Marsalis, Jazzy AND Classical

THE THING to remember about trumpet virtuoso Wynton Marsalis is this: he is only 22.

And the thing to appreciate about Wynton Marsalis is that he seems to be the only one who remembers this fact.

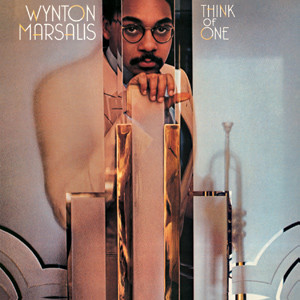

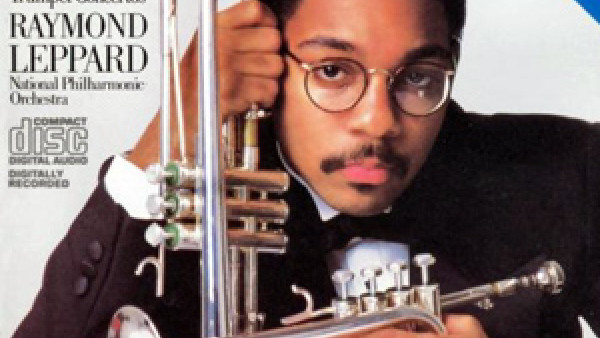

Marsalis is the jazz prodigy whose eponymous debut album walked off with Downbeat’s “album of the year” honors in 1982. At the same time he was named jazzman of the year in his first go-round as a group leader. Now he has become the first American artist to release jazz and classical albums simultaneously: “Think of One” (Columbia FC38641) and “Haydn, Hummel, L. Mozart Trumpet Concerti” (Columbia Masterworks IM37846), pieces of bravado tempered by Marsalis’ keen sense of his own abilities and limitations.

Technically impressive, Marsalis seems content to advance to a higher ground slowly, deliberately. There’s nothing particularly vanguard in his playing; he’s certainly more engaging than innovative. In fact, his acoustic, post-bebop mainstream playing would probably seem retrograde in less skilled hands. Marsalis is smartly allowing himself the space and freedom, and perhaps most important the time, to develop as musician, composer and leader. Eventually, his sound will become distinctively personal, particularly when his passion equals his proficiency.

But at 22, Marsalis is accomplished in two extremely difficult disciplines that are the antithesis of each other. The strict interpretation of classical music is 180 degrees away from the vivid improvisation of jazz, yet Marsalis has both under such control that even the praise of his peers shares an odd harmony (Maurice Andre insists he could become the greatest interpreter ever of trumpet concerti, and Leonard Feather calls him “the symbol for the new decade”).

On both new records, Marsalis is very much the classicist, and it’s lucky for him that the classical repertoire is not nearly as rich as its jazz counterpart. That’s obviously where his heart resides and it’s there that he continues to pledge allegiance to the bop era, drawing this time around from Thelonious Monk (the title cut) and from the Ellington-Strayhorn songbook (“Melancholia”). Marsalis’ playing continues to be informed by the rich groundwork of his predecessors—and frequently acknowledged influences: Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, Lee Morgan, Fats Navarro and Clark Terry.

Unlike his debut, which unveiled Marsalis in the salable context of such well-known players as Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams and Ron Carter (all Miles Davis veterans who have regrouped as VSOP II, with Marsalis), “Think of One” captures him with his remarkable—and remarkably young—working quintet, which includes Marsalis’ saxophonist brother Branford (himself cutting a solo album) and pianist Kenny Kirkland. But this is no Blue Note blowing session or Riverside ramblings: The quintet is tight from experience and powered by youthful passions and energy.

Marsalis, who also wrote three of “Think of One’s” eight tunes and arranged the title cut, completed the circle by producing the album. He mixes a producer’s taste with a musician’s sensitivity, leaving ample room for his fellow players to establish their identities. Brother Branford, who’s possibly the gutsier of the two, comes through regularly, his coltish soprano weaving a sinewy line through “The Bell Ringer,” establishing a middle ground between Coltrane invention and Shorter lyricism. Kirkland, composer of “Fuchsia,” is a graceful, energetic pianist who reminds one of another Wynton (Kelly). His long, fluid lines course through a number of compositions, a current that’s as good as electric.

Marsalis, improvising with an authority and conviction far beyond his years—he knows where he’s going, and how to get there—is an intrepid explorer of textures and nuances. His carefully etched solos burst not only with an expected vitality but with a carefully selected cacophony of moans and growls, smears and squawks that contrast with his absolutely luminous, bell-like tones elsewhere (particularly on a bittersweet muted ballad like “Melancholia”).

Marsalis is sensitive to becoming trapped in a single stylistic bag, and so “Think of One” is something of a variety pack, with its tempi and moods fluctuating even within a single tune. The title cut has a catchy stop-and-go spirit, with the quintet gingerly phrasing Monk’s typically quirky melody, which then serves as a background for a series of bright solos.

“Knozz-Moe-King” kicks the album off energetically with drummer Jeffrey Watts and bassist Phil Bowler (alternating with Ray Drummond on three cuts) powering the affair in Art Blakey fashion; they don’t really let up, but they are thoroughly empathetic to their leader’s motives.

“Later” is a decidedly upbeat blues, with the rhythm section pulsating under the Marsalis brothers’ splendidly inventive explorations. In the playing of the entire quintet, one senses a refreshing idealism fueling—or possibly fueled by—an ambition to grow together and to grow well.

The classical record, digitally recorded with the National Philharmonic Orchestra (of England) under the direction of Raymond Leppard, is brisk and as sonically bright as one could want. Marsalis performs three pieces, the best known being Haydn’s Concerto for Trumpet and Orchestra. It’s a piece he’s certainly familiar with, having first played it at age 14 with the New Orleans Philharmonic.

In his classical guise, Marsalis extends his reverence for musical history and perspective. He’s respectful in his articulation, never intruding or tampering with the composers’ musical line (though he does seem more comfortable being busy than being simple: just listen to the vibrant cadenza that ends the first movement of the Haydn or his exquisite embellishment of the second movement of the Mozart, both very much in the classical tradition but with touches of home-town New Orleans as well). His interaction with the orchestra is as delightful as his integration with the quintet.

There are some who feel Marsalis’ best work is inspired by live audiences. He can be heard in such a setting on parts of two recent concert albums: “Conrad Silvert Presents Jazz at the Opera House” and “The Young Lions of Jazz.”

by Richard Harrington

Source: The Washington Post