Trumpeter Marsails personifies jazz

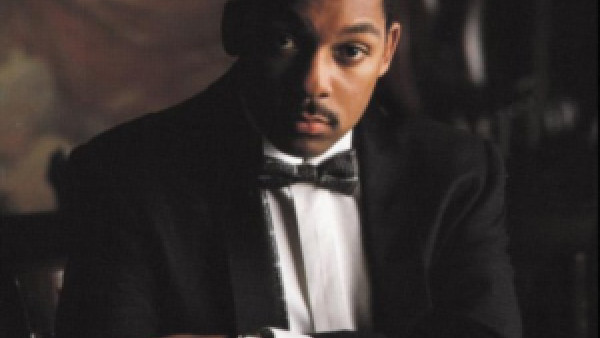

TALENT, VISION and determination have made the brilliant trumpeter Wynton Marsalis a provocative figure in jazz, with a productive parallel career in classical music.

Since Marsalis first rose to prominence in 1982, however, he has become something more: not only an ambassador for jazz, but to many, a living definition of jazz, the way Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong were in their lifetimes.

This wasn’t his doing, of course, yet it’s a safe bet that people who don’t follow jazz (or classical) will recognize his name.

It’s interesting to speculate how many of those people will attend when he plays May 11 at the Centennial Concert Hall with his band—pianist Marcus Roberts, Reginald Veal on bass, drummer Herlin Riley, altoist Wessel Anderson and tenor/soprano player Todd Williams.

Formidable presence

Some call him arrogant, even those who hint that he’s earned the right to the attitude. Yet Marsalis sounded shy when the living symbol angle was reached in a recent telephone interview.

“Well, I don’t really feel that,” he says. “I hope that’s not true. There are so many of the great jazz musicians out there still playing.” Only 27, not much more than teething age by the standards of jazz experience, he is a formidable presence.

There’s his music, of course, with the virtuoso trumpet technique that has earned prodigious accolades in two musical worlds. There is also something more, less easily defined, a certain iron in the soul by which he’s held fast against commercial pressures (such as his record company’s early attempt to record him in slick synth-pop settings), as well as criticism seemingly based, for the most part, more on his personality than his playing.

Altough his jazz is too close to post-bop modes for innovation, his peerless tone and astounding technique must be applauded, and his sheer presence has given the jazz world a healthy shake.

He’s the man with the eight Grammy awards (the first to win in both the jazz and classical categories in the same year), the crisply tailored cat who put jazz back into sharp Italian suits, the historian — and how appropriate that he was born in New Orleans — and the teacher.

Arrogance doesn’t come over in the telephone interview, but confidence does, along with a tint of wariness — too many unfortunate interviews, maybe — and a sardonic but genial humor.

Call it faith in himself. He’ll allow dissenters their due, but that won’t stop him playing. “I have the right to say what I want also. Ultimately, the art form will speak as to who has the most pertinent information.”

One of six sons born to pianist Ellis Marsalis, Wynton received his first trumpet at six, a gift from New Orleans landmark Al Hirt. Serious studies didn’t start until Marsalis was 12, when he first tackled classical charts.

He played first trumpet in the New Orleans Civic Orchestra while in high school. At 17, his chops were so strong that he was accepted into the Berkshire Music Centre summer program at Tanglewood, where the minimum age for enrolment was 18.

Through that time he kept up with jazz studies and blowing, and the following year saw his star rise in that firmament. Signing on with Art Blakey, that master drummer and teacher, Marsalis fast became the latest cat to watch in Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

Marsalis disdains the praise now. “Well, yeah, I didn’t know anything. I was just up there playing.”

SUBSEQUENT to touring with Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams and Ron Carter (an earlier pride of young lions), Marsalis cut his first jazz date under his own name for CBS. One year later, the first of his classical titles was issued on CBS Masterworks.

A few others have performed convincingly in both idioms, Benny Goodman for one, but none have matched Marsalis’s track record. Four classical sets have been released so far, and there’s more in the can. Including jazz sessions, in fact, he says he has more music waiting in the CBS vaults than he has on the market.

Is he trying to make a point that jazz musicians can play that music?

“That was maybe my point when I was 12 or 13 but now I don’t really care,” he replied. “Because, you know, prejudice survives all evidence, so that doesn’t make a difference to me. Mainly I just play it because I really enjoy playing it.”

Such crossovers have often met with suspicion, tinged with racism in the instances of black musicians venturing into a traditionally white province. Marsalis will have none of that.

“I don’t recognize race in music. I believe if you want to play a style of music you should play whatever you want to play. It’s the art form that will decide how far you go in it, not any random group of people.”

Ignorant critics

That group includes critics. Marsalis reads them, and doesn’t begrudge them a living, provided they have the knowledge to support their opinions.

This disqualifies most of them, he feels. When asked if most critics are well informed, he replied, “Who, in jazz? Oh, none of them.”

Really?

“Maybe two,” he conceded. “If you just want to get an instant job and not have to know anything about it, just be a jazz critic. They don’t know anything, really. They have record collections, but they don’t understand the philosophy of the music.”

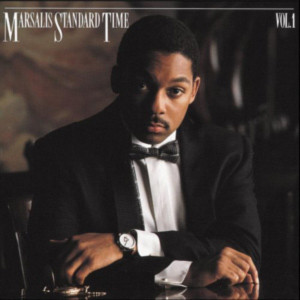

His latest jazz studio album, Marsalis Standard Time Vol. 1, is virtually all evergreens (Cherokee, April in Paris, Autumn Leaves, etc.). Was that, in part, a lesson to young players to remember the past?

“Well no, I’m attempting to learn it myself,” he says, laughing again before explaining that he’s still learning the jazz art of playing on the chord changes.

He’s complained in the past that too few young jazz hopefuls know the history of the music and its past masters, a situation he ascribes to “the whole pop mentality: live for the moment and knowledge is not important, it’s the feeling that counts.(But) if you don’t have knowledge, you’re not going to get the feeling.

“But it’s not just jazz,” he adds, “it’s the whole cultural education.”

To that end, he’s contributed considerable time to teaching the history to young players. Recently, for example, he’s led a high-school band that tours New York, Philadelphia and Washington D.C., playing the later music of Duke Ellington. He’s also started a program in the New Orleans public school system, devoted to the early music of that city.

As far as his own history is concerned, he has mixed feelings, and rates his CBS catalogue as a process of development. “Some of it I don’t like, but it just shows a steady development.”

By Randal Mcllroy

Source: Winnipeg Free Press