Taking Back the Blues: A Conversation with Wynton Marsalis

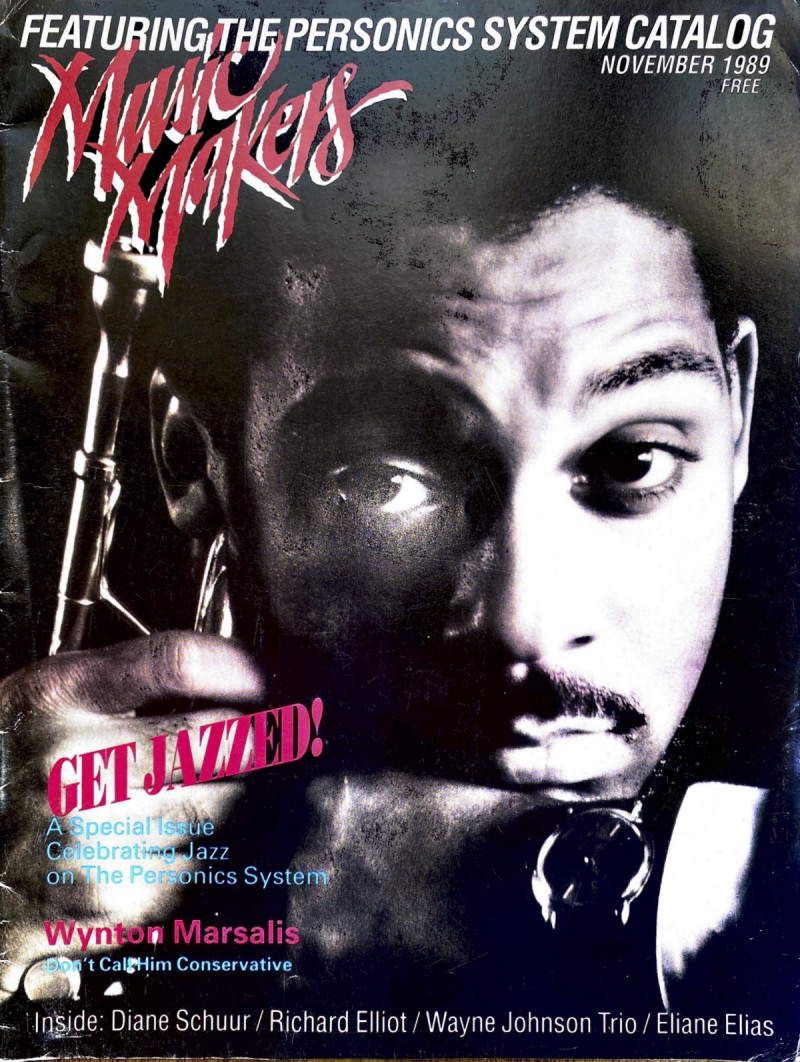

Cover: Music Makers (November 1989)

In the packed-dirt courtyard behind Stanford University’s Frost Amphitheater, Wynton Marsalis entertains a crowd of hearty fans who have ventured backstage to meet him. The trumpeter, who an hour earlier led his band through a concert of grand and, at times, commanding music is polite and disarmingly quick-witted. He graciously signs autographs and poses for photos with people of all ages and races. A bonafide superstar, Marsalis resembles nothing so much as a minister meeting his flock on the church lawn after a service.

Marsalis is a man of passionate convictions with a willingness to speak out that has not always endeared him to the press. Conversing at his apartment in New York City, he is simultaneously eloquent, contentious and defensive. Early on he says, “There’s no reason to talk about what I’m doing – if I played basketball or if I had turkey last night. Why [should people] pay for a magazine when they can take that money and buy themselves a turkey, rather than read about how I ate it. I mean, I will try to answer your questions intelligently and say something that will help those who are seeking to understand the music.”

Marsalis was born on October 18, 1961, in New Orleans. His father is pianist/educator Ellis Marsalis; his older brother is saxophonist Branford Marsalis. His musical experiences run the gamut from teenage funk bands to classical training at Julliard to brief but significant apprenticeships with Art Blakey and Herbie Hancock. He has won Grammy Awards for bothjazz and classical albums.

