Interview: From Marsalis, Jazz Profiles in Verse for Kids

From NPR News, this is ALL THINGS CONSIDERED. I’m Michele Norris.

(Soundbite of trumpet music)

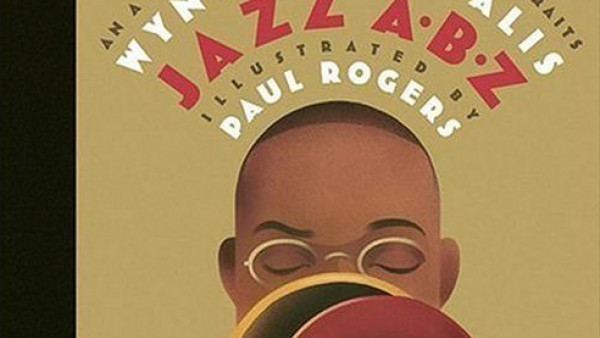

NORRIS: Wynton Marsalis has put down his horn and picked up his pen for his latest project. It’s a book called Jazz ABZ, and in it Marsalis shares his deep knowledge of jazz in all its forms with children. Marsalis jitterbugs his way through the alphabet profiling 26 jazz legends through a variety of poetic forms. Marsalis worked with illustrator Paul Rodgers. He created individual portraits reminiscent of the old posters that adorned vintage jazz joints. He sent those pictures to Marsalis and he first considered writing poems and music for each portrait, but the thought of writing music for these jazz legends just didn’t seem right. So he stuck with poetry.

Mr. WYNTON MARSALIS (Trumpeter): I came upon the idea of writing a different type of poetic form for each letter, and then I started writing the poems, you know, on the road and reading it to cats, ‘cause we drive everywhere, and it just developed that way.

NORRIS: Tell me about the process. You’d listen to music and then you’d decide which poetic form you’d use for each musician.

Mr. MARSALIS: Well, I didn’t have to listen to them; I mean, I know most of their styles, so I didn’t actually listen to their music. But I decided, like, Louis Armstrong’s poem is what’s called an accumulative poem. It’s because he’s the accumulation of all of what’s in our music and he’s A, so he’s the beginning.

AMANDA FERNANDEZ (Duke Ellington School for the Arts): “Armstrong.” Armstrong almighty…

(Soundbite of music)

FERNANDEZ: …an ad-libbing acrobat. American ambassador of affirmation. Adventurous author of ambrosial airs. Absolute architect of the jazz age.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. MARSALIS: Count Basie is the blues, ‘cause that was his form that he loved.

(Soundbite of music)

FERNANDEZ: “Bouncing with My Baby to Basie’s Big-time Band.”(ph) Bouncing with my baby to Basie’s big-time band, rhythm is their business. But the blues is their brand. Up from Kansas City with a button-down 4/4 swing…

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. MARSALIS: Duke Ellington I use meter play because he wrote so many different styles. For Lester Young I used a Japanese form called tanka because he has a kind of real spare style. For Monk a haiku just because—I mean, Monk’s style is very simple and bare but essential. For Bix Beiderbecke a ballad, a kind of English ballad because he has such a kind of sweet lyric and tragic story.

RANDOLPH JACKSON ALVARENGA(ph) (Duke Ellington School for the Arts): He exults in lyric sweetness, excites on zesty jumps, exhibits exclusive features, exudes that umpty-ump.

(Soundbite of music)

ALVARENGA: He travels on extensively, exports the jazz solo. His records are exemplary, but whiskey lays him low. Exhausted he goes home to fix what tattered soul he has. His folks reject his life’s love. Bix—he exits blowing jazz.

(Soundbite of music)

NORRIS: Is—this is a children’s book, so ideally parents are going to sit at their bedside and read this book to children. I did this with my children, and it is challenging.

Mr. MARSALIS: Right. Well, I wanted to make it be a children’s book with real big words in it.

NORRIS: Real big words.

Mr. MARSALIS: Because, you know, I always…

NORRIS: It requires a certain lingual dexterity to get through this.

