Wynton Marsalis Reflects on 30 Years of Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra operating under the leadership of New Orleans trumpet great Wynton Marsalis, who co-founded the program in 1987 (the Orchestra was started the following year) and serves as both its managing and artistic director. And during that time, the JLCO has established a body of work that’s explored some of the deepest aspects of American history, from the country’s oldest Baptist church to New Orleans’ Congo Square to the roots of the nation’s most beloved children’s songs.

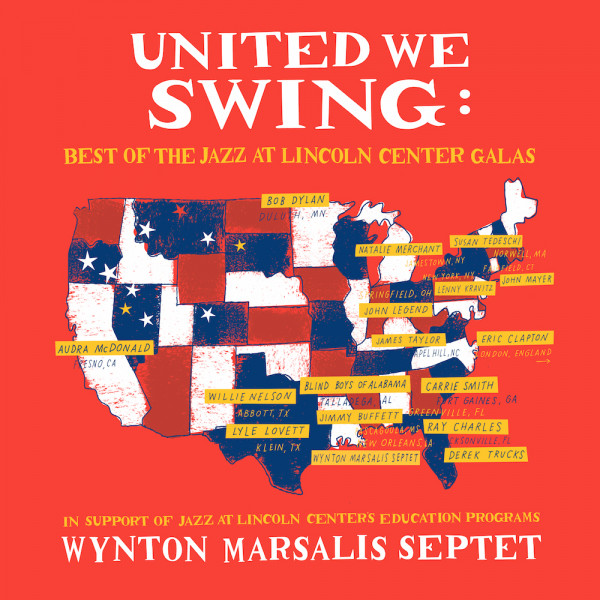

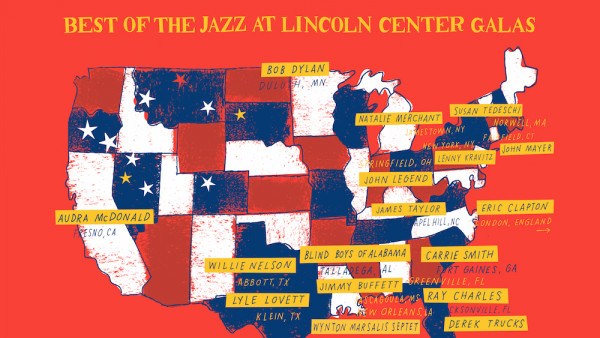

Between 2003 and 2007, Marsalis and his legendary septet hosted some of the biggest names in pop, rock, blues, country and R&B at the Jazz at Lincoln Center Spring Galas. Within that five-year stretch, the Wynton Septet jammed with an unparalleled cast of talent that included such names as Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Willie Nelson, Natalie Merchant, Lyle Lovett, John Legend, James Taylor, Lenny Kravitz, Susan Tedeschi and Derek Trucks and, in one of his final appearances onstage, the late Ray Charles.

United We Swing collects the cream of these gala performances for an album whose proceeds are going to Jazz at Lincoln Center’s much-needed educational programs. And much like his work with the JLCO, these songs — when sequenced together across this 16-track collection — tells the crucial American tale of the union between jazz and the blues, and the way by which both genres have served as spiritual turbines propelling the people’s history of this country through the generations. Marsalis took the time to speak with Billboard about releasing an album like United We Swing in a time when our nation has never felt more divided.

You recently played a concert at Jazz at Lincoln Center that revolved around classic nursery rhymes and children’s songs, which have historically been on the frontlines of the American protest movement when the music of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger began getting integrated into children’s education curriculum. Was that where you were coming from in the context of these arrangements?

Yeah. I love folk music, which I call American root music. Root music is very crucial. It’s important to jazz, important to improvisation. It’s important for so many reasons. It’s hard to have improvisers in a certain style if they don’t know root music or if they don’t have a relationship to root music. That’s one of my big things and I have a real belief in that. I’m always insisting with my students of the importance of that style of music. The real folk music, it comes from the soul, from the people. In New Orleans, we have a lot of root music that’s a deep part of our culture. And when you’re growing up, you take it for granted. But as you get older, you begin to understand the importance of that church music, the hymns and things like that.

The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra under your direction turns 30 this year. Did you have a template for how you wanted to lead this band when you first stepped into the position?

