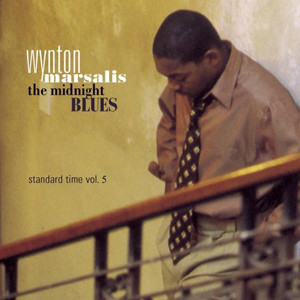

The Midnight Blues – Standard Time, Vol. 5

Like Johnny Hodges and Clifford Brown before him, Wynton has developed the knack of playing ballads as if he were singing the lyrics through his horn, invigorating even the most familiar pop standards and show tunes with a fresh intimacy and bite. He is accompanied by Eric Reed on piano, Reginald Veal on bass, and Lewis Nash on drums, and backed by a string orchestra arranged and conducted by Robert Freedman. Whether you’re currently in love, nursing a broken heart, or in hopeful quest of new love, here’s the perfect soundtrack for your emotions.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Quartet with Strings |

|---|---|

| Release Date | April 28th, 1998 |

| Recording Date | September 15-18, 1997 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | CK 68921 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| The Party’s Over | 6:03 | Play |

| You’re Blase | 6:40 | Play |

| After You’ve Gone | 5:48 | Play |

| Glad To Be Unhappy | 7:47 | Play |

| It Never Entered My Mind | 6:07 | Play |

| Baby, Won’t You Please Come Home | 5:30 | Play |

| I Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out To Dry | 5:59 | Play |

| I Got Lost In Her Arms | 5:07 | Play |

| Ballad Of The Sad Young Men | 5:51 | Play |

| Spring Will Be A Little Late This Year | 4:30 | Play |

| My Man’s Gone Now | 4:37 | Play |

| The Midnight Blues | 11:58 | Play |

Liner Notes

Technically, The Midnight Blues represents a harking back to the more traditional, “old school” approach to recording. Rather than having recorded each element of the ensemble separately and at different times – e.g., rhythm section, strings, and finally trumpet (a technique known as overdubbing) – all of the musicians were, in this case, captured on a state-of-the-art digital medium performing in the same room and in “real-time.” Furthermore, the musicians were not individually placed in isolation booths – enclosures that are frequently used to prevent one instrument from “leaking” into another instrument’s microphone.

One advantage to this style of recording is that it permits the musician to participate in a free and spontaneous exchange of ideas with the other musicians. This “instant feedback” actually helps to shape the direction and content of an entire performance. Another advantage is that it enables the performers to balance the music naturally, thereby producing an aural experience on tape commensurate with what is actually taking place in the hall.

For all of the above to succeed, the correct selection of recording hall was critical. In this case, in our pursuit of the appropriate character and acoustics, we decided on The Grande Lodge of the Masonic Hall in New York City.

That alone, however, was not enough. After all is said and done, it was the true artistry and expression of Wynton Marsalis, his accompanying trio, and the arrangements of Bob Freedman which breathed new life into these wonderful ballads.

–Steve Epstein

MIDNIGHT BLUE:

TWO WILL FIND A WAY

Ardella Jefferson had memories with wings so strong that they made her into a factory of passion twenty-four hours a day. They homed in on her. She could be blasé about nothing. That was the way she was, when the party was going on, when t was over.

Sometimes the party was over while it was going on. Yes, there were the times out in the evening world when the night had the ruminating atmosphere of a ballad, but the men were sad and too young to interest her other than to get Ardella to remember the power of feeling that arrived when she was in the first swelter of her womanhood and learned not to sink into fear upon hearing herself say, “Baby, won’t you please come home.”

Her way of being was in place. The woman was toying around through her apartment in some silly fuzzy slippers, waiting for the coffee water to boil. Her slip and robe felt just fine. At the window, she was eating a perfect cookie and getting some recollection done.

To be close to God is the bread of angels: to remember love is to hear the trumpet and the strings.

Ardella was smart, just about as smart as you could get short of being somebody like Albert Einstein. But all she produced was feeling and all she was interested in was feeling. She was too fine to be afraid of the mirror and it didn’t matter whether she was trim at one point or hefty at another; her ability to remain a manifestation of beauty at the ready didn’t falter.

