at part of something and make that into the whole. When you hear my records, I want you to listen to the sound of each piece, the flow of it, just like you would with any music. I listen to the sound of music, then the textural changes. Then I think, what are they trying to say in this? And I figure out what’s going on, not theoretically, but musically.

When I study, I listen to certain things, specifically, for a reason. What’s on this record? What chord is this? How does he get to this chord? What’s the development section to this? What’s the drummer doing here? What chord does this affect? How do these two people hear this? How can you achieve this effect? I can listen to Schönberg and analyze those pieces, I’ve read Structural Functions Of Harmony, and I know what’s in that book – I’m not guessing; I know what he’s saying. I sat down for hours until I knew what was being said. But the theories now hurt me more than anything, because these people are not sincere, and they don’t want to pay the dues that it takes to learn how to play this music. They don’t swing at different tempos. What you must learn to play our music is not being learned-and cats are getting over.

The most important thing in jazz is swing. Rhythm. If it don’t swing, I don’t want to hear it; it’s not important to hear whatever it is if it’s not swinging if it’s jazz. There are different feelings of swing, but if it’s swinging, you know it. And if you ain’t swinging, you ain’t doing nothing. The whole band must swing. You can’t have weak links. Every musician in your band has to be as good as the others – has to hear just as well, understand the concept as well, think on ‘his feet just as well. See, our music is really for the moment – that’s what makes it so exciting. That’s why it can either be sad or great.

We’re just trying to come up with an improvisation on the spot. Bam! D over E♭. What is that? You know, immediately, what the chord is. You’re going to five, you know what the rhythm is, you just have to respond. But it has to be correct; it’s not just playing any kind of thing. You don’t just hit a chord ‘cause you feel like hitting it – you got to understand the logic of the progressions of harmonies – the logic of sound, the logic of drums, the logic of how bass parts should go. Contrary motion. That’s what my brother and Kenny Kirkland understand real well. On those records I didn’t write out any music for Bell Ringer and those long tunes. I just said, “Branford, play a contrary motion there. Kenny, what do you hear on top of that, man? Jeff, what rhythm do you think would fit there?” Good ears, man. Musicians.

HM: Do you yourself hear music your small ensemble isn’t capable of, just because of instrumentation?

WM: No, I don’t hear any. I only play for, and think about, that band. But we only play 30 to 40 percent of what we’re capable of, definitely. We’ll come off a gig, all depressed because the stuff sounds so sad, and we’ll say to ourselves, “Hey, we’re gonna get this.” We know what we have to do; it’s just a question of doing it. And we’re going to do it, because we want to, we want it bad. We practice and we play; we don’t just wait for the ability to play to descend on us; we’re going to learn how to play. Its a matter of time. Five, six, eight, 10 years, 15, who knows? We’ll get to it.

And this is what we need: younger musicians. Cats like Charnet Moffett, 16 years old, coming over to my house every day to learn about harmony on his bass, to learn about music. To the young people who read this, we need young musicians trying to really learn how to play the music and researching and learning how to play their instruments. Not all these little sort of pop-type cult figures, talking-all-the-time heroes who have these spur-of-the-moment, out-of-their-mind, left-bank, off-the-wall theories about music which make no sense at all to anybody who knows anything about music. We shouldn’t get rid of them – they’re important, because we know through them what bullshit is. But musical terms are very precise; these terms have histories to them.

HM: Do you feel a lot of pressure, as a guy who looks good, plays sharp, and studies, to represent the young musicians coming up now?

WM: No, there’s no pressure on me, ‘cause that’s how I am. When I was going to high school, I never owned one suit. I didn’t know what it was to spend money. I went to school with the same pair of jeans on every day, a t-shirt and shirt from Sears on top of that. Alright? Now, when I come on, I do what I want to. I like to be clean, because I used to look at album covers of cats with suits on, and I’d say “Damn, look at that suit; boy, let me get one; I wish I had a suit.” I like suits; I like to be dean when I go to work, playing music that I think is important in front of people.

Now, the underlying thing is I love the music. See, I’m not out here trying to garner publicity – I’ve got publicity, right? I don’t call people asking them to interview me. I didn’t call CBS and ask them for a record contract. Just for some reason, I started playing with Art Blakey, then the next thing I know· I got a record contract; everybody’s writing reviews on my stuff; I’m playing with Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter and Tony Williams – it happened just like that. I was still trying to learn how to play the music. I didn’t come to New York to be a jazz musician. I didn’t even know people were still playing jazz. I grew up in the ’70s; there wasn’t any jazz in the ’70s. Now I’m being like I want to be.

HM: Was winning two Grammys this year your biggest honor yet?

WM: No. The biggest honor I ever had is for me to play with the musicians I’ve played with. To stand on-stage with Ron and Herbie and Tony, Sonny Rollins, Dizzy Gillespie, to have the opportunity to talk with them and have them teach me stuff.

I’m playing jazz because I want to play the music. I love this music, man. I stay up all night playing music. Now, you can say what you want to say; I’ve got such strong opinions because I love the music, and I hate to see bullshit put up as the real thing. Thats the only reason; not because I want people to think I’m it. I know I’m not Louis Armstrong; I’m not fooling myself When I hear jazz, great jazz, there’s no other feeling like that for me. None. Beyond all the other stuff, the publicity and the hype will be gone eventually, but the music will still be there, and I’m going to still be playing it if I’m still alive – or trying to learn how to play it, because I realize how great the music is, and that’s what’s most important.

by Howard Mandel

Source: Downbeat