Wynton Marsalis: how music makes a difference

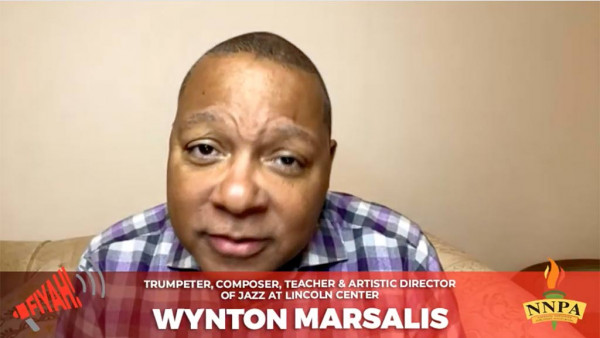

There is, unsurprisingly, no hint of lockdown sloppiness as the image of Wynton Marsalis appears on the screen of my laptop. The jazz maestro is noted for the sharpness of his appearance as well as his playing, and here he is wearing a suit and tie for our early evening conversation, sitting purposefully next to a piano. I say that the first time I saw his band at a London Jazz Festival concert, I was struck by the finely crafted tailoring on view, which seemed to make the music cleaner, tighter, more acutely directed than that of the groups that had preceded him.

“We were trying to do that,” he says. “Just trying to play, trying to be serious.” There was a time, he recalls, when the “fake liberal establishment were equating me with Ronald Reagan because I wanted to wear a suit. It was seen as some kind of subversive attack on the mythology of the ghetto.”

The unseemly scramble around the borders of the personal, the cultural and the political has been a feature of Marsalis’s long and distinguished career. He was born in New Orleans in 1961 in a house that was filled with music — his father was a jazz musician and teacher — and in a country still mired in explicit racism. “My trumpet teacher was from the north,” he says, “and he wasn’t as prejudiced as a lot of other people. But his wife did not want me to take lessons in their house.

“The fact that I had an afro and played classical music concertos was an issue. A white guy once gave me an album, because he saw my trumpet case, and he walked into the back of a streetcar where only blacks were [to give it to me]. That was the life we lived. I don’t really talk about it so much. People went through much worse stuff. But everything was tainted by that.”

Half a century later, those issues are still resounding across America, and Marsalis, Grammy and Pulitzer prize-winning trumpeter, composer and director of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, continues to address them in his work. An autumn tour with his septet is provocatively entitled “The Sound of Democracy”, while his new album, The Ever Fonky Lowdown, is a rambling and ambitious swipe at the material and spiritual corruption he sees around him, and the new wave of populism that promotes its pernicious spread.

The “lowdown” is guided by a narrator, Mr Game, voiced by The Wire’s Wendell Pierce, who is a satirically drawn amalgam of grifter, preacher, lawyer and businessman. “Mr Game is not Trump,” emphasises Marsalis, when I say it sounds like an album perfectly fitted for the present time. “He is anybody who is in that line, of bullshitting people. Take your pick: Julius Caesar, Adolf Hitler, even PT Barnum.”

The work’s rowdy and eclectic score, referencing the big-band sound of Marsalis’s native city and propelled by a Greek-style chorus of vocalists, is anything but uniformly sorrowful. But it does close with a plaintive chant, “I Know I Must Fight”, repeated solemnly over and over. “At a certain point you have to put your flag down,” says the composer. “And you have to do it wherever you stand, because the corruption is so great, so endemic to the human condition. We have to fight it in ourselves first. I made the decision not to make it about a particular battle, because all battles are important.”

For such a serious message, I say, people may be surprised by the album’s playfulness. Its very title is a double-double-entendre: a “lowdown” is a summary of important facts, also a way of describing immoral behaviour; “fonky/funky” describes a great sound, and a foul smell. It’s hardly a call to arms.

“No, but heavy injustice doesn’t always have heavy emotion around it. All those justices condemning these kids to prison, ruining their lives, they’re not going home with heavy hearts. Man, they are joking about it! Kurt Masur [the German conductor] was in Nazi Germany, a member of the military. He told me that there was a lot of cheerleading going on. The heavy emotion came at the end, with defeat.

“We tend to excuse that aspect of humanity which can be quite cruel, like kids in the playground, but which we then take to devastating consequence as adults.”

Marsalis recalls another incident from his childhood: an encounter with a nun who taught at his school, who he says cheated him out of a grade. “It was because she didn’t want a black person to be number one. I said to her after the last day of school, ‘I know I deserve the top award and you cheated me out of it.’ She said, ‘How do you know?’, and I said, ‘I do the cleaning after school and I looked at the grades.’

“She looked at me, and said, ‘Mmm, you shouldn’t have been looking at the grades!’ And I just had to laugh. There was something so funny about that, just me and her in the room. The irony of it!”

I ask about the latest tour: what exactly is the sound of democracy?

“Jazz,” he replies simply.

Just jazz? “Jazz,” he repeats. “You’ve got your individual rights — that’s improvisation. You’ve got your responsibility to the group — that’s swing. And you have your optimism and belief that your will and reasoning and choices can make a difference — that’s the blues.”

Can an art form really become a way of life, a moral code?

“My dad used to say, ‘Man, leave people alone, they have enough problems.’ The jazz code is very much live and let live, not sitting around judging other people. I remember talking to John Lewis [former musical director of the Modern Jazz Quartet], and complaining to him about all those generations of New York Times writers who were insistent on not taking our music seriously. And he said to me,” Marsalis picks the words out of his memory with deliberation: “ ‘Too much talking about criticism directed towards one is a form of egotism, just as much as bragging.’ ”

There is the sound of a mike drop from the annals of jazz history.

It has been said that jazz teaches you to listen, I say. “To listen, and to follow. Follow the line and anticipate. There is the pressure of time and harmony, a lot of pressure. And you have to be truthful because you don’t have time to get your lie together.”

He has said in the past that the blues were a kind of “secular optimism”, which was surely a stretch too far, even for someone of Marsalis’s engaging positivity? He turns to his piano, and begins to play some melancholy chords. “If you’re feeling bad,” he commentates, “it’s like this,” and he begins to moan: “_Whoah, whoah, it’s all right baby. Whoah, baby, it’s all right._” He repeats the phrase on each progression of the blues scale, until its final resolution.

“When you play the blues, what you say is sad: ‘You broke my heart baby, but it’s all right.’ But then it’s chump, chump, chump, chump,” he vocalises the chunky chords he is playing, “I’m coming back, I’m coming back. It’s the groove. The groove is the optimism.”

I’ll think about that on November 4, I say. “Let’s see what happens. We get to make a decision about who we want to be. And no one knows. Let’s see.”

‘The Ever Fonky Lowdown’ is out now on Blue Engine Records

By Peter Aspden

Source: Financial Times