Bold venture is more glorified jam session than fully-achieved work

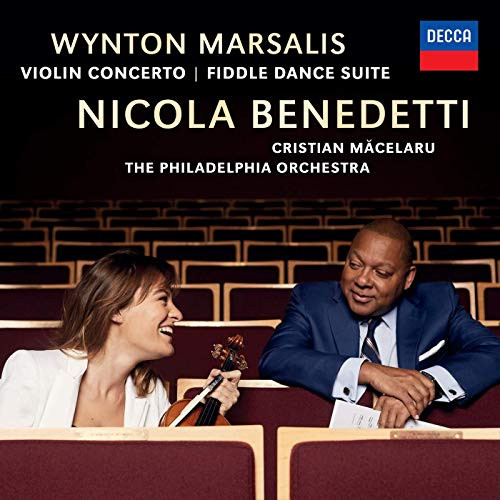

Wynton Marsalis has made several forays across the jazz-classical divide, but his Concerto in D, which was written for – and, more importantly, with – the violinist Nicola Benedetti, marks a bold new departure.

Marsalis may be a jazz trumpeter, but his childhood was pervaded by European classical music, and he stresses the extent to which jazz has been pervaded by it too – by its scales, harmonies, and hymn tunes. He also points to the jazziness of British folk-fiddling, and he loves the versatility of the violin – its ability to play chords, to sing two melodies at once high and low, and to evoke the dance.

Benedetti is by nature a musical explorer, always ready to take on new challenges, and she was persuaded into this collaboration by the promise that she wouldn’t be expected to do that thing which terrifies all classical musicians – namely, improvise.

The composition of this work proceeded via discussion about every bar, with Benedetti complaining that the first draft was too easy, and suggesting that the work as a whole should become a journey through all the potential worlds of her instrument. What she herself found hardest, it seems, was to create an authentically bluesy sound.

In its world premiere at the Barbican, with James Gaffigan and the London Symphony Orchestra providing support, this concerto opened with a Mahlerian lullaby on strings, through which Benedetti’s violin gracefully threaded its way. The tonality then began to veer between classical and jazz, with constant shifts in style and dynamics: one had the feeling that soloist and composer had opened their entire box of tricks, with Marsalis referencing everything from Mississippi blues to the Hot Club de France. In her first cadenza, Benedetti let rip with a melange of ferocious sawing and delicate, high-lying threads of melody: this music was technically demanding. The second movement saw her instrument emitting squeaks and chirps over a wah-wah brass bass, and it ended in a Scottish folk song with a double-stopped violin lament.

The third movement, a celebration of the blues, felt like the heart of the work. Here Benedetti’s playing was convincingly idiomatic, if it also periodically took on a Balkan tinge; although improvisation was not on the menu, this did feel improvised. The finale, ‘Hootenanny’, allowed yet more colours to emerge from the solo violin – I’ve never heard Benedetti project her sound with such mellow warmth – and it concluded with the double basses pumping bravely along while Benedetti’s sound gradually disappeared into the ether.

Yet this interesting endeavour felt less like a fully-achieved work of art than a glorified jam-session, and the other works in the programme served to point this up. The way the LSO played it, there was infinitely more jazzy energy in Bernstein’s Prelude, Fugue and Riffs than in Marsalis’s work, and in a fraction of the time. Stravinsky’s Symphony in Three Movements was a model of compressed brilliance, and Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms – including a flawless treble solo from Ben Hill – really rocked. And what form the LSO was on, with its sax players equal to all Marsalis’s challenges, plus outstanding bassoon solos by Rachel Gough and Catherine Edwards presiding at the piano.

by Michael Church

Source: The Independent