Let’s begin by talking about the three songs from Marsalis Standard Time, Volume 1 featured on The Personics System. These are Ellington and Tizol’s “Caravan,” Johnny Mercer’s” Autumn Leaves” and the Duke/Hamburg chestnut,” April in Paris.” Considering your reverence for jazz composers and compositions of the past, are you in some way trying to use your popularity to put these songs before a new audience?

[Emphatically] No. I did these songs because I had to learn how to play them. Standards and blues-these are the fundamentals of jazz, and the reason we had to do these is because we saw, as jazz musicians, that these fundamentals weren’t being addressed. They’re being replaced with political rhetoric and social jargon, instead of music. How is somebody who grew up in the seventies going to learn how to play blues? I mean, do you think we were just born with that? You have to make a conscious decision to learn how to play them. No, man, I’m not trying to sell Ellington or any of these people to anew audience. Their music is the cornerstone of American musical culture. You’re doing yourself a favor by checking it out.

So the point is to go back and learn how to play …

It’s not like you’re going back, because all of education is like that. Very few people are learning compositions that are current.

That’s what education is about, that’s what the study of history is about.

Yeah, yeah, it’s going back, in that sense.

Listen, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. I’m not a critic. I don’t have any particular ax to grind.

Yeah, okay. I’m talking to you that way ‘cause I’m so used to that. I mean, I been through this so many times with cats who don’t understand, who are trying to sell guitars and shit. But the reason I don’t like to say “I’m going back” is that I want you to understand that if something is good it’s always current. People think that going back means being nostalgic, but when you don’t know something, there’s no way it’s nostalgic.

There are those who have labeled your music conservative, that it echoes the type of acoustic jazz Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock were playing in the sixties.

[Those critics] don’t even know what we’re doin’. Listen to what we’re playing on Live at Blues Alley. That ain’t conservative. There’s no way for it to be conservative. They don’t know anything about mmic so they say, “It sounds like something I heard.” It’s like somebody who’s never listened to classical music listening to a Beethoven string quartet and a Haydn string quartet and saying, “Damn that Beethoven! He sounds like Haydn!” Well, yeah, on a certain level, he does sound like Haydn. And so does Stravinsky. And so does any orchestral music, if you don’t know what the difference is. That’s what the cultivation of taste is about.

Then let me play the dumb journalist. What’s one element in Live at Blues Alley that makes it impossible to label as conservative?

Just the rhythms we play. And the fact that they’re resolving in time properly, with everybody in the band playing a different rhythm. It’s an extension of things that Mingus was doing, and Monk and Miles. Now, in no way am I saying that we’re hipper than that; I’m just saying it’s an extension. I mean, we’re trying to get to the same level of understanding and musicianship that they were on, but the forms and the way we improvise as a group – that’s not a direct rip-off of other people. But we don’t play enough blues to be considered with those musicians. That’s the element we really need to work on.

What do you mean you “don’t play enough blues”?

I mean, we have emotion in the music, and it’s blues emotion, but it’s not developed through the blues idiom like it should be.

That’s odd, because at the Stanford concert I felt that we were being taken to school on the blues. Blues 101.

[Laughs] Yeah, well, we’re trying to go to the class, too. That’s what we’re trying to do, learn how to play blues right now.

And so we’re invited along?

That’s what art is about – if people will experience it. They’re seeing somebody trying to give order and logic to something human. I mean, when people come into contact with the music and really check out what we’re doing, they get the feeling that we’re about them. I’m honored that they come to check the music out. I’m happy to be on the gig, and so are the cats in the band. I thinkpeople can sense that when we play, even though we don’t talk that much or crack jokes. They know we’re trying to bring something of value.

Let’s return to the central question: Why is it important to learn to play the blues now? Today. 1989.

