How Wynton Marsalis helped resurrect the musical voice of Buddy Bolden

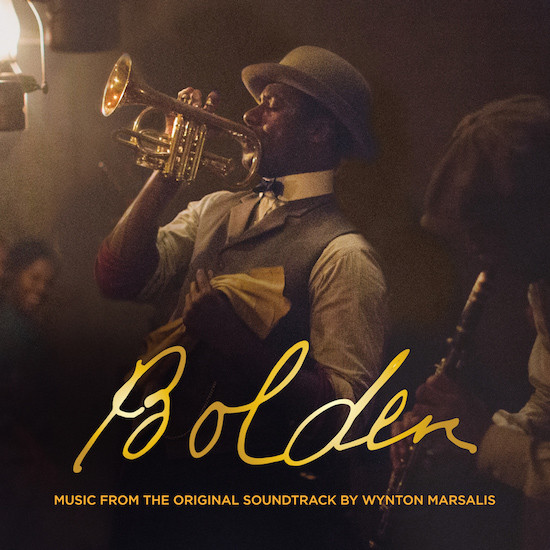

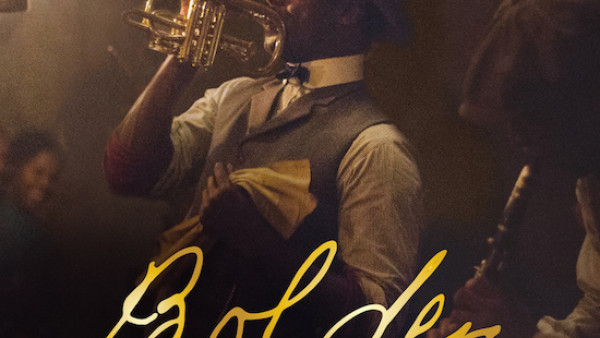

Gary Carr plays Buddy Bolden, and Karimah Westbrook plays his mother, Alice Bolden, in director Dan Pritzker’s 2019 film “Bolden.” (Photo by Fred Norris/Abramorama)

For Dan Pritzker, the decision was a no-brainer. He wanted to make a movie about New Orleans cornetist Buddy Bolden, the mysterious, nearly mythological figure credited with having pioneered the improvisational music form that would become jazz, and he needed someone to provide the “voice” of Bolden’s horn.

And who better to help tell the story of one of the greatest practitioners of early jazz than one of the greatest practitioners of jazz today?

So Pritzker arranged a meeting with Wynton Marsalis, the New Orleans trumpeter and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center whose litany of honors include nine Grammy Awards, a National Medal of Arts and a Pulitzer Prize, and who will perform with his father and musical brothers at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival on Sunday (April 28).

To Pritzker’s surprise, Marsalis jumped at the chance to come on board, agreeing to compose the music for the long-gestating drama “Bolden,” which, after 11 years of shoots and reshoots opens May 3 at The Broad Theater.

As easy as a call as that might’ve been for Pritzker, the decision-making would be decidedly more complex for Marsalis. That’s because, while actor Gary Carr portrays Bolden on-screen, Marsalis plays all the cornet parts for the film. Consequently, it fell to him to figure out what Bolden’s playing actually sounded like.

There’s just one glaring problem: As legendary as Bolden is, no recording of his playing is known to exist. We know he played loud, and we know he played like nobody else. But that’s about it. So, the question becomes, how do you imitate the musical voice of a man you’ve never heard play?

For Marsalis, the answer would involve a bit of informed speculation and no small amount of musical detective work.

“I just wanted to write music, and Dan wanted the same thing, that showed the range of music that Bolden played,” Marsalis said, calling recently to talk about his work on the film. “I wanted to play with a lot of energy and fire and play the hell out of the cornet. I wanted to play with a rhythmic intensity.

“A person who’s playing with more intensity, and emotional intensity, is going to seem like he’s playing loud. The intensity and emotion is going to make it feel loud. It’s much like the effect with the way Charlie Parker played, or Louis Armstrong.”

The thing is, “rhythmic intensity” is a fairly broad description, one that still can be interpreted in a number of ways. To zero in on a more detailed, refined version of what Bolden might have sounded like, Marsalis would have to dig deeper.

So, he said, he explored the music of some of those musicians who played with Bolden, and were thus influenced by him, but who — unlike Bolden — did, indeed, record. Three players in particular provided key inspiration, becoming a sort of musical composite character, Marsalis said.

