Nicola Benedetti Performs Wynton Marsalis’s Violin Concerto in LA Phil Premiere

Jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis’s new “Concerto in D” for violin is a brainstorm from a genius brain, but it’s a storm that may yet need more taming.

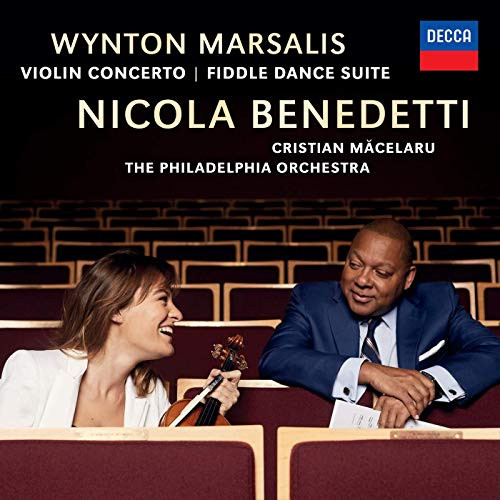

The piece was written for Scottish violinist Nicola Benedetti, who performed it with enthusiasm and stunning technique at her Los Angeles Philharmonic debut Thursday night at the Hollywood Bowl, with Cristian Macelaru conducting.

While Marsalis, who is director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, is known primarily as a master of that genre, one could not call this piece a jazz concerto. It’s more “American eclectic,” or maybe even “world eclectic,” with a dense landscape of musical ideas and unique textures for orchestra and violin. In fact, there may be enough ideas for about 10 concertos; and therein lies both its promise and its problem.

The piece appears to still be under revision; while the London premiere in November reportedly lasted 50 minutes, Thursday’s performance clocked in at about 38 minutes. Scottish violinist Nicola Benedetti played the piece with full commitment and mastery, still reading from the score, which may yet undergo further changes before its next performances, October 27 and 29 at the Kennedy Center, with the National Symphony Orchestra.

The first movement, called “Rhapsody,” began with the solo violin, then went in many directions: an episode that sounded like musical pointillism over a jazz beat; then a high dive from the violin and the orchestra bursting into muscular marches. There were octaves, ghostly violin-playing, double stops, a whistle, even a helicopter (admittedly, the helicopter over the Hollywood Bowl was not likely in the score!). In another moment, the music blossomed in the orchestra like sunshine. Every idea was well-executed, but as a listener, it was hard to hold on to any of it. The end was wonderfully unique: a stomping in the orchestra, and high over that, the violin playing something like a Celtic step dance, which all seemed to wander away at the close of the movement.

In the second-movement “Rondo Burlesque,” the music was groovy, but it never settled into a groove, with its ever-changing meter and mood. Benedetti’s joy in playing this was wonderful to watch, not to mention the way she executed so many effects — a complex mix of fast fingered octaves, glissandi, double-stops and more. My favorite part of this movement was the end of it: jazzy pizzicato, strumming with both the right and left hands.

This segued into “Blues,” the movement which felt most cohesive in mood, the orchestra uniting around bluesy-sounding chords. Benedetti’s violin sang, and the musical line felt longer and stronger, building tension and holding attention. Benedetti seemed to spin an epic tale, which had moments of great noise as well as the whispers that ended the movement.

The fourth-movement “Hootenanny” included clapping, stomping, muted trombones and a lot of double stops for the solo violin. It receded at the end in a similar way as the first movement, with the violin singing a Yankee-sounding song, fading away into the distance.

Throughout the concerto, Benedetti displayed her strong musicianship, superb technique and ability to personify the things she played. I hope to see her again soon onstage with the LA Phil. I’m also still very interested in Marsalis’s work; while Benedetti asked him to make the violin concerto harder for her, as a (totally presumptuous and picky-ass violinist) member of the audience I’d probably ask to revel a little longer in each idea, which might mean hearing fewer of them, but hearing them through.

The night’s program included all American music, the other two pieces being works by Aaron Copland: “An Outdoor Overture” and his Symphony No. 3.

The music of Copland, with its open harmonies and ample brass and percussion, has no trouble filling a big, outdoor space such as the capacious Hollywood Bowl — particularly the large-scale Symphony No. 3. And the LA Phil had no trouble showing its grandiose side, with good clean solos, in-tune tympani, bold string playing — and a lot of musicians wearing ear-plugs (I don’t disapprove, musicians should protect their ears when the music gets this powerful). A special shout-out to oboist Marion Arthur Kuszyk for some great playing in the fourth movement, and to our own Nathan Cole, who was playing concertmaster. (Yes, without a shoulder rest!)

Copland began composing his Symphony No. 3 the same year as the premiere of “Appalachian Spring,” and to my ear it’s a continuation, with the most obvious resemblances in the Scherzo movement. Of course, there are no “Simple Gifts” in the symphony, and the last movement takes its theme directly from Copland’s majestic and unforgettable “Fanfare for the Common Man” and grows organically from there. Copland was a master of exploiting a musical idea, and though this symphony is not played as frequently as his other works, it holds up.

by Laurie Niles

Source: Violinist.com