Mr. MARSALIS: Well, you know, it’s from having my own kids. I used to love to read stories to them, and they would always say, `No, no, tell us the story with your mouth.’ Like they wouldn’t want me to read it; they’d want me to make it up. But I always loved to hear them use big words for them, like, you know, protect is `retect’ and the computer’s `temputer.’ I just—I like to hear little kids when they speak words and they don’t know what they mean. So I thought it would be great to write a book just full of big words for kids that are like four and five years old. They don’t have any idea of most of what we’re talking about.

NORRIS: But they can infer a certain meaning just by hearing…

Mr. MARSALIS: Right. They pick up…

NORRIS: …the way that you say something, the…

Mr. MARSALIS: Right. That’s what we call the underneath language. It’s like that’s what music is. And I think we learn language through the music of the language.

JESSICA DOBIE(ph) (Duke Ellington School for the Arts): “Coltrane.” Country is corn bread, collard greens, fried chicken, cane and even chitlins is celebrated in the big city of upcoming champion of scales, clefs and cutting-edge concept.

(Soundbite of music)

DOBIE: Couldn’t he capsize calcified conventions and challenge the contrarian campus critics? But couldn’t he create controversy amongst the condescending cognoscenti?

NORRIS: Billie Holiday—first name begins with a B, last name begins with an H, but she represents the letter L, and the picture that accompanies that poem could, I guess, be described as languid?

Mr. MARSALIS: I guess you could say that. It’s her singing as this kind of poster—a lot of times Paul is bringing in forms that existed in different times, like the way we have the posters with the stars on it and this person is appearing here. And I love the background, in blue, cats playing, like the implication is that it’s at night with the stars and stuff, and she loves Lester Young, of course; he has the saxophone. He has Lester Young in it with his porkpie hat playing the tenor saxophone, and he gave her the nickname Lady Day.

HILLARY EDWARDS (Duke Ellington School for the Arts): Should I laud my lady with gold-leaf clusters, with a lavaliere of lapis lazuli or lotus and lilac poems? Well, let me applaud my Lady Day in song.

(Soundbite of song)

Ms. BILLIE HOLIDAY: (Singing) Empty pockets don’t ever make the grade. Mama may have, hot fun they have, but God bless the child that’s got his own, that’s got his own.

EDWARDS: Always will I love you and love to always love you.

Mr. MARSALIS: That’s one of those kind of lines where you can turn the letters around and turn the feel around. I’m going to love you forever and I’m going to love to be loving you forever. So kind of double meaning of a turned phrase.

NORRIS: There is a lot of wordplay in here; there’s a lot of alliteration. As I was reading this I wonder if it was the thing you might hear, and I mean no disrespect in saying this, the kind of thing that you might hear on a playground, for instance.

Mr. MARSALIS: Well, I want it to have that kind of playful quality, and even at my age I still play and have, like, a lot of childish—and I think a lot of musicians are like that. They like to play around and joke and clown. Well, I think artists in general. So it really was like a labor of love for me in play, and I also wanted to tease Paul and mess with him, you know, ‘cause I was writing it with him, and, man, check this out. A lot of times with musicians—we joke around with each other and we show off for each other. You know, we compete with each other, but it’s in fun.

NORRIS: Wynton Marsalis, it’s been great talking to you. Thanks for coming in.

Mr. MARSALIS: Thank you.

NORRIS: Wynton Marsalis. His children’s book is called “Jazz A-B-Z: An A to Z Collection of Jazz Portraits.” Thanks to students from the Duke Ellington School for the Arts in Washington, DC. They came to our studio to read from the book. You heard Amanda Fernandez, Randolph Jackson Alvarenga, Jessica Dobie and Hillary Edwards. More of Wynton Marsalis’ jazz poems and illustrations from “Jazz A-B-Z” are at our Web site, npr.org.

(Soundbite of music)

NORRIS: You’re listening to ALL THINGS CONSIDERED from NPR News.

by Michele Norris

Source: NPR