There was Bunk Johnson, who was known as one of the city’s best trumpeters between 1905 and 1915. There was also King Oliver, whom Marsalis describes as playing “with a great amount of dignity.” And there was Freddie Keppard, a Creole cornetist who played more of a ragtime style but with a certain musical sophistication.

“You put those three players together, and I figure you get a sense of Buddy Bolden,” Marsalis said.

“A sense”: Those are the operative words. Because, just as Marsalis can only speculate about what Bolden’s playing sounded like, Pritzker — though enlisting the help of Bruce Raeburn of the Hogan Jazz Archives at Tulane University for biographical details — had precious few verifiable facts about Bolden’s life with which to work.

We know he was born in New Orleans in 1877. We know he was so revered on the local music scene that he earned the nickname “King.” We know he liked booze and women in equal measure. And we know he was a musical supernova, his career over by the time he was 30, which is when he was sent to the state mental hospital in Jackson after being diagnosed with alcohol-induced psychosis. That’s where he would live out the remainder of his days; he never played publicly again.

Bolden would die at age 54 and be buried in Holt Cemetery, a potter’s field in New Orleans. No one is sure which grave is his.

It’s a story that is as fascinating as it is tragic, but the lack of verifiable details makes the task of trying to turn it into a feature film a tricky one. There are so many blanks to fill in that any filmmaker brave enough to tackle it must by necessity employ a certain amount of literary license, which as often as not invites criticism.

But when Pritzker explained his vision to Marsalis at the first meeting, he used a word that it turns out was key as far Marsalis was concerned: myth.

“He said, ‘It’s a mythic story,” Marsalis explained. “If you’re going to do a movie about Buddy Bolden, it’s got to be a myth.”

In other words: Rather than running from the gaps in knowledge about Bolden’s story, Pritzker wanted to embrace them by filling those gaps with exaggerated elements that, while perhaps not reflective of actual events in Bolden’s life, hint at the sort of larger-than-life figure he has become.

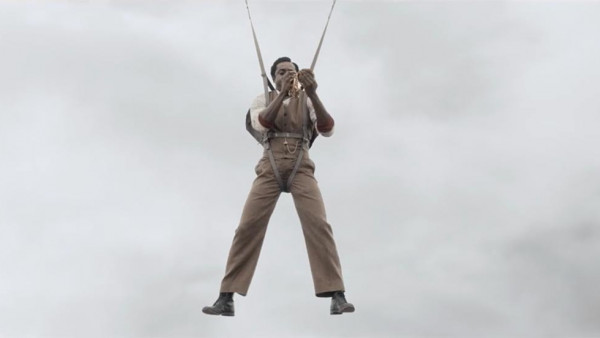

For example, early in the film, Bolden’s manager talks him into raising his profile by parachuting from a hot-air balloon and into a swanky lawn party. Bolden reluctantly goes along with the plan, blowing his trumpet as he floats down from the sky. When he lands, he’s greeted by a crowd that follows him around as if he is the Pied Piper of Hamelin.

Did that really happen? Of course not. But it does provide a certain context, capturing the sort of hold Bolden had on audiences, the sort of musical magnetism he generated.

Marsalis also singles out a sequence set in a factory in which a young Bolden hears the machines whirring away — and hears music in them. There’s no way to know if that actually happened to Bolden, but Marsalis says he’s spoken with other musicians who as children remember appreciating the musicality of a whooshing washing machine or other appliance.

“I feel like it’s one of the most straight-forward uses of music, where the filmmaker wasn’t trying to run from the music,” Marsalis said. “The music is central (to the film).”

Despite the obvious passion and reverence on Pritzker’s part, “Bolden” still has to be seen as a risky project. After all, Buddy Bolden is an icon. People don’t like it when you tinker with their icons.

But when asked if that gave him pause when deciding to participate, Marsalis shrugged it off. Intimidation, it would appear, isn’t part of his game.

“I don’t go into things with a fear of things being wrong,” he said. “You go to the dance, you dance. You don’t go to sit on the wall.”

An Ellis Marsalis Family Tribute, featuring Wynton, Branford, Delfeayo, Jason and Ellis Marsalis, is scheduled for 5:40 p.m. Sunday (April 28) at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival’s WWOZ Jazz Tent.

Mike Scott is the movie and TV critic for NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune. He can be reached via email at [email protected] or on Twitter at @moviegoermike.

By Mike Scott

Source: Times-Picayune