Shock of the new

Wynton Marsalis is 10 minutes into an angry denunciation of hip-hop and he’s just hitting his stride. “I call it ‘ghetto minstrelsy’,” he says. “Old school minstrels used to say they were ‘real darkies from the real plantation’. Hip-hop substitutes the plantation for the streets. Now you have to say that you’re from the streets, you shot some brothers, you went to jail. Rappers have to display the correct pathology. Rap has become a safari for people who get their thrills from watching African-American people debase themselves, men dressing in gold, calling themselves stupid names like Ludacris or 50 Cent, spending money on expensive fluff, using language like ‘bitch’ and ‘ho’ and ‘nigger’.”

We shouldn’t be surprised that one of the world’s most famous jazz musicians is not a big hip-hop fan. The 46-year-old trumpeter and composer is regarded as a rather fogeyish, Brian Sewell figure in the jazz world, one who loudly registers his disgust at most music made since the early 60s. What is however surprising is that Marsalis’s latest album sees him trying to rap. The album’s final track, Where Y’All At?, is a state-of-the-union address, a declamatory, baritone-voiced sermon about a country in chaos, set against a jittery New Orleans funk beat. The lyrics make you cringe occasionally (“the rap game started out critiquing/ Now it’s all about killin’ and freakin’”), but it’s clearly a rap. Isn’t it?

“It’s rapping, but it ain’t hip-hop,” he says. “It’s the kind of rap we did in New Orleans back in the day. We called it juba juba, you know, ‘My grandma said to your grandma/ Iko iko uh nay.’ But it dates back long before the Dr John or Dixie Cups version of that song. Kids would sit on the street corner, improvising stupid rhymes with pornographic lyrics. You know the kind of thing: ‘Your old woman got an ass like a truck/ Your old woman she likes to fuck.’” He declaims the words while beating out a rhythm on the table. “Today’s hip-hop is just those pornographic rhymes on a grand scale.”

Aren’t you just using one strain of hip-hop to attack an entire genre? “Listen, I don’t have to attack hip-hop. Hip-hop attacks itself. It has no merit, rhythmically, musically, lyrically. What is there to discuss?”

Flow? Rhymes? Assonance? Scansion? Lyrical dexterity? Rhythmic complexity? The use of samples that explore African-American musical history?

“Yeah yeah,” he snorts. “It’s mostly sung in triplets. So what? And as for sampling, it just shows you that the drummer has been replaced by a loop. The drum – the central instrument in African-American music, the sound of freedom – has been replaced by a repetitive loop. What does that tell you about hip-hop’s respect for African-American tradition?”

Aren’t these the same objections that cultural conservatives made about jazz 70 or 80 years ago?

“How does objecting to hip-hop make me a conservative?” he yells, his gruff holler getting louder and angrier. “Is it OK to call me a nigger and your wife a bitch? If I object to that then I’m a conservative? That is ridiculous!”

One could drive a bus through some of the holes in Marsalis’s arguments. The man who rails against conspicuous consumption is the same Marsalis who advertises ultra-bling Movado wristwatches in the US; the man who denounces rappers for using made-up names seems to have forgotten those performers who called themselves Count, Duke, King and Jelly Roll. And since when have his assertions about drumming represented “the African-American tradition”? But it’s equally true that even fans of hip-hop will find a kernel of truth in what he says. “I’ve been arguing with [Public Enemy frontman] Chuck D about this, on and off, for more than 20 years,” he says. “Even he’s come round to a lot of what I’ve been saying.”

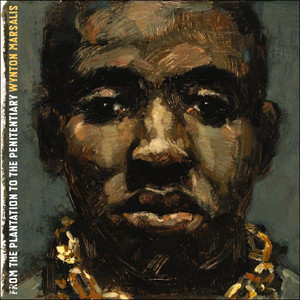

Marsalis’ fury is not confined to hip-hop. His new album, From the Plantation to the Penitentiary, is an angry, fascinating, exhausting and often infuriating polemic that addresses the legacy of slavery. It’s something that’s never been far from his work, but too often his grand compositions on the subject – such as 1994’s Pulitzer prize-winning opera Blood on the Fields, or 2001’s symphony for the New York Philharmonic, All Rise – have fallen short of his ambition. (The late New Yorker critic Whitney Balliett described Blood on the Fields as “suggesting a play about slavery written by a precocious eighth-grade class”.) Here, Marsalis takes the simpler form of a straight vocal jazz album, his quintet fronted by a 21-year-old from Florida called Jennifer Sanon, who was spotted singing Duke Ellington at a talent contest four years ago. Sanon delivers a set of didactic lyrics that examine the cracks in the American dream – rampant consumerism, the failure of public education, homelessness, government ineptitude, along with tirades against the misogyny of gangster rap – with a controlled anger that recalls the militant, civil rights-era jazz of Archie Shepp and Max Roach.