Perhaps one could understand what made her beautiful by getting with the fact that this woman had a captivating glow in her rhythm. It didn’t matter what she was doing, from cooking to reading Derek Walcott’s Nobel Lecture. The Antilles: Fragments Of Epic Memory. She loved where he wrote, “The sigh of History meant nothing here.” That glow of rhythm was in place and showed itself in the way she might turn a big spoon in a kettle or the unnumbered pages of Walcott’s lecture. Let’s not talk about that walk through a museum that could challenge the angelic visions of the masters, or the way she might shake that head or the kind of deep breathing she might inspire when those eyes fell on you. Glowing in rhythm all the way across.

Her glow was an aspect of unswerving faith in the power of giving others their due. She was sensitive; paying attention to herself alone would have made Ardella feel that she was committing some sort of very raw sin. For all that she had been alone many times, alone as many women are in our world, not always waiting for anybody special but learning how to handle the tricky shapes in our world, not always waiting for anybody special but learning how to handle the tricky shapes all the love inside her might take.

Those shapes take on the spiritual form of that trumpet and those strings. They suddenly expand into some kind of a creamy orchestra with a brass cherry on top, the dessert of sound telling Ardella all the things that she preferred to remember about the majesty of whispers and of tenderness, and of the closeness that knows no recurrent definition other than that of an antidote to all the loneliness that makes the soul feel as though it has been compressed into an insect sentenced to abide forever in the scratchy test pocket of darkness.

The view overlooking Central Park from Ardella’s window was always clear. Outside, autumn was throwing in its hand and letting winter take all the time on the table. When spring had the right cards, even if it was late this coming year, it would take the time away from the champion of chill. She wondered if spring was almost glad to be unhappy as it waited for the moment when its green would make it seem as though the cold hadn’t ever entered the mind of anybody.

Ardella had the good fortune of being able to tell the speed of the wind by looking at the trees in the park. Such things helped you get yourself straight. The rain on the window told you what to put on. The temperature of the air let you know when spring had given in to summer. Autumn was when the city was dressed in red and gold. Then there was the snow’s making it clear what you had better wear when you went into the street. Because the change of seasons had always meant so much when she was not by herself, the wing-flapping of Ardella’s memories was strong, too strong to exist only for the purpose of hanging sorrows out to dry. There were also smooth recollections of her sweetest romance; homing pigeons always headed for Ardella’s soul.

That trumpet and those strings: remaking themselves into the psychology of romance, where feeling becomes a way of thinking and perceiving the world, a way of analyzing. That brass, those strings, and those bows always find a way of expressing everything from the very smallest whisper at the right time to the broad strokes of something as clarion as an electric blue silk tie or a shrimp orange dress. Each handed over in a gift-wrapped box with a card on a day that was not a birthday, not a holiday, just a day of acknowledgment that someone was thinking about somebody and could not hold back saying it in a specifically selected way.

Windy out there through the glass and over into the park, windy the way it was when she was right and he was right and they were snuffled up and on foot, looking for a new place in the park where they could stand and talk about feelings. Or explain themselves to each other, or reduce every aspect of their passion to the essence that arrived with a hug. An embrace that had no heating problems as it flowed in all directions, pasting a big feeling of light inside and outside of every little bit of the two of them. Gee, wasn’t I good to that man. Gee, wasn’t he good to me. Now I feel – face it, face it, face – out of place. Well, let me tell myself the way it is so I’ll know the way I am. It comes down to something I knew even before I was lucky enough to know it: I need some love to put me in my place.

Oh, she had had it going on so well at one time above all other times that when the recollection of that way that she felt on the dance floor, with the beat jumping or moving slow, walking down the street and being made to feel like the last star shining in bluest heaven, sitting on one side of the table at a restaurant where the meal was made even more delicious by what she was being told, living in the register of the voice on the other end of the telephone, standing next to him out on deck of the cruise ship moving around the island with the salt water air doing its best to make her hair nappy, turning into absolute fire and total delicacy when alone with him, and floating for days on the memory of one touch that went so much deeper than all the others.

In that orchestra, with that trumpet and the strings, on what midnight blue occasion has there ever been a better moment to open the barn door under the moonlight and let the songs go loose? The songs move not with fright but with ease. Those are the moments when feeling, above all else, has to show its face in sound. Such points of celestial clarity help the men among us get a better grip on where their strength actually comes from, and how it makes itself most felt.

