Wynton Marsalis & The Glories of Jazz

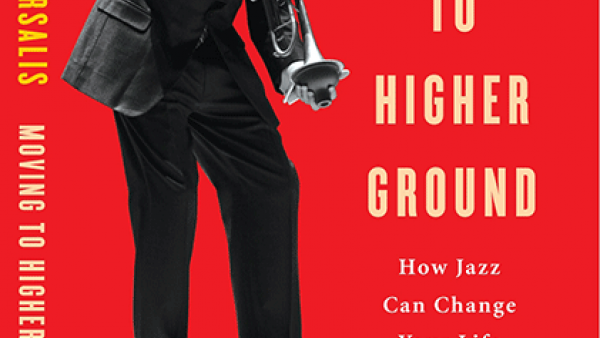

In his new book, “Moving to Higher Ground: How Jazz Can Change Your Life,” Wynton Marsalis celebrates his passion. This generation’s global jazz emissary explains how a life lived under the spell of swing rhythm and imagination helps the body, mind and spirit soar.

After a full morning last month, the jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis took a brief respite. He had just composed parts of a symphonic piece for the Michigan State and Detroit Symphony orchestras.

Then he sat for a broadcast interview that ran well over schedule. To unwind while walking to his next interview through Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City, where he is artistic director, Marsalis began scat singing, replicating improvised horn playing. In his dressing lounge, Marsalis loosened up for a few minutes by playing a blues shuffle at the piano.

That Marsalis, 46, chooses the language of jazz to unwind and renew his energy should come as no surprise. The most public face of this uniquely American creation, Marsalis has presided over Jazz at Lincoln Center and its orchestra for the past 20 years. He is an emissary for the music, whether he’s hosting children and teens in seminars and band competitions or speaking before business groups about jazz and value creation.

Jazz, Marsalis contends, exemplifies human relations, personal and political freedom, and good health. He makes the case in Moving to Higher Ground: How Jazz Can Change Your Life (Random House), which hit bookstores last month. A jazz solo, for example, is a declaration that “I am.” And riffing—repeating a musical phrase—has the universal familiarity of a parent encouraging her children: Sit up straight. Sit up straight. Sit up straight. “Good riffs are always compact, meaningful, well-balanced and catchy,” Marsalis writes in Higher Ground. “They can show us how to speak succinctly, get to the point, and stay there.”

Marsalis has long likened jazz to democracy; the music encourages the expression of personality and individuality while teaching one how to listen to others. Blues—the roots of jazz—improves physical health by working first on the mind, like psychological counseling or complementary therapies. The blues, Marsalis tells Energy Times, “is optimism.”

Blues is the underpinning of Marsalis’ collaborations with Bob Dylan, the Allman Brothers and others from diverse musical worlds. His latest album, “Two Men with the Blues” (Blue Note), with Willie Nelson, was recorded live at Jazz at Lincoln Center last year. It presents Marsalis and the country star trading guitar licks and trumpet solos, and sometimes vocals, on “Basin Street Blues,” “Caldonia” and standards like “Stardust” and “Night Life.”

A nine-time Grammy winner, Marsalis has won the award in both jazz and classical categories. He is the only jazz musician to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music, for his epic oratorio Blood on the Fields. But Marsalis’ popularity in his native New Orleans has less to do with his awards than with the leadership role of the trumpet in New Orleans bands and his part among the long lineage of larger-than-life trumpet players from the Crescent City, from Buddy Bolden to Louis Armstrong.

“In New Orleans, people love Wynton Marsalis like they love Louis Armstrong,” says trumpeter and bandleader Irvin Mayfield, a Marsalis protégé. “People see him as a continuation of what Louis Armstrong has done. People in New Orleans love their trumpet players. When they celebrate, the trumpet is the important thing and you’re a part of that.”

In his Jazz at Lincoln Center dressing lounge, beneath black-and-white photos of Armstrong and other jazz trumpet players like Clark Terry, Harry James and Miles Davis who have helped pave his path, Marsalis spoke with Energy Times about how music and especially jazz can enhance personal and collective health.Energy Times: In Moving to Higher Ground, you make a strong case for how jazz can improve our relationships and contribute to our well-being. Why does jazz and, in particular, the blues, which is about sad circumstances, make us feel so good?

