The short and the long of the American conversation in Wynton Marsalis’ Concerto in D at the Bowl

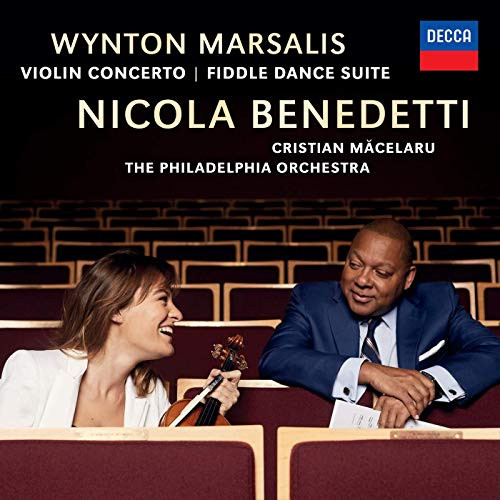

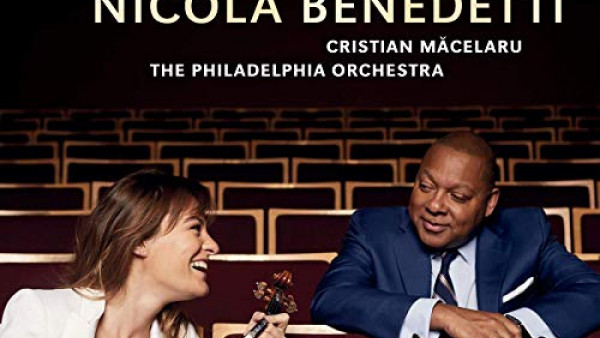

Violinist Nicola Benedetti performs the West Coast premiere of Wynton Marsalis’ Concerto in D, with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, conducted by Cristian Macelaru.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Every election year is about competing visions of America and what it means to be an American. Political parties this summer are particularly divided between and among themselves. The Hollywood Bowl, however, has offered to help with the vision thing.

Last week the Los Angeles Philharmonic offered three essential examples of American musical hybridization, often with political overtones. The examples began with guns, gang warfare and immigrants in Leonard Bernstein’s “West Side Story.” The symphonic excerpts from George Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” concerned race, and his “Rhapsody in Blue” proved a historic meeting ground for jazz and classical music.

The sound track Thursday night at the Bowl was the latest merger of jazz and classical traditions with the West Coast premiere of Wynton Marsalis’ new Concerto in D, along with Aaron Copland’s all-American Symphony No. 3.

Marsalis is not only one of America’s finest jazz trumpeters but also, as an educator and the artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, a classicist in his own right, a prime keeper of jazz tradition. His Concerto in D is a violin concerto, and a big one, that ranges through as many regions and aspects of American music as probably any concerto ever has.

Written for Scottish violinist Nicola Benedetti, making her L.A. Phil debut, it was given its first performance with the London Symphony Orchestra in November. The L.A. Phil is one of a number of commissioners of the score. The conductor was Cristian Macelaru, who also led the U.S. premiere earlier this month with the Chicago Symphony.

A big concerto indeed. In London, it lasted 50 minutes, and Erica Jeal in the Guardian wrote that it felt like the longest concerto ever written. It has slimmed down since to a still significant 38 minutes. It may have needed editing, but I wonder. The impression at the Bowl on Tuesday was of a whirlwind campaign swing through swinging America with not enough time to develop its many, many ideas.

Marsalis does like to go on as his big symphonic works given at the Bowl — the oratorio, “All Rise” and “Swing” Symphony — proved. But he also has a lot to say. The four-movement concerto begins in tribute to Gershwin, with a Rhapsody. The movement opens with a quiet solo violin lullaby and rises through everything from habanera and rustic dance (subtitled “Distant Ancestral Memories”) to spiritual and military march. The other movements are Rondo Burlesque, Blues and Hootenanny.

There is considerable changeable incident at all times. But there is also the consistency of Benedetti’s soulful, gorgeous classical sound. Her job is not to bring the character of a jazz violinist, which she never pretends to be. The orchestra gets all the jive.

Even in the Blues movement, the wonderfully long-lined spiritual heart of the concerto, the brass wails like banshees. In the Hootenanny, L.A. Phil players clap and stomp their feet. Nothing, however, takes away from Benedetti’s rambling but luxurious solos, which she plays with loving intensity.

Let Concerto in D, once more, feel like the longest concerto ever written. Not every work needs formal constraint. We live in a country where long conversations in our music and our politics could just lead to something.

The problem with Copland’s Third Symphony is grandeur. The expectation was that the composer of “Appalachian Spring” could, in a victory symphony premiered in 1946, provide The Great American Symphony.

For my money, Copland came pretty close, but it’s a touchy symphony that begins with elegiac tone and ends by elevating the composer’s famed “Fanfare for the Common Man,” written to celebrate and spur on American soldiers in World War II, to heroic heights. When performed without grace, it can sound a little like establishment political hyperbole.

Overstatement clearly needs avoiding. The composer’s own performances stand back, allowing startlingly rhythmic freshness and somber tunefulness, the unfurling of musical invention, to offer America a poised musical road map for moving forward without undo pretension.

Macelaru operated differently, treating Copland more in the manner of Shostakovich. He brought a heavy hand to accents, and the orchestra struggled under him to make natural syncopations sound contrived. But in one of those rare, yet necessary, moments when nature steps in for the good at the Bowl, a chorus of coyotes in the hills joined the flutes in a considered, careful serious slow movement, and Copland’s symphony suddenly belonged.

A bold performance of Copland’s “An Outdoor Overture,” written for a school orchestra to play indoors, opened the program as professional big-boned outdoor music. Here, happily, hardy music could take it.

by Mark Swed

Source: Los Angeles Times