A Heritage Is Affirmed In ‘Griot New York’

“Griot New York” is one of the happiest and most poetic dance premieres of the season. This first-time collaboration by the choreographer Garth Fagan, the composer and trumpeter Wynton Marsalis and the sculptor Martin Puryear is constantly blessed with a quality of surprise.

Free of polemics but rooted subtly in distilled allusions to the black experience, the choreography moves with urban bustle and pastoral lyricism toward a celebration of life. There is no griot, or African storyteller and keeper of his people’s history, onstage; but the collaborators play that role implicitly, offering a panorama of existence, a mini-epic of sorts.

Mr. Marsalis’s commissioned jazz score, superb in its evocative colors and original in its wit, had much to do with the success of this world premiere by members of Garth Fagan Dance on Wednesday night at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. “Griot New York,” the last entry in this year’s Next Wave festival, will be performed tonight and tomorrow night in the academy’s opera house (30 Lafayette Avenue at Ashland Place, Fort Greene).

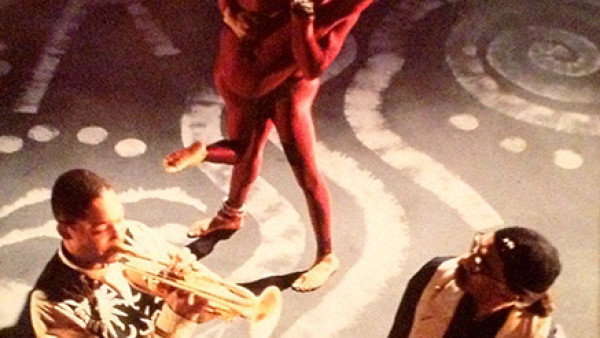

The Wynton Marsalis Septet, invisible for the most part in the darkened pit and then allowed an interlude of its own when the pit rises after intermission, envelops the house with an atmospheric energy, so much so that Mr. Fagan’s already energetic dancers seem virtually blown out of the wings by the music in their first entrance and consistently goaded by it.

Yet “New York Griot” is also the best choreography Mr. Fagan has created, a suite of ensemble dances or love duets of such natural purity that the audience is moved to roars, or simply moved. As for Mr. Puryear, every oversized artifact that he places on stage or suspends from above — from a clay jar to a huge hoe — immediately sets the tone for each section with its sophistication at the service of simplicity.

In recent years, Mr. Fagan has not always been as interesting as he could be. Starting out in 1970 in Rochester with dancers who had had no conventional dance training, he molded a vibrant troupe in choreography that owed little to anyone but himself. The current professional troupe, however, has sometimes had to fight against pieces that were too long, and sometimes against choreography that looked more awkward than assured.

Perhaps it is the music that makes the difference. Mr. Marsalis has stimulated Mr. Fagan into tighter patterns and structures, all the while allowing the offbeat shapes and partnering that are Fagan signatures to surface with witty freshness.

The eight subtitles of “Griot New York” suggest a concern with what the French call negritude: an affirmation of black heritage across the continents.

But Mr. Fagan’s choreography is abstract, devoid of literal ethnic connotations, and Mr. Marsalis and Mr. Puryear are definitely operating on a creative level that is anything but folkloric.

Mr. Puryear has the first word when the curtain rises and reveals his wonderful giant African water jar. It hangs upside down, a clay-colored object that alludes to historical roots but is also a contemporary work of art in its streamlined form.

Norwood Pennewell and Natalie Rogers, brilliantly sassy in her skirt with a silver lining (Mr. Puryear designed the costumes), shoot two arms up and lean out from opposite wings, retreat and then burst into the first section, “City Court Dance.” Eight others (Steve Humphrey, Valentina Alexander, Chris Morrison, Rebecca Gose, Sharon Skepple, Lavert Benefield, Bill Ferguson, Micha Willis, Bit Knighton and A. Roger Smith) join the pelvis-rocking prancing embroidered with high split jumps and kicks. The patterns, mainly diagonals suggestive of an urban grid, are geometric.

A blackout introduces a huge chain, allusive to slavery, on the floor. A man tries to rise to the virtuoso bass in the pit. Mr. Puryear comes up with a surprise, a fanciful hoe with a handle that arches like a tube in “Bayou Baroque,” with Miss Rogers leading the dancers (including Juel Bedford), some of whom strip down to black tank suits. Their partnering presages the coupling of “Spring Yaounde.” Miss Alexander perches on Mr. Pennewell’s side, and although locked in an angular acrobatic embrace, the dancers seem like children discovering that lips can meet if they face each other.

Mr. Marsalis and his musicians — Herbert Harris, Wes Anderson, Wycliffe Gordon, Farid Barron, Reginald Veal and Herlin Riley — have some terrific improvising-within-structures after “Sand Painting.” Mr. Smith lies down, initiating the death images of “Down Under.” A crippled-looking ensemble in tribal robes writhes at the foot of a mock staircase to paradise. A man slithers laterally with a body on his lap. Later the image is reversed with the same man in the arms of the one he cradled. But “Waltz Detente,” with its fox trots and polkas, “Oracabessa Sea” and “High Rise Riff” take the piece into another direction — the hope without which life is not worth living.

by Anna Kisselgoff

Source: The New York Times