Wynton Marsalis: Jazz king of the jungle

In 1979, trumpeter Wynton Marsalis arrived in New York from his home town New Orleans to study at the Juilliard School. Since then his career achievements are legion: prolific recordings, several Grammys, successful international tours, a major influence as an educator and a reputation as one of the finest living jazz musicians.

His greatest achievement, however, was co-founding the jazz program at New York’s Lincoln Centre in 1987. That event has led to unprecedented influence, not only for himself as a performer, but also for the convictions that have inspired him for 40 years: a vision of what jazz is. Or, for that matter, what jazz is not.

In 1988, the 15-piece Jazz at Lincoln Centre Orchestra became resident at the centre. But it wasn’t until 1996 that Marsalis’s project was solidified. In that year JALC became independent, and bought its own building in Columbus Circle. Simultaneously it was installed as a new constituent of the Lincoln Centre, and given equal parity with the New York Philharmonic, Metropolitan Opera and New York City Ballet.

Jazz, now regarded as “America’s music”, had finally arrived. It had become part of the cultural establishment.

“I felt it was a sign of maturation for Jazz at Lincoln Centre as an institution and also for Lincoln Centre for the Performing Arts”, Marsalis tells Review. “We had all worked towards that goal and there was a sense of achievement for the art, the arts, our New York community, and for the country.”

Since then, JALC has enhanced its prestige. In 2004 its Frederick P. Rose Hall, the world’s first performance, education and broadcast facility devoted to jazz, was opened.

Investment broker Robert J Appel became chairman of the JALC board in 2012. In 2014, he gifted $US20 million to JALC, the largest philanthropic contribution in support of jazz in US history.

Marsalis’s vision for jazz is now manifest. The principles he has long stood for appear in JALC’s mission statement: “We believe jazz is a metaphor for democracy. Because jazz is improvisational, it celebrates personal freedom and encourages individual expression. Because jazz is swinging, it dedicates that freedom to finding and maintaining common ground with others. Because jazz is rooted in the blues, it inspires us to face adversity with persistent optimism.”

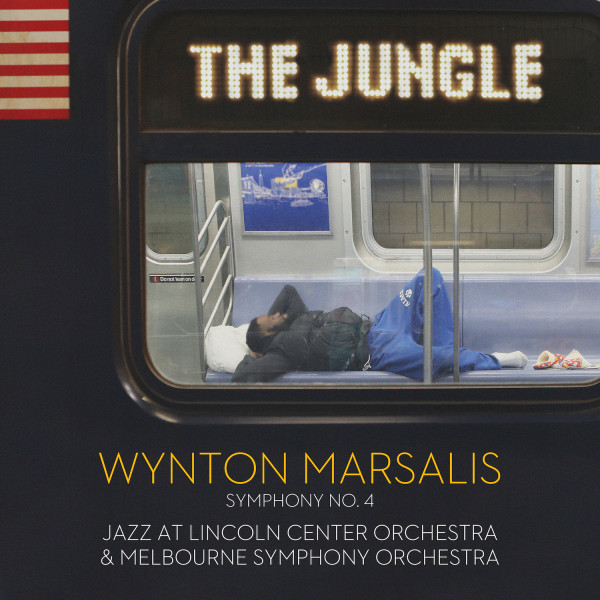

Marsalis will be touring Australia this month with the Jazz at Lincoln Centre Orchestra primarily to perform the trumpeter’s Symphony No 4 (The Jungle) with the Sydney and Melbourne symphony orchestras.

Marsalis says The Jungle is a musical portrait of New York City — the “most fluid, pressure-packed, and cosmopolitan metropolis the modern world has ever seen”. Marsalis points to the city’s many challenges — social and racial inequality, tribal prejudices, endemic corruption — and is concerned that “we may not be up to overcoming the challenges”.

Running at more than an hour and five minutes, and in six movements, the symphony is a substantial work. The opening movement, The Big Scream, is about dispossession. “It deals with the Native American spirit,” says Marsalis.

“Wherever you have native peoples who are displaced and conquered by people who have more technology, but with a Christian mandate, you have a scream.”

Displacement also exists in today’s world, he says. “You have people who are displaced when an expressway is built, people who can’t pay their rent, people who can’t keep up with the pace of the city. There’s a lot going on …”

Other themes explored in the five other movements — The Big Show, Lost in Sight, La Esquina, Us, and Struggle in the Digital Market — include city life and human relationships. The symphony explores various genres, including ragtime and Afro-Latin rhythms.

La Esquina, the fourth movement, means “hang spot”, and Marsalis says he is scoring many classic Latin rhythms here for the first time. “Latin music is an essential part of the American persona,” he says.

The musician says the five upcoming performances of The Jungle in Melbourne and Sydney will be invaluable. The work has had just a handful of performances since its world premiere in New York in December 2016, and the Australian tour will enable Marsalis to experience the symphony once again in the concert hall setting.

The trumpeter says he is mostly concerned that the sound of 80 musicians playing together is well-balanced.

• • •

Wynton Marsalis has been responsible for some of the most interesting controversies to energise the minds of jazz buffs for years. The mother of such dramas occurred in 1988, when he was executive consultant for the famous 19-hour Ken Burns documentary Jazz.

This was part of Burns’s trilogy on American culture, the other two having dealt with baseball and the American Civil War. The African-American experience was the common thread in each documentary.

The main bone of contention for many enthusiasts was that, in Jazz, the documentary marginalised many musicians who, after the 60s, in the opinion of Marsalis, had diminished the music by adopting rock rhythms, losing the essential sense of swing and, especially in the case of free jazz, removing the music from its roots in the blues. As Burns’s chief adviser, Marsalis took a lot of stick.

Now aged 57, Marsalis sounds very much like an elder statesman in relation to such historic issues.

“I seldom talk about those things now,” he says. “If you listen to The Jungle, you’ll see all those notes I put down. That’s what I think about now; I think about notes.”

Marsalis’s pre-eminence has largely enabled jazz to be brought in from the margins to a central position in American culture. There is perhaps no better example of the marginalisation of jazz than a notorious episode in 1965 when the Pulitzer board, despite the unanimous recommendation of its music panel, failed to award the Pulitzer Prize for Music to Duke Ellington, America’s foremost jazz composer of the 20th century.

Ellington was deeply hurt by the snub. Still, it took more than 30 years for this to be rectified when, in 1997, Marsalis himself became the first jazz composer to receive the Pulitzer for Music, for his oratorio Blood On The Fields.

Since that belated milestone, posthumous Pulitzers have now been awarded to Ellington, George Gershwin, Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane.

Marsalis’s CV includes pages of awards and he has been the recipient of 30 honorary doctorates from US academic institutions. Marsalis’s take on this is decidedly personal.

“I’m honoured by any award, but I think the award that I’m most proud of is just people who’ve come out, taken their time, brought their kids to hear us play, supported the music we play, invited me into their homes, cooked meals for me, and showed me unbelievable levels of respect. There’s been 40 years of it. I’m filled with an unbelievable humility and gratitude,” he says.

“The other reward I’ve had is to play with the level of unbelievable musicians I play with, and the type of dedication they show. We rehearsed today for four or five hours. We’ve been here a long time.

“Everywhere I turn it’s an unbelievable blessing. I’m truly grateful for it, and I try to let my work ethic, and the type of respect I treat people with, speak to that gratitude.”

Wynton Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Centre Orchestra commence their tour with four nights at Sydney Opera House from February 21, then go on to Melbourne and Brisbane.

by Eric Myers

Source: The Australian