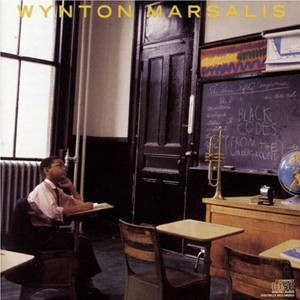

Review: Black Codes (From the Underground)

When Wynton Marsalis first emerged as a 19-year-old prodigy in Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, the trumpeter’s ardent defense of acoustic jazz was heartening. Here was a musician with enough technique to win classical Grammys and enough charisma to land on magazine covers, and he was devoting himself to a tradition whose rewards were more esthetic than financial.

Somewhere along the line, though, Marsalis’ artistic crusade changed from the positive to the negative. Recently his put-down of rhythm and blues and rock ‘n’ roll, and his purist definition of jazz have made him sound a bit like a reformed alcoholic. He publicly criticized his brother, saxophonist Branford, and his longtime pianist Kenny Kirkland when they appeared on Sting’s jazz-rock solo album. When they went on tour with Sting, Wynton fired them from his band.

Wynton Marsalis talks a lot about the Afro-American musical tradition, but somehow he can’t quite find a place for the humor and dance rhythms of R&B within that tradition. Not surprisingly, his music is somber.

Marsalis could learn a valuable lesson from Lester Bowie, the trumpeter for the Art Ensemble of Chicago. The AEC has devoted itself to “Great Black Music: Ancient to the Future” for much longer and with much less remuneration than Marsalis, and it has no trouble at all incorporating R&B into its jazz. On his own solo album, Bowie has delighted in taking R&B standards from the ’50s and transforming them into tour-de-force performances that combine the sassy, hip-shaking humor of R&B with the inspired invention of jazz.

Wynton Marsalis’ new album, “Black Codes (Notes From the Underground)” (Columbia FC 40009), is a superb record. The trumpeter has never written better material, and he has never elicited better performances from his quintet. In fact, the brilliant playing by Branford Marsalis and Kenny Kirkland illustrate why Wynton is soon going to regret his decision to let them go.

Marsalis’ album is firmly in the post-bop tradition of the pre-electric Miles Davis Quintet and Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. Marsalis is refining a tradition rather than extending it. By contrast, Bowie has created a whole new group, Lester Bowie’s Brass Fantasy, and a whole new sound on their album “I Only Have Eyes for You” (ECM 25034-1 E). Working with eight brass instruments and one drummer, Bowie creates a heady new blend of New Orleans brass band music, doo-wop harmonies and avant-garde jazz.

Marsalis’ technique on the trumpet is so overwhelming that Bowie can’t even touch it — nor can any trumpeter since Dizzy Gillespie. On the title track, Marsalis sketches out his theme with diamond-hard notes that never once weaken. Every phrase is concise.

His brother Branford’s technique is not quite so overpowering, but the saxophonist (older by a year) has a playful sense that Wynton lacks. While the trumpet solo on “For We Folks” aims for a stark beauty, the soprano sax solo validates the title by giving the attractive theme a warm accessibility. On the turbulent, jagged rhythm of “Chambers of Tain,” it is Branford’s tenor sax and Kirkland’s piano that burst loose in the cathartic torrents of notes the tune requires.

On “Delfeayo’s Dilemma” (written for teen-age trombonist Delfeayo Marsalis), Wynton shows he can maintain his precision and thoughtful phrasing even at galloping tempos. His best moment, though, comes on his gorgeous ballad “Aural Oasis.” His melancholy trumpet seems to sigh as it makes its reluctant confessions.

Ironically, St. Louis’ Bowie shows more feel for New Orleans’ tradition of brass bands and R&B than the Crescent City’s own Wynton Marsalis. Obviously inspired by the Dirty Dozen Brass Band, Bowie has formed a group comprising four trumpets, two trombones, a horn, Bob Stewart playing bass lines on the tuba and Phillip Wilson playing snare and bass drum.

Unlike the Dirty Dozen, though, Bowie is as interested in harmonies as in rhythms, and he often arranges the horns like voices in a street-corner doo-wop quintet. Before long his iconoclastic AEC spirit comes to the fore, and he is subverting all these traditions with improvisations that are as stimulating as they are unorthodox.

The title track of “I Only Have Eyes for You” is a 10-minute version of the Flamingos’ 1959 doo-wop hit. The horns capture the languid romance of the original as they swoon through the memorable melody. Without losing that theme, they begin tossing in asides: squirting trumpet tangents, laughing trombones, harsh shouts and pulsing staccato notes. Before you know it, the group has transformed this familiar ballad into something altogether new and wonderful.

Combining Caribbean and Dixieland flavors, Bowie’s “Coming Back, Jamaica” is firmly in the brass band tradition. Bowie plays odd, dissonant phrases and the horns respond with cheerful parade shouts as Stewart’s tuba supplies a bubbling rhythm. There is a lively, humorous spontaneity to this piece that’s nowhere to be found on Marsalis’ record. Washington trumpeter Malachi Thompson’s “Lament” and Stewart’s “Nonet” show off the band’s more serious side as murmuring, overlapping horns melt into meditative harmonies. Working like a choir of closely bunched voices, this ensemble can be spellbinding.

The album finishes with a flourish on Bowie’s “When the Spirit Returns,” an original variation on a New Orleans funeral parade. It begins with a gorgeous, sad farewell and then builds into a happy, joking good time. It proves conclusively that both requiems and party music are legitimate parts of the jazz tradition.

By Geoffrey Himes

Source: The Washington Post