The blues is the basis of the music. If you can’t play the blues you can’t play jazz. The blues is something that all the musicians once learned how to play; they weren’t born playing it. But in my generation people had stopped playing it. That’s why it became almost impossible to produce jazz musicians. I mean, the blues is everything, man. It’s a form, it’s a system of harmony, of melody. Ellington used the blues idiom better than any musician that ever lived. And Monk? Monk’s music is blues. Even in the tunes without blues chord changes you hear the sound of the blues. Blues is like water. You know what water is like? If you don’t have water you’re not gonna make it. I mean, you can make it with some water for a long time, even if you don’t have food. And what happened with the social breakdown that occurred in the late sixties and seventies is that people stopped addressing key elements of what their society is about, and in our case it was replaced by a reduced version of the blues. It’s like in gospel music. You had people like Mahalia Jackson; but all the shouting and screaming that people do today has got nothing to do with the spiritual substance of that music.

So it’s a commercialization of that music?

It doesn’t have to be for commercial purposes. It’s like a preacher who’ll get up and scream and shout and think he sounds like Martin Luther King. There’s years of education that went into that, to get somebody that sounded like King, that had his integrity. You can be a very smart man and still not have that. It’s like putting a Rolls Royce body on a Vega. I mean, it’s gonna look like a Rolls Royce, but underneath it’s just a Vega. You understand what rm saying?

So the intent doesn’t matter. It’s just that the substance is reduced because enough time wasn’t taken to learn the form.

Definitely. It’s like when you’re growing up you imitate stuff you hear an adult say.

Sort of like the difference between, say …

Somebody like me and Louis Armstrong. Although in the case of Louis Armstrong you just have to be him. I mean, you can’t practice your way into being a genius like him. But let’s take other musicians who are not Louis Armstrong but who are really great trumpet players, which is what we have a chance to become if we practice. The difference between us and them is not their experience, how they grew up, but that they knew how to transfer their experience into the American idiom, the blues idiom. Whereas in my generation nobody was really trying to do that. Our whole thing was to try to make money and play something popular.

Let me bring one of your favorite voices into this, Albert Murray, whom I’ve been reading on your recommendation.

That’s The Man.

Your recent album, The Majesty of the Blues, seems inspired by his work, in both its anger and its humor.

I’m glad to hear that.

In The Omni Americans, Murray says that “the blues tradition [is] a tradition of confrontation and improvisation.” What does that mean to you?

The blues is the essence of heroism. What we mean by confrontation is that the blues is willing to deal with whatever is going on in the world, and the improvisation is the joy and the fun part. The confrontation is like when the blues identifies things that are wrong. It don’t matter what the words are. Like Robert Johnson will have a verse: “Girl I knew left with my best friend/Some joker got lucky, stole her back again/Come on in my kitchen, it’s gonna be rainin’ outdoors.” So there’s confrontation right there, and that’s a whole story. That’s the key to what the blues is about: identifying that it’s rainin’ outside, but if you come in it’s gonna be cool. That’s the improvisation, a way to help you deal with what you’re confronting. Like David and Goliath. David had to improvise. Everybody else went out there and didn’t improvise, so they didn’t ‘‘hook it up.” Whereas David said, “Oh, well, what can I deal with here? A rock!” Or the Trojan horse. They improvised. So all through history we find that those who improvise hook it up.

And that’s the heroic act?

It’s heroic in that it allows you to face adversity with joy and style. Everybody says the blues is sad, but it’s not sad. It identifies something sad and gives you an alternative to that, which is feeling good. Sometimes just identifying a problem can make you feel better.

What is the adversity that inspires you?

There’s adversity all over in life for everybody. I mean, I have the same adversity that faces everybody. “There’s a bullet for every behind,” like my great uncle used to say, “a bullet for every ass.” And we all get our share.

I’m not looking for what happened last Wednesday. I’m talking in a larger sense. I mean, you’re more than sunply a musician. The music and the fate of the music are obviously of tremendous importance to you.

It’s the fate of our whole country. Even more than the music. Of our culture. Of our people. The men and the women.

In the sermon on The Majesty of the Blues, you and writer Stanley Crouch worry about a “premature autopsy” for jazz.

Well, that’s a metaphor. Everybody’s always claiming that jazz is dead, that nobody is playing it, that they can’t play, that they’re not doing something new. So when we say’‘beware of premature autopsies” we’re saying that the music is not dead. People are playing and enjoying it all over the world.

But many people do feel that a great deal of jazz today is a pale imitation of what had gone on before.

