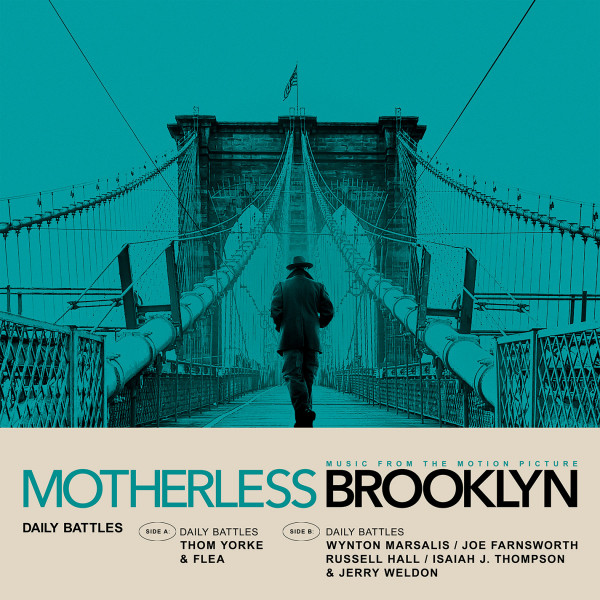

Why Edward Norton Tapped Thom Yorke and Wynton Marsalis for His New Movie, Motherless Brooklyn

In his new adaptation of Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn, Edward Norton plays Lionel Essrog, an orphan detective with Tourette’s syndrome, who wanders the streets of New York attempting to solve the murder of his mentor and father figure. Norton, also the film’s director and screenwriter, changed a few key elements of Lethem’s novel, transplanting the neo-noir from its original setting in the late ’90s to the 1950s. But something Norton did not lose was its singular fascination with music and pop culture.

In the book, Lionel takes a moment from the byzantine workings of the central murder mystery to remember the first time he heard “Kiss” by Prince: “It so pulsed with Tourettic energies that I could surrender to its tormented squeaky beat and let my syndrome live outside my brain for once, live in the air instead… When I listened to him I was exempt from my symptoms.” The Prince passage took up only a page or two, but it was Lethem’s first overt dabbling with characters who lovingly over-identify with a piece of pop culture—his next several books would be brimming with music, movies, and characters who were hopelessly entangled with both. “That was the beginning of me having characters who care inordinately, who care almost dangerously, about popular music,” Lethem tells me.

Throughout the film, Lionel still finds liberation in music, but this time, it’s the era-appropriate hard-bop jazz of a Harlem nightclub. “Jazz is a great analogy for Lionel’s head,” Norton says over the phone. “Hard bop, in particular, is all Tourettic, in the best sense. It’s everything I love about Charlie Parker or Mingus—this anarchistic, improvisational approach to music.”

Norton acquired the rights to Motherless Brooklyn before it was even published in 1999. With Lethem’s blessing, he air-lifted the characters from their original setting and deposited them into a sort of noir-film fantasia version of 1950s New York City. It comes complete with its own thinly veiled version of Robert Moses, the famed urban developer and old-world political boss, who is played with Trumpian relish by Alec Baldwin. Norton’s change is audacious: “Setting it in the ’50s opened the door into a deeper narrative about the social history of New York.”

The changes did not bother Lethem, though he does note one thing with a laugh: “I had my own vision of what Lionel looked like—and he was closer, at the time, to Brendan Fraser. So when Ed expressed interest, I remember thinking, ‘Well, you’re very famous and important, but that’s not right!’” Remarkably, the author never read any version of the script and had only seen the film once when we spoke. “I don’t take a lot of pleasure in the kinds of movies that result when people are slavishly obedient to a book,” Lethem says. “What I wanted is what [director] Howard Hawks did with Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not: Keep the title, keep the boat, and then make a really good Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart movie.”

When it came time to soundtrack and score the film, Norton turned to what he called a “team of three authentic geniuses” to help him realize his vision. First, he sent the script to Thom Yorke. “I’ve always felt like, as a writer, Thom understands fracture and dissonance, but his songs also have this emotional longing,” Norton says. “He’s also written a lot about how the world and the powers that be are oppressive. To me, Lionel’s head sounds more like Thom’s longing than like hard-bop chaos. I had this middle-of-the-night idea to ask Thom to write a ballad that felt like it was out of the past, something like the Chinatown theme. Ten days later, he sent it back to me.”

Yorke’s contribution to the soundtrack, “Daily Battles,” is a mournful piano ballad featuring smoky trumpet-playing from Flea; it would not seem out of place on Radiohead’s 2016 album, A Moon Shaped Pool. “I was intimidated but intrigued by Ed’s idea of trying to write a song that felt timeless, from a different era,” Yorke tells me via email. “[Like] a lost musical standard that could fall seamlessly into the hands of a small, Kind of Blue Miles Davis jazz ensemble, but at the same time still be me, and still be modern. When I read the script I kept returning to this idea of ‘the other side, it has no face.’ Do we allow the powerful to walk all over us, or do we wake up, go after these people, and take them down?”

The song made such an impact on Norton’s understanding of his own film that he ended up burying some of Yorke’s lyrics into the script, as Easter eggs: “We all have our daily battles,” remarks one character. At another point, Lionel refers to his condition as needing to have “everything in its right place.” And there is even a sneaky, almost-quote of the Radiohead song “Like Spinning Plates” that pops up in a pivotal scene, with its instantly recognizable backwards tape reel sound effect.

Authentic genius number two was trumpet virtuoso Wynton Marsalis, who arranged a cool-jazz version of “Daily Battles” for a slow-dance scene and helped to establish period authenticity for a club scene. “Norton told me the music was a combination of Miles Davis and [trumpet player] Clifford Brown,” Marsalis says. In the film, the actor Michael K. Williams mimes the trumpet, but Marsalis is the one playing. As a rowdy Clifford Brown number heats up, Norton’s Lionel—unable to help himself—starts scatting along. “I love the way he played it,” Marsalis adds. “When he started to imitate the music, I thought some of that would come off corny, but he pulled it off.”

Composer Daniel Pemberton, genius number three, took about a month to write the film’s sprawling score, full of ambient synthesizers, jazz-inflected saxophone bursts, and rich string writing. The night Pemberton and Norton met, the former had finished scoring Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse just hours before. The two bonded over Vangelis’ music for the historical sports drama Chariots of Fire, from 1981. “Usually directors mention the trendy scores of that year or the year before,” Pemberton says. “Chariots of Fire is not the ‘cool’ choice.” But Pemberton loves the score so much that he bought Vangelis’ CS80 synthesizer with the first money he ever made from scoring films.

Pemberton tracked the Motherless Brooklyn score in just three days at Abbey Road Studios in London. When Marsalis and Pemberton finally met, the jazz great looked up at the composer and paid him what Norton now calls the highest compliment imaginable: “You wrote all this in the last four weeks?” Marsalis asked. “You are a bad motherfucker.”

by Jayson Greene

Source: Pitchfork