Wynton Marsalis: Your mental state affects your physical health. The blues is optimism, and optimism is not naïve. That means you can absorb tragedy. When you have something very painful, something you don’t want to deal with, the blues helps you confront it.

But because the blues is grooving, it gives you a release for it. That’s the optimistic part, and dancing also helps. If you dance your vitality will go up. Dizzy Gillespie used to say, “Dancing never made nobody cry.” It’s important to cry and it’s important to celebrate, and you have to make your life a celebration. Blues helps you come to grips with tragedy and with pain. That’s the power of somebody like Billie Holiday or Miles Davis.

The blues contextualizes pain. It says “my man left me,” but underneath that the music is happy. Some blues is slow, but the rhythm and the groove always put joy in it. Even with the saddest feeling in the world, they can put a rhythm on it.

Music is the art of the invisible. And it reigns over all the invisible things like thoughts, imagination and feelings. Music can do a lot to help the development of our internal life. That’s really the ultimate power of music and that’s what gives certain musicians greater depth than others because we’re all using the same notes. But there’s something in the music of Beethoven, the way the notes are organized, there’s something in the sound of Louis Armstrong that will heal you. And for some reason a lot of jazz musicians are perpetually young and youthful. Those who didn’t succumb [to drugs] remained very youthful deep into old age. A guy like John Lewis [pianist and composer with the Modern Jazz Quartet] is a good example. [Jazz drummer] Elvin Jones. They’re playful. You’ll be in a room with musicians in their 70s and they’re like kids. They came from the Great Depression.

They were very communal. Musicians that were 15 years younger than them came up in a different time and were much more combative. Music was less communal for them, and they don’t have the same youthfulness.

ET: One of the great strengths of music, certainly in music therapy, is that a single song can mean so many different things at once. That appears true of the blues as well. Alan Turry, a therapist at Nordoff-Robbins, told me the blues resonates because it integrates the sacred and the sensual, that it has life-affirming energy.

WM: That’s right (sits at the piano and plays the two chords played in church behind “Amen”). You’ve heard this in church. It’s called the Amen cadence. It’s the fourth degree of the scale onto the first degree of the scale (plays a few blues measures, singing “A-men” to demonstrate how the cadence fits).

In Western music there are major modes and minor modes. Minor modes are said to be sad and major tend to be happy. The blues puts both together. It’s also in Eastern music, the pentatonic scale. The music also has a shuffle rhythm (humming), and that’s a combination of a waltz and a march. The blues has a lot of fundamental music relationships from all around the world encoded in its DNA. That’s why it’s universal.

ET: So it’s a mix of sorrow and joy—the conflict and the resolution.

WM: Right. Even real sad blues: “10,000 people standing around the burial ground/When they laid my baby there I was not around; 10,000 people standing around the burial ground/When they laid my baby there not a one made a sound.” Then at the end it’s redeemed. “There’s 10,000 people standing around the burial ground/Never knew how much I loved her ’til they laid her six feet down.”

Mighty sad, but it’s happy. It’s like a bitter happiness because he found his love, but she’s dead. That’s the blues. Anyway you look at it, it’s bitter but there’s something else in it.

ET: In your book, you write about “the creative tension between the self-expression and self-sacrifice of jazz.” You say that tension is “at the heart of swinging in music and life.”

WM: It’s just the basic dynamic of living with people. Jazz is about that because we make the music up together. If I play a piece of classical music, even a difficult piece, I am communicating the wishes of the composer through my instrument to the audience. There’s some way I can put some more personality into it, but the personality of the composer will predominate.

With a jazz performer, the people who are playing are all making up something. So they create the music and what they have to say is important. In big bands sometimes you only have parts, but you get to solo and you get to set riffs. You have a lot of little things you can do that can affect the creation of the music. That’s why in jazz, more than other art forms, you are forced to respect the position of the other person, even if you don’t want to.

I’m the leader of the band, but I can’t determine what the drummer will play when I’m playing. I can’t tell the bass player what notes to choose. I can’t tell the piano when to come in. They’re going to make those decisions, and if I want to be successful in my solo I will have to go with it. There’s no way they will play exactly what I will want to have played. That’s not possible. But I better figure out how they can play with me. You have to give them space. There are a lot of things you have to do to have a rhythm section want to play with you.