If somebody goes and hears Sweets Edison play, they’re not hearing a pale imitation. Or Tommy Flanagan. That’s not a pale imitation. Or Hank Jones. Art Blakey. Max Roach. Betty Carter. That’s six people I’ve just named off the top of my head. That’s not a pale imitation. Now if they go hear jazz musicians playing pop music, that’s a pale imitation-a pale imitation of pop music. In terms of blues feeling, the people in our generation have a long way to go.

Now you’ve said it again: “Not enough blues feeling.”

It’s a spiritual thing. Blues comes from the church tradition. That’s the element that people call soul. It relates to an understanding of humanity that has to do with love and a pursuit of beauty and elegance. It encompasses all of the morality of music, the integrity, majesty, heroism and humility. Like when you listen to Louis Armstrong play, you hear a certain type of majesty and nobility that comes from him being a certain type of person. That’s the element of music that you can’t play around with.

You have to realize that the songs of our generation are not as romantic as the songs of prior generations. It’s a whole different thing, just musically, growing up with popular songs like “Body and Soul” or “It Never Entered My Mind.” It’s gonna be different from growing up with “Tear the Roof Off the Sucka.” [laughs] You know what I’m saying? And we’re just talking about the lyrics; you can extend that same thing into the harmonic and melodic regions.

But aren’t you comparing songs written by adults to songs written by adolescents?

Yeah, the people who wrote those songs weren’t adolescent, but sometimes you have to address the fact that the American popular song is in a state of decline. That’s unarguable. I mean, we can’t say that we’re producing writers like Richard Rodgers, Duke Ellington, Hugo Wolf, Cole Porter or George Gershwin. The problem is that those who are writing about the music are prejudiced against music they don’t know. We have a fast food conception of art which says that because Duke Ellington is dead his music is no longer with us. As long as we have that attitude we won’t produce things of value. Ideas live forever. This is how you make sure your progeny is strong, by making sure that the finest ideas are promoted. But even when Ellington was alive and writing all that great music at the end of his life, everybody was saying his music is not as good as it was.

Such as The Sacred Concerts?

The Sacred Concerts, The Queen Suite, Afro-Bossa, Such Sweet Thunder, AfroEurasian Eclipse, The Latin American Suite, The Far East Suite.

Do you have any plans to tackle some of Ellington’s later stuff?

I’m not equipped to. But I am trying to write music now that reflects that I’ve listened to it, and am influenced by it, which is more important than necessarily recording one of his tunes because his records are still available. I try to encourage people to check his recordings out. Ellington is the ultimate American musician. His music is the most comprehensive, most well-crafted. And you never hear any chaotic elements.

What is it that has caused you to take on the resurrection and preservation of the American popular song?

It’s not just me. There are many others. It’s just that I have the forum and that I am indefatigable in that way. I won’t get tired. I was fortunate to grow up with my father, and I’ve had so many teachers. I go to Al Murray’s house every chance I get and rap with him, and he’ll go to bookstores and get books for me. There have been so many older musicians who’ve looked out for me and given me this philosophy that there’s no doubt that it’s correct and that it’s my responsibility to the music and the people to just deal with it. There’sjustnodoubtthattheAmerican popular song has declined. There’s no doubt that you have to learn how to play blues to play jazz. There are other things that fall in the realm of opinion, like whether you like the way somebody plays, but we’ve been talking about aesthetic points and on these we can pretty much come to a right and a wrong.

I’m not trying to senselessly attack people, which is what I think has been blown out of proportion. I’m trying to get something accomplished. I go to schools and teach kids myself. I mean, with this culture, that’s what the deal’s got to be.

You have to learn something and try to refine it and just keep repeating it. That’s what Ellington did, and it just got better and better. No matter what people said about him-that he couldn’t write long forms, that he was too European, that the band couldn’t swing, that his best years were 1938 to 1941, that the music was too pretentious-it just didn’t make a difference to him. His response was, “Well, here’s some more music.” Hopefully we can develop the type of clarity that his thing was about. Identify younger cats who are serious and who are dedicated to really creating music, cats that have a certain type of spirituality and humility, a certain love, and can bring that into the scene, who will live up to what Ellington and Sweets Edison and all those people represent. That is what young people should do: live up to the best of their heritage.

by Peter Shwartz

Source: Music Makers (November 1989)