Duke Ellington’s band: our founding members included folks who were in their twenties and early thirties from my generation, members of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra who were in their forties and fifties and members of the Duke Ellington Orchestra who were in their sixties and early seventies. But it was that Ellingtonian way which was at the root of what they did. I didn’t grow up listening to Duke Ellington’s music. When I came to New York, I started to meet all the heavyweights like Ralph Ellison, Arthur Miller, Stanley Crouch and that group of intellectuals, and they were all listening to Duke. Me being a product of urban education, even with my father being a jazz musician himself, I didn’t really know what that tradition was. I remember not wanting to play in a big band. But then I talked to Dizzy Gillespie and he told me, and I’ll never forget what he said, “You have to remember: To lose one’s orchestral conditioning should not be considered an achievement.” And he told me to get that big band and keep it together. But then we started to establish our own traditions from the Ellington traditions. And by the time you hear it now, we have ten arrangers and we have a whole canon of music we’ve created ourselves. We are all working on music all the time and we are always writing.

It’s quite interesting to see an album out there like United We Swing in a time when patriotism has been such a weaponized word in the hands of the right wing establishment in this country. What do you think of the word patriotism in 2018?

I know what you’re saying, but we don’t actually recognize it. I don’t look at it like these are the wings or whatever. You gotta get Ralph Ellison’s book Invisible Man. If you read that book, there’s a lot on it about the kinda everyman. Anytime there’s group thinking, be it an institution or a group, it’s doing something to you. It’s the allegiance to groups that he goes through in the book, and groups that are opposite. Every time you encounter this type of mass thinking, this brainwashing in adapting these philosophies like blaming Washington, it actually doesn’t have anything to do with your real experience. It kinda forces you into a position that’s right or left, but that’s not what you’re living in. My theory about patriotism is this: I live in this country. I believe in the truth of democracy. But the truth of it is you have to figure out how to construct your life from a reality with which you are familiar, not some philosophical concept you don’t live. Willie Nelson is patriotic. Ray Charles was patriotic. They both believe in America, but that doesn’t mean that they believed that the minimum wage shouldn’t be raised or that people should be replaced at their jobs by robots. People who are debating the issues and feel strongly about either side can also be patriotic. I agree with you that lately there seems to be only one definition of patriotism. But in fact, there are many definitions.

How far do you go back with Ray Charles?

My little brother played with Ray, but I didn’t really know him until he came and did the show. Most of the artists who came to play at these galas I didn’t really know, but we had a lot of really interesting connections. Like, for instance, Lyle Lovett’s bus driver was a friend of our bus driver. And our bus driver, Harold Russell, we love him like family and we were on the road all the time, and he would always talk about Lyle and how much he loved Lyle. “Man, that’s a good guy,” he used to say. “That was my man!” So when I called Lyle, we talked all about Harold Russell (laughs). And with Jimmy Buffett, it was because he’s associated with the Gulf region and New Orleans, so we had that Louisiana connection.

One of the things that makes United We Swing so special, in fact, is hearing the likes of a Jimmy Buffett or a James Taylor in a jazz light…

The proof of all of it, just in the rehearsals, exists in the type of love that everyone showed for the music and the seriousness that was exhibited. Everybody was for real, man. For Eric Clapton, it wasn’t just about the songs that he loved; it was about the music itself. Everybody was curious about it, and they wanted to play in the feeling of jazz. We’d have a little party at my house afterward, and everybody was very cool. And everybody donated their time and energy for our education programs, which we have 12 of them now. This year alone, we’re gonna have 3 million people view our Jazz Academy website and interface with our faculty. There’s a free competition for high school bands called Essentially Ellington and a summer camp coming up. We’ve had so many things that were enabled by musicians.

It’s great to hear, because it seems like the future funding for music education is going to be saddled solely by the public and musicians such as yourself if this current administration has its way about cutting PBS and the NEA from the budget. It always seems like federal funding for the arts is always on the chopping block, right?

Yes, and that’s because of ignorance and lack of understanding. They value the arts as a commercial product, not as something crucial to the importance of our mythology. But again, I don’t think so much in terms of Democrat or Republican when it comes to the arts. It comes down to the person. And if you look at the funding for the NEA over the last 20 years or 25 years, it’s not necessarily like a Democrat comes in and there’s a big $300 million windfall for the arts. Someone like Willie Nelson if you look at all the stuff he does with Farm Aid and all his charities. He’s always doing something for people. You have to love him if you know him. When I heard about him and Ray Charles talking about 1961 when they first met, that was unbelievable. They loved each other and had a long-term relationship as friends and colleagues.

Even though they played different forms of music, they really were kindred spirits, Willie Nelson and Ray Charles, huh? The soul they projected in their music, I’m talking about.

Hey, if you think about Willie Nelson, Ray Charles and Louis Armstrong, the three of them have something in common, which is that all three of them are credible in the blues, they could swing the gospel tradition, they can sing from the Great American Songbook, they can play jazz and improvise incredibly and they can sing country songs. It’s incredible.

One of the highlights of United We Swing is your version of Bob Dylan’s “It Takes A lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.” What inspired you to choose that song from his catalog?

He chose the song first, because it was American mythology. Trains, you know?

Do you think Dylan’s music lends itself well to jazz?

All the music that has blues in it is related to jazz. When somebody is singing “I ride on a mail train,” that’s the blues. “Don’t the moon look lonesome, shining through the trees.” That’s Count Basie and Jimmy Rushing from 1938. That’s blues mythology. That’s what it is. Blues is the root of everything. But once jazz put a rhythm section together, everything that has a rhythm section on it comes out of jazz. And the artists we played with on this album recognized that, which is why there wasn’t a problem. I enjoyed arranging these songs.

You can definitely hear that in the version of Lenny Kravitz’s “Are You Gonna Go My Way?” on United We Swing, for sure.

I was coming from a New Orleans vibe with a Coltrane-esque feeling and the kind of apocalyptic thing that Lenny was talking about. It’s also good to have Herlin Riley and the New Orleans rhythm section, because they can translate all these rhythms into a certain thing that relates to jazz; because in New Orleans, we play a lot of different styles of American music.

Another genre that has been entangled in jazz over the last 25 years or so has been hip-hop, which currently through the likes of Chance the Rapper and Kendrick Lamar is bringing young people back into listening to jazz. Do you see that?

Well for me, especially back in the ’80s, what I represented being a black guy who was serious and young and not wanting to be a part of the whole gangsta/pimp mentality, and that caused a lot of problems for people. And it was because for those people, they wanted the mythology that they had grown up with. Again, I think a lot of it is in the Ralph Ellison book Invisible Man. I didn’t want to be equated with all these things that had nothing to do with me. Part of the whole thing is to create a fake identity of something and attack that. The things they were willing to craft were not based in reality, and they didn’t drag me in because I didn’t want to go along with it and capitulate to their view of the world where they put the Negro second or third, or fifth. It was a problem. But again, that was a ’80s thing. Now that I’m 56, a lot of those people are not even in the music business anymore. Those positions have shifted. Now, it’s not so much of a problem, because what they were trying to do back then has been done. Are we still gonna acknowledge that we have people calling themselves n—-as and bitches and hoes, and they got the certain level of absurdity that they wanted. What else did they want to do?

The #MeToo and Time’s Up movements seem to be killing off some of the “bitches and hoes” talk.

Well, I hope you’re right, because I don’t see it yet. Why? I don’t know why. But speaking for myself, I was always against that. And back then, I was seen as conservative. If that’s what it is, then so be it. I don’t wanna call people bitches on a record. And if I am conservative because of that, so be it. I don’t want to be called a n—-a on a record. If you wanna use the word n—-a and say it along with all this other shit you feel like saying, then great. It’s like what my mama thought about the movies that were being made to celebrate a pimp. She didn’t think shit about it, but we loved it.

What do you think about what Ice Cube said about the N-word on Real Time With Bill Maher, where he said that African-Americans use it as a means of claiming the word as their own?

I don’t agree with that. I don’t care what anybody says. It’s a 19th century pejorative term. It’s not a default cultural position. And for some reason, it’s met with this great national celebration. Then why are you black, then? It means the same as it did in the 19th century. This is not the first time a predominantly popular music used the word “n—-er” all the time. There was a good seven, eight years of that with the minstrel shows. I’m from the Civil Rights Movement era. I don’t believe in that. I don’t want it as part of our mythology. It’s not a default position. It’s not a mainstream cultural position. And neither is bitch, and neither is ho. You don’t wanna raise your kids with that as the default position in America.

by Ron Hart

Source: Billboard