Ardella’s man, Leroy Slocum, Jr., had been out there struggling in the wilderness. He was sitting in his room pretending all was well. On the street, when the memory arrived of the way she did what she did and went so effectively about being who she was, Leroy tried to play the memory off. At night, when a cluster of clouds might remind him of one of the ways she wore her hair, Leroy knew he had played himself, or that he had allowed himself to be played by listening when he should have gone deaf.

He got all tangled up in ideas about how he ought to be that had nothing to do with the freedom she gave him when the big feeling scooped the two of them up. He thought this and he thought some other stuff, usually at the advice of his strumble-brained friends, none of who knew anything about love but sure had plenty to say about it. They told the man that he was getting run around by this woman like she was his mother telling him chores to do. Didn’t he have no idea that when a woman starts to talking up all of your time that you had better watch yourself? You had better get your priorities straight. Get right and don’t be slow about it. Your first priority is being by yourself and going out to have whatever kind of fun you want to have whenever you feel it. That’s number one. Women always trying to pull somebody into something too close or too matrimonial so that they can drop that velvet-covered chain, drop that ball, trap these men out here. You got to know how to put all these things together. Back up some. Don’t be so available. Throw some space up in there. Give yourself some air. Guard that freedom. Put her in her place.

In that big feeling put under the tonal microscope of the trumpet and the strings, knowing how to be together is more important than knowing how to be alone, which is what all of us have to learn in order to become individuals of our own choice. When that time has been spent, however, when the woman is now woman and the man is now a man, and neither of them smudges like a bad copy of some other somebody, then the time to learn how to be together is more important than anything else. The trumpet and the strings give us the impression that there is no other subject worth comparing to the story of a man and a woman, because the great meaning of romance, the reason we all seek some version of it and the reason we all find ourselves coming back to it, is that romance says one thing more than anything else, and that thing is what we all want to believe more than anything else, no matter the subject, no matter the outcome: None of those profound feelings are meaningless.

In that winter, one day after a heavy drop the night before, when there was snow everywhere, Ardella turned a corner and saw Leroy coming in her direction. Each of them stood out against the whiteness that had covered the city and each of them appeared more individual than ever, walking in their overcoats, ears covered, and clouds coming from their mouths and their noses. They could have pretended that they didn’t see each other. They could have. There were plenty of wrong things that they might have done. But they didn’t. At that moment, it began as it had before they had parted. Life pleasantly mashed them up against each other.

In that union of the trumpet and the strings – when there is melodic surprise and the gentle or majestically searing rhythms talk of those periods during which all the gentle or majestically searing rhythms talk of those periods during which all the elements of life have slowed down and the good tone of the heartbeat rises through the flesh as an invisible presence of spirit, a romantic mist made perfect by intimacy – we are shown that romance, like breathing, is always a process of extension and return, letting out, taking in.

They didn’t have to fumble around with certain kinds of questions and an extended apology of one sort or another. They had paid that price when being alone made all of the troubles of the past less important because, even then, each of them knew that they had been together. She began to walk with him and he began to walk with her and she, who knew what had to be done to make all things clear, put her arm inside his. They were then a couple once more. With the snow blowing up a little so that tiny, tiny bits hit their faces and almost immediately melted, they both bowed their heads as if, while in motion, surrounded by so much that was cold, they were giving thanks to the fact that they were ready to lose themselves in each other’s arms once more, where the sweep of warmth would become, in all its simple surfaces, an intimate epic.

There, on that New York street, too happy to have decided on a direction, Ardella Jefferson and Leroy Slocum, Jr. were closely observed by the trumpet and the strings, the notes’ telescopes capable of seeing all that is outside in all places and all that is inside in any place. Doing their timeless job of speaking for all lovers, the brass horn and the strings realized that Ardella and Leroy were hoping to reenter that greatest of romantic myths, the one which has made the film, “Titanic”, so successful: If the big ship is going down and there is only one seat left on the last lifeboat, and the cold water and almost certain death closing in, the one who loves you will not get on. He or she will stand by your side and face whatever comes. And no matter what comes, there is no doubt in his mind, none in hers, that the passions of heat and tenderness that they have felt for each other, even in the face of terror and complete destruction, are not meaningless.