Marsalis is, of course, no stranger to outspokenness and controversy. For the past decade he has used his pulpit as the artistic director of jazz at the Lincoln Center – part of New York’s large and well-funded arts complex – to denounce his fellow musicians who have moved into funk, fusion and the avant garde. While he paints himself as a lone voice of dissent that needs to be heard (“There is a need for strong visions to be asserted so people can choose; mine is just a single vision”), he has a salary (revealed last year to be about $850,000), a budget and curatorial powers at the Lincoln Center that no other figure in jazz history has ever had. By concentrating on consolidation rather than experimentation (his jazz canon, broadly speaking, encompasses Louis Armstrong to early Miles Davis), he has been accused of encasing the music in aspic, and it has made him something of a hate figure in the faction-filled world of jazz.

There is no doubting his technique – Marsalis was a child prodigy who played Haydn’s trumpet concerto with the New Orleans Civic Orchestra at 14, and became the first person to win a Grammy in both the jazz and classical categories, aged only 22. But there are doubts about his legacy as a musician. He tends to use his technical virtuosity to stitch together pastiches of other trumpeters, such as Clark Terry, Roy Eldridge and Freddie Hubbard, while his compositions borrow heavily from Duke Ellington, Count Basie and George Gershwin. Many other jazz musicians have been highly critical. “I’ve never heard anything Wynton played sound like it meant anything at all,” said pianist Keith Jarrett. “He has no voice and no presence. His music sounds like a talented high-school trumpet player.” Trumpeter Lester Bowie agreed: “If you retread what’s gone before, even if it sounds like jazz, it could be anathema to the spirit of jazz.”

However, From the Plantation to the Penitentiary moves beyond Marsalis’s self-consciously traditionalist musical strictures into more contemporary territory. As well as the rap track that closes the album, there are songs that nod towards the spacey 70s funk recorded on the Strata East label and even the cryptic, angular, hip-hop-influenced rhythms of Brooklyn’s late 80s M-BASE collective – music that was always seen as the opposite of Marsalis’s defiantly retro brand of jazz.

“Every decade I try to do a record that has a kind of relationship to contemporary culture,” he says. “In the 80s I did Black Codes (From the Underground); in the 90s I did Blood on the Fields; now, in this decade, From the Plantation to the Penitentiary. As I say on the rap track, Where Y’All At, ‘You got to speak the language the people are speakin’/ ‘Specially when you see the havoc it’s wreakin’.’ Sometimes it’s important to speak in the vernacular, both lyrically and musically.”

The debris of Hurricane Katrina looms large over the album. Marsalis, a native of New Orleans, was one of the most prominent voices in the American media to denounce the government’s response to the disaster, and he held a large benefit at Lincoln Center to raise money for those affected by the floods. He sees Katrina as an event that reawakened a long-dormant political awareness in American culture.

“People looked at the TV set and saw central government – and, let’s not forget, local government, which was black – behaving with incompetence and inhumanity. We saw human beings suffering through bureaucratic fumbling, ignorance and stupidity. And we saw the descendants of slaves weeping in front of the cameras, saying, ‘Have you seen my family? Have you seen my friend?’ And that was eerie. That could have been happening in 1840, do you know what I mean? It made you realise that the legacy of slavery is very much with us. And I think that radicalised a lot of people. It’s become something that’s forced Americans to ask serious questions about what we are doing. I would hope that people are more receptive to these ideas than they’ve ever been.”

· From the Plantation to the Penitentiary is released on Monday on Parlophone

– by John Lewis

Source: The Guardian

Comments

Please send me the Gurdian Unlimited

Ian Christner on Mar 13th, 2007 at 3:12pm

I love your new album.

Emily Delahoussaye Thomas on Mar 10th, 2007 at 12:33am

;)

Luigi on Mar 2nd, 2007 at 9:52am

This recording is already creating a stir and it has not yet been officially released. It’ll be a lively Spring around here!

gloria on Mar 2nd, 2007 at 9:18am