ET: Rock and roll is replete with long improvisational jams in which musicians are communicating with each other. Can’t that teach the same lesson?

WM: Rock ’n roll is loud. When music is loud it is impossible to communicate a lot of the nuance and essence of it. The other thing is that the drum beat slaps on two and four on every song throughout the entire song. That’s the greatest deterrent to improvisation. The drummer has to do that, so you have got to play in relation to that. The drums are enslaved. The heart of the music of jazz is drums. We have a rhythm, a swing rhythm. Once the drum becomes something a machine can play, it’s another style of music.

ET: You write about time and its importance not only in jazz, but in life. You say a musician’s relationship to time can shed light on how and when to expend energy, or master moments of crisis.

WM: In the moment of a crisis what do you think about? On the bandstand a lot of times a musician would start to analyze what’s wrong. You can feel it, because the time is passing. You don’t have the time to analyze what’s wrong. The only thing you have time to do is correct the next moments of music, so your thought process has got to be, “What am I trying to do with my solo and where can I go with my reflexes to redeem this situation?” And you hope all the other musicians are doing that. If all the other musicians assume they’re at fault and don’t spend time concentrating about who’s off you will come back together; if not you will fall apart.

Focus on the objective at hand. For instance you found out your old lady cheated on you, and you’ve been married 15 years. You’re betrayed, you’re angry. What are you going to do, as opposed to “how can she do this to me?” One way of thinking is putting all the focus on what has happened to you. Another is to look at what is going on in the holistic sense, and what you are going to do to make this situation better.

ET: Much of what you have been discussing about applying the principles of music to your life relate to playing. How does someone apply these principles as a listener?

WM: Listening to music is just like listening to words. You develop a vocabulary and an understanding through doing it. And you get to the riches by listening and knowing what to listen for—what instruments to hear, what solo is coming up, where breaks are, how they develop material. A lot of music is available. It’s a matter of choice. It’s like people with TV; there’s a lot on TV, just turn on another channel.

ET: You rail against the importance placed on charisma and personality over music today. You’ve also been criticized for your traditional definition of jazz.

WM: I believe the essence of jazz is the swing rhythm and the blues. I believe there are many forms of music outside of jazz that are considered jazz. Doesn’t mean they aren’t good forms, or that the music is not good music; it’s just a descriptive thing.

I believe the direction that popular music has taken is regressive, from high levels of musicianship to non-musicians in 60 years. That’s not an achievement. It’s like if you went to amateur doctors.

Let’s talk about public dance. Public dance is the vitality of the people. Every country that has produced an art form that combines European and African music has a dance tradition that all the people in their cultures still dance: Brazilian people with samba, Argentinean people with tango. In Cuba, old and young dance together. Where do you see that in America, except sometimes at wedding receptions? What happened to the vitality of our national dance? Generations are so separated, and the most important thing for young people are the rituals of courtship. Why would something that central be something no older people are a part of? We have to think about that.

ET: What is the healing power of the trumpet?

**

WM: The trumpet can bring down the walls of Jericho. It’s an instrument of announcement, proclamation. You take the natural element metal and you humanize it. You speak through the voice, through the vibrations. So from that tiny sound, that vibration, the trumpet is a megaphone, it magnifies, it’s an attention grabber. The trumpet delivers the message and it let’s you know what the state of affairs are.

In terms of how sounds affect your health, what is in a sound is the same as what’s in a thought. A thought has power. The thought that you send my way can heal me or make me sick. To be in a house with a lot of negative thinking, even with no talking, will affect your health because we live in a holistic environment, and in that environment, it’s all vibrations, it’s all connected. That’s what you learn from music. If I play a C and a C sharp, harmonically they are the furthest apart; spatially they are the closest.

ET: Proper breathing is important no matter what instrument you play, but it’s got to be particularly important to a trumpeter. What do you do to ensure strong respiratory health?

WM: You hold the note for a long time. You take a deep breath and you try to hold the note for one minute. You try to get the biggest sound with the softest volume. It’s all opposites. It’s a sound that’s very open with the softest volume, like an ohm.

ET: It’s meditative.

WM: That’s what it is. It is a meditation because you concentrate on the core of that sound and opening the sound up without the volume opening up. Putting in the core of that sound, the positive attributes and the most love—concentrating on that is healing.

by Allan Richter

Source: Energy Times