–Stanley Crouch

Credits

1. The Party’s Over (6:02)

B. Comden – A. Green -J. Styne

2. You’re Blasé (6:36)

P. Ord Hamilton – R. Bruce Siever

3. After You’ve Gone (5:43)

H. Creamer – T. Layton

4. Glad To Be Unhappy (7:44)

L. Hart – R. Rodgers

5. It Never Entered My Mind (6:04)

L. Hart – R. Rodgers

6. Baby, Won’t You Please Come Home (5:25)

C. Warfield – C. Williams

7. I Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out To Dry (5:55)

S. Cahn – J. Styne

8. I Got Lost In Her Arms (5:03)

I. Berlin

9. Ballad Of The Sad Young Men (5:47)

TJ. Wolf – F. Landesman

10. Spring Will Be A Little Late This Year (4:27)

F. Loesser

11. My Man’s Gone Now (4:32)

G. Gershwin – I. Cershwin – D. Heyward – D. Heyward

12. The Midnight Blues (11:53)

W. Marsalis

Wynton Marsalis — Trumpet

Eric Reed — Piano

Reginald Veal — Bass

Lewis Nash — Drums

Arranged and Conducted by Robert Freedman

Emile Charlap, Contractor

VIOLINS

Paul Peabody (Concert Master), Abe Appleman, Robert Chassau, Israel Chorberg, Krista Feeney, Narcisco Figueroa, Barry Finclair, Winterton Garvey, Kenneth Gordon, Richard Henrickson, Regis Inderio, Jean Ingraham, Ann Leathers, Nancy McAlhany, Ron Oakland, Susan Ornstein, Sandra Park, John Pintavalle, Matt Raidmondi, Laura J. Seaton, Richard Sortomme, Lisa Steinberg, Martin Stoner, Donna Tecco, Belinda Whitney-Barrel.

VIOLA

Lamar Alsop, Julien Barber, Lenny Davis, Karen Dryfus, Mary Helen Ewing, Carol Landon, Sue Pray, Maxine Roach.

CELLO

Richard Locker, Eric Friedlander, Eugene Moye, Clay Ruede, Mark Schuman, Fred Zlotkin.

BASS

John Beal, Lawrence Glazener, Paul Harris.

Produced by Steve Epstein

Engineered by Todd Whitelock

Assistant Engineer: Jen Wyler

Technical Supervisor: Mark Betts

Recorded Digitally at The Grande Lodge of the Masonic Hall, New York City, on September 15-18, 2007 and Mixed with 24-bit technology at Sony Music Studios, New York City.

The Management Ark

Santa Fe, NM • Princeton, NJ

Edward C. Arrendell II • Vernon M. Hammond III

Art Direction: Josephine DiDonato

Photography: Nana Watanabe

Personnel

- Eric Reed – piano

- Reginald Veal – bass

- Lewis Nash – drums

- Robert Freedman – conductor, arranger

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

The Midnight Blues - Wynton Marsalis Quintet at Paris Jazz Festival 2007

-

Videos

Videos

After You’ve Gone - Wynton Marsalis with the Toulouse Conservatory Orchestra at Jazz in Marciac 2005

-

Videos

Videos

Spring Will Be A Little Late This Year - Wynton Marsalis on Late Show with David Letterman

-

Videos

Videos

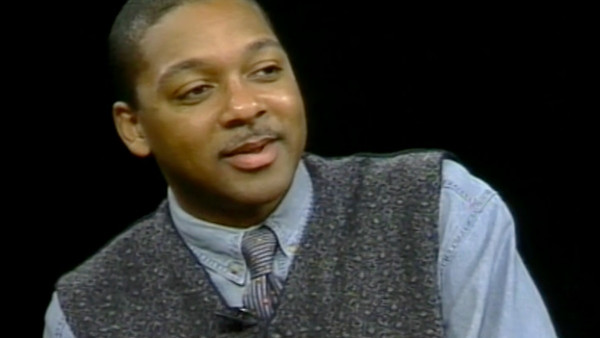

Wynton Marsalis on his latest album “The Midnight Blues” - Charlie Rose Show

-

News

News

Video: Wynton playing at Paris Jazz Festival 2007

-

News

News

Lincoln Center’s Man With the Trumpet, With Orchestra

-

News

News

Wynton playing in Marciac