Wynton Marsalis Gets Kind Of Blue

Thick in The South

There’s a recurring song on Wynton Marsalis’s formidable new trilogy, “Soul Gestures in Southern Blue,” called “So This Is Jazz, Huh?” It is both a challenge and a history lesson. Yeah, the song argues, this is jazz: a system of African-American mythmaking guided by the blues, with a rhythmic chain stretching back to pre-Civil War New Orleans and beyond. This is the seed for a grand musical discourse and an opening for unchecked pedantry. Over the almost three hours of “Soul Gestures in Southern Blue,” Marsalis gives both inclinations free play, to remarkable effect. As composer, arranger, musician and jazz ideologue, he has never been more impressive.

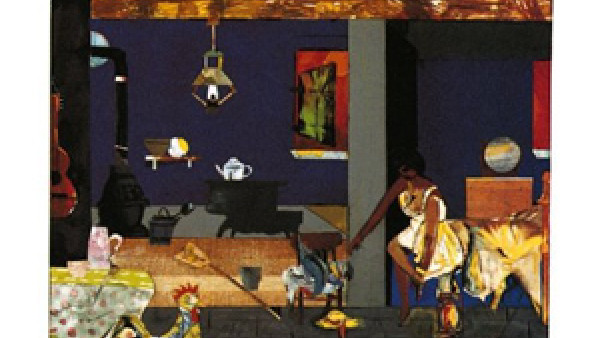

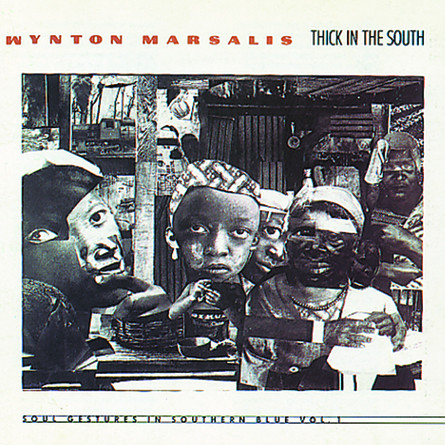

The package, recorded in 1987 and 1988, breaks down into three volumes, each available separately with its own Romare Bearden cover art (just in case you thought the pedagogy ended with the music). Each is a meditation on the blues; together, they form a blues cycle. These are slow blues, painstakingly arranged and played with almost obsessive clarity. Each volume tells a story that is equal parts geography and history. The first, “Thick in the South,” which features drummer Elvin Jones (who drove John Coltrane’s great ’60s quartet) and tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson, begins on the Underground Railroad, with an homage to Harriet Tubman, and ends in a chatter-filled barbershop. The second volume, “Uptown Ruler,” takes its name and flavor from a mythical New Orleans hero. Marsalis’s working quintet-featuring pianist Marcus Roberts, who now mostly leads his own group-maps the interplay of the blues with other New Orleans styles. “Levee Low Moan, “the third volume, adds alto saxophonist Wessell Anderson (a Marsalis regular) and plays with the different rhythms of the blues. It is the most sensuous of this very cerebral bunch.

But the cycle makes most sense taken as a whole. “Soul Gestures” derives some of its impact from pure heft. There’s never been such a deep, sustained modern study of the blues. Its scale lends it the majesty that sometimes eludes Marsalis and allows him to cut a romantic figure: the jazzman as keeper of knowledge, beholden more to study than to the often self-destructive conceit of a muse. Marsalis fleshed out this figure earlier this month as artistic director of the six-night classical-jazz concert series at New York’s Lincoln Center. Performing each night in a specific idiom (New Orleans, Kansas City, Ellington, Coltrane and jazz ,divas), surrounded by the masters of the idiom, Marsalis proved himself not just fluent in a daunting range of styles but able to articulate his own voice in each. He’s not really a conservative; he just has a massive vocabulary.

“Soul Gestures” runs up and down that vocabulary as Marsalis snatches blues rudiments and walks them through much of the span of jazz history. Though the set’s signposts are familiar-a little Ellington, some Coltrane and Miles Davis, plenty of Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver-it’s hard to say whose blues these are. They don’t do what the blues are traditionally supposed to do: there’s no feeling of spontaneous emotional outpouring. Everything, down to the most minute segments of the arrangements, feels under strict, deliberate control. This isn’t so much the blues as music about the blues.

Some people may find this abstraction maddening or too cold. But Marsalis isn’t after easy gratification. He’s after transcendent argument. And on “Soul Gestures in Southern Blue” he makes one.

by John Leland